|

|

|

|

The Passion of the Christ |

|

In Braveheart, Gibson exploited homophobia by using the basest of cinematic techniques (mechanisms of suspense: anticipation and release). He whipped up excitement as Prince Edward II's male lover gets thrown out of a window by the King. It proved a divisive, post-Tarantino shock-tactic. The grossest kind of sentimentality, it won the film praise for its supposed old-school ("classic") entertainment. Now, Jivkov's emotional display in The Passion of the Christ puts the graphic violence of the film's representation of Passion-Play ritual in necessary context. Jivkov's beauty - and Gibson's presentation of it - makes the moment soulful. John's relationship to Mary and Magdalene conveys a shared need (established throughout the film as Gibson groups the three in compositions as they follow Christ's trials and the Stations of the Cross). That need is answered during Christ's sacrifice, offering this blessing from the cross: "Mother [Mary], behold your son [John]. Son [John], behold your mother [Mary]." The pleasure of beholding Jivkov's performance and screen presence mirrors the characters' recognized desire. With The Passion of the Christ, Gibson dares melodrama. "It is accomplished," Christ exclaims before finally perishing on the cross. His head bent upwards, covered in blood, he faces the camera, positioned in an overhead shot. Dead, Jesus' head sinks down (like Dali's rendition of the crucifixion). The overhead image rises to cgi heights as a digital teardrop falls from Heaven: causing the Earth to quake. In such representations, metaphor resonates with emotions. "The Passion of the Christ" offers a philosophical proposition of faith and religion: emotions - and the metaphors, signs that express them and the institutions that ritualize them (Gibson's Passion is in Aramaic and Latin) - validate a spiritual truth. The Passion of the Christ proves a surprisingly uncouth reversal of the bourgie-, hetero-hegemony propagated in such films as Paul Schrader-Martin Scorsese's dour, literalist Last Temptation of Christ (which continues to be acclaimed for emphasizing the "humanity" of Christ, thus erasing his signification of ultimate Difference, and for defining "humanity" in terms of temptation as hetero, bourgeois conformity and Satan as hegemonic emblem of innocence - a little white girl). The image of Jivkov crying (Gibson cites Caravaggio(!) as the inspiration for his the film's flesh-by-firelight lighting) registers spiritual intensity through the movie-based sensuality of his displayed sensitivity: and The New York Times quakes.

This basic, yet richly emotional, film technique gets complicated when Gibson replaces the literal point of view of Mary with a flashback. Jesus collapses under the weight of punishment and of the cross during the Stations of the Cross. Mary looks on with maternal terror and Gibson cuts to Jesus as a child, falling, followed by Mary (past and present) running to comfort him. Coming to the side of Jesus (in the "present"), Mary hears these words: "SEE, Mother, I make all things new." That is an intense proposition: the very terror/delight of existence. And its representation has always been bloody or violent - from the proto-Passion Greek Tragedy The Bacchae of Euripides to The Bacchae update of Brian De Palma's The Fury (and his entire oeuvre). For the faithful, its manifestation in reality was also violent - and liberating. The anxiety, as in Bosch's painting of Christ Carrying the Cross, is expressed in the ambivalent, mocking, shamed, or worried faces of the bystanders, both Roman and Jewish (who are whipped into hysteria by the Pharisees, themselves portrayed with looks of doubts aimed off-screen). Gibson addresses this anxiety and expresses this combination (violent liberation) in the image of Christ's bloodied body, nailed to the overturned cross, levitating - the film's divine culmination of the compassionate gestures - most notably Simon enlisted to help carry the cross - that mark the Stations. Furthermore, Gibson justifies consubstantiation (imagination as faith) and the ritual of Communion by splicing a flashback - within The Passion - to the Last Supper's bread/wine sacrament and Jesus' promise of eternal life. Gibson signifies this liberation through a rich system of associations and metaphors, as well as a certain pop panache. When Peter (Francesco De Vito) cuts off the ear of a Jewish guard, Jesus (his hand framed in the foreground with the guard's head, red blood complimented by the blue-lit Gethsemane background) restores the ear. After Christ's loaded warning: "He who lives by the sword, dies by the sword," Peter falls into the frame - a compositional thrill repeated when Jesus plummets into the shot, bound by chains, to foreshadow the hanging of Judas Iscariot (Luca Lionello). Gibson's symbol of Christ's ameliorating promise follows the temptation of Christ in the Garden by Satan. Satan tempts Jesus ("Who is your father? Who are you?") with the possibility of rejecting His fate. As played by an androgynous, hairless, pale-made-up actress Rosalinda Celentano (dubbed with voice of a man), Satan represents the possibility for Jesus to dismiss the pain of Difference (what separates angels from humans) rather than fulfill His destiny to suffer this pain for humanity. Later, in a mockery of The Virgin and Child, Satan coddles a demon child - a reflection of Christ's nature. At the end of the film, Satan's anguish is answered by a Pieta composition of Jesus' body in the arms of Mary (who is garbed in a nun's white-under-black hood). Awesome! (And I don't even have space to explicate Satan's derision of Christ's trials in the mini-Passion suffered by Judas.)

Within the limits of the twelve hours dramatized in The Passion (and the film's actual length), Gibson conflates the history - and the rituals and the systems formed from it - of Christianity and Catholicism. Anticipating Catholicism's development, the Roman Claudia Procles (Claudia Gerini), the wife of Pontius Pilate, shares her sympathy: offering a towel to Mary to clean up Jesus' blood or challenging her husband about his dismissal of "the truth" (as in Jesus' intention "To give testimony to the Truth"). That very Truth is the very spectacle of historical resonance, of emotional metaphors, of psychosexual symbolism, of cathartic ritual: providing movie signs with multivalent significance. "My God, why have you forsaken me?" is Jesus' primal scream on the cross. The terror of every moment - before it has meaning - is given meaning through Gibson's distillation of primal despair (the revelation of Difference) in the relationship between Mother, Son, and distant Father: that call brought back to basics. In response to that call, Gibson saves his most healing gesture, most audacious narrative risk, (and most controversial contention) for last, redefining all that came before. The last shot slowly moves through the space of the cave in which Christ is buried to finally reveal: the resurrected Christ, his body restored, has a hole in his hand. |

|

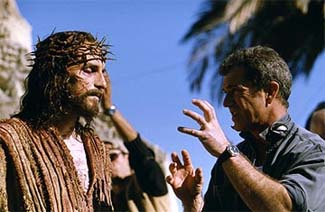

Mel Gibson directs James Vaviezel, who plays Jesus, in The Passion of the Christ

Mel Gibson directs James Vaviezel, who plays Jesus, in The Passion of the Christ  Mary (Maia Morgenstern) and Jesus (James Caviezel) in Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ

Mary (Maia Morgenstern) and Jesus (James Caviezel) in Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ  The Passion of the Christ has been criticized for its brutal violence

The Passion of the Christ has been criticized for its brutal violence