|

Film Review by John Demetry

Hill disrupts the shot-reverse-shot framing and editing with the wider shot of "Iceman"/Rhames exiting the showers. Glimpses of the other prisoners on the edges of the screen eventually bring the spectator's attention to a prisoner in the center of the middle plain. This movie extra, a Black man, looks directly into the camera and conceals his penis - his facial expression suggests shock/embarrassment at being exposed to the camera. That symbolic space and that spectacle of Black manhood have just been given human dimensions. However accidental this detail might be, it defines the spirited challenge of Hill's art and, especially, of Undisputed. Hill's "once upon a time in prison" isn't an example of Hollywood's fairy tales that glamorize social norms into a mythology. His cinematics perform a K.O. on such accepted myths. He takes myth's most exemplary power - to instruct in empathy - and turns it on its head. Hill frames much of the action through barriers - bars, cages, doorways, television screens - evoking the physical containment of characters, and the ideological (racial, gender, sexual) jail in which all of us are imprisoned. Characters are introduced with biographical stats, but Hill never reduces them to statistics. The transitions between scenes dissolve jail blueprints (hiphop-savvy Hill's reference to Jay-Z's masterpiece album "The Blueprint") over the regimented lives of the prisoners.

Yet, in the black and white (and red/read all over) world of criticism, this estimation of Hill and of Undisputed is, well, disputed. Most critics follow the lead of Miramax, which shelved the film for many months and has since claimed not to know how to properly market it. These critics reduce the film's significance to that of a failed or moderately successful genre film. The reader must recognize the ideological regimentation that critics and film distributors enforce: the layout of the ring and the stakes of the match. What pisses people off about Hill is his conviction that pop art can be - and should be and, in his hands, is - a site/sight of freedom. Hill calls for individual sovereignty. Thus, he receives the defensive responses of those who benefit from the system of "incarceration" - and, yes, by extension, real incarceration. The much disparaged, by film critics, climactic match between "Iceman" and Monroe superimposes the lives of the two boxers and the spectators with the forces that exploit and judge those lives. Radically, Hill replaces conventional - escapist - suspense with moral and social distress. This is why critics revile Hill: he finds that distress in the movie theatre. Shooting much of the match through the cage surrounding the ring, Hill pointedly relates the spectacle of Black men fighting each other with movies. He extends it to all media representations by introducing the fight with rapper Master P's rendition of the National Anthem and a series of dissolves showing prisoners joining in as a chorus. Hill constructs a polyrhythmic social vision with each percussive blow, syncopated edit, and graphically composed movement. The sequence is a masterpiece of expressive staging: so that the decisive left strike, composed at a diagonal, carries an emotional wallop. The final knockout, instant-replayed ala Hill in black-and-white, swings the match into a moral and philosophical abstraction.

These subtly performed and accented moments are, like every strike and counterstrike in the climactic match, the film's revelations. Hill and his actors dismantle masculine-racial ideology and media exploitation. The homophobic defensiveness, certified by celebrity, of the claim "Iceman" makes - "What have I got to rape someone for? I ain't no punk ass bitch" - crumbles in the expressive face of individual pain - and the actor's empathy. (Not insignificantly, this is Rhames' best performance and Snipes' best in years; displaying the talent squandered in racist Hollywood.) The final shot is one of the most complicated screen moments of recent memory. Snipes'/Monroe's Zen dispassion breaks into a cocky smile as the prisoners pronounce him as their champion. The black-and-white image concludes with the sides of the screen closing in on him. Only by resolving that image's conflicted significance will the audience be free. |

|

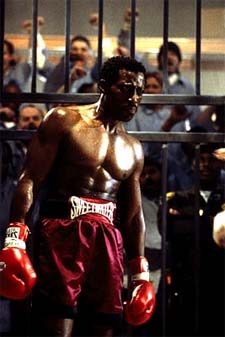

"Iceman" (Ving Rhames) and Monroe (Wesely Snipes) vie to be undisputed champion in prison

"Iceman" (Ving Rhames) and Monroe (Wesely Snipes) vie to be undisputed champion in prison  Mendy Ripstein (Peter Falk) masterminds the prison fight with "Iceman" (Rhames)

Mendy Ripstein (Peter Falk) masterminds the prison fight with "Iceman" (Rhames)  The look on Snipes' face, before raising his hand in victory, is

devastating. Unlike the extra covering himself in the shower, Snipes and

Rhames openly display their (emotional) prowess. In one slow-motion shot,

framed by the doorway of solitary confinement, Snipes stares into the

camera, baring the weight of the murder of Monroe's woman's lover. In

another dramatic highpoint, Rhames, frustrated, says, "I'm trying to explain

to him how to survive," then wearily lifts his handcuffed fists.

The look on Snipes' face, before raising his hand in victory, is

devastating. Unlike the extra covering himself in the shower, Snipes and

Rhames openly display their (emotional) prowess. In one slow-motion shot,

framed by the doorway of solitary confinement, Snipes stares into the

camera, baring the weight of the murder of Monroe's woman's lover. In

another dramatic highpoint, Rhames, frustrated, says, "I'm trying to explain

to him how to survive," then wearily lifts his handcuffed fists.