|

Second, many a young movie enthusiast first explores the terrain of classic and even contemporary cinema with the Oscars as a guide. If the Academy members voting for the Oscars had a clue, they'd be sure to highlight, for moviegoers present and future, Douglas McGrath's splendid adaptation of Nicholas Nickleby. The star of the British Queer as Folk, Charlie Hunnam, makes a smashing, sexy Nicholas - conveying both goodness and pride with every matinee-idol twinkle. There's an almost queer sensitivity he shares with Jamie Bell's abused, orphaned Smike, one of the most moving characterizations of the year. To contrast the virtuous, McGrath casts such actors as Christopher Plummer, Jim Broadbent, and Juliet Stevenson to give definitive portraits of Dickensian evil, always wrought with a sense of understanding for the squalor that deadens their hearts. Although necessarily shearing Dickens' novel, McGrath sustains the sprawling connections between Industrial Revolution horrors and character motivation, still spiked by Dickens' engrossing plot twists and coincidences. That social-economic narrative rigor - originating in Dickens' mass-produced serial style - allows McGrath to honor the development of lower-class culture as in the contrasting productions of "Romeo and Juliet", the paper dolls of the title sequence, and the traveling-troupe stylization of the movie itself. In addition, the extended family formed by Nicholas - as noted by Nathan Lane's drama-queen narration - links to the contemporary phenomenon of gay families. In adapting Dickens, McGrath recognizes the ongoing struggle to balance personal loss with perseverance.

No wonder a gay filmmaker as joyfully subversive a lover of pop culture as Pedro Almodovar seems to feel that in order to be taken seriously he also has to be dull. The use of modern dance in Talk to Her introduces the film's theme of male adoration and female subjugation. That and the (lame) silent film aside (featuring an incredibly shrinking man climbing inside of a giant vagina) reveal an artist no longer reveling in the hidden sexual codes within pop forms. The closest he gets are shots of dreamy Dario Grandinetti crying. However, even his tears are incited by conventional standards of "beauty," while Almodovar locates the source of his emotions in typical hetero anxiety.

Former Spielberg collaborator Menno Mejyes knows it. That's the almost-salvaging grace of his directorial debut, Max. Publicists courting Oscar voters started the rumor that the Weimar-era Max is supposed to "humanize" Adolf Hitler. As played by Noah Taylor, a humanized Hitler is surely not a monster, but a loud-mouthed, unlikable, pathetic, unimaginative, vulgar son-of-a-bitch (whodathunk?). Luckily, Taylor and John Cusack (as fictional art dealer Max Rothman) are in on Meyjes' elaborate joke. The conceit of Max is that Hitler's kitsch politics instigated the postmodern age. Meyjes uses the spectator's knowledge of what is to come to position every moment of the film, mixing low-brow humor (puns) with the modernist-era Expressionist visuals that connote the time (perhaps it holds the secret of history). Investigating the relationship of contemporary audiences to art and history, Meyjes settles on moral platitudes. Is it kitsch? "Modernism"? Or postmodernism? Who cares?

The much-misread final (credits) sequence is one of the most hypnotic screen moments: those hands, elaborating on the variants in the music, resonate with experience. It would be a shame if the Oscars (and history) deemed the life-sustaining ingenuity signified by Polanski's latest and McGrath's adaptation of Dickens to be insignificant. |

Charlie Hunnam as Nicholas and Jamie Bell in Nicholas Nickleby

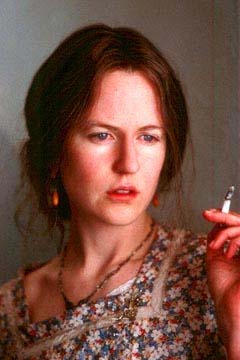

Charlie Hunnam as Nicholas and Jamie Bell in Nicholas Nickleby  Nicole Kidman likely will earn another Oscar nomination for her portrayal of Virginia Woolf in The Hours

Nicole Kidman likely will earn another Oscar nomination for her portrayal of Virginia Woolf in The Hours Oscar winners Nicolas Cage and Meryl Streep in Adaptation

Oscar winners Nicolas Cage and Meryl Streep in Adaptation  Adrien Brody is earning Oscar buzz for his role in The Pianist

Adrien Brody is earning Oscar buzz for his role in The Pianist