|

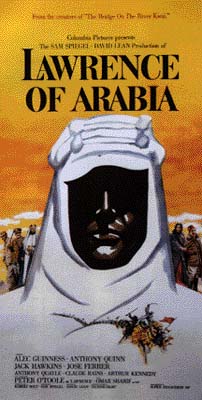

Film Review By John Demetry

"What? More words?" says an attendant at T.E. Lawrence's funeral to a

reporter covering the event at the beginning of David Lean's Lawrence of

Arabia. Lean knew that words alone could not tell this story and explore

his considerable themes. Do not miss the restored 70mm theatrical re-release

of the 1962 Lawrence of Arabia. It's your chance to experience the most

ravishing 70mm images ever to hit the screen.

"What? More words?" says an attendant at T.E. Lawrence's funeral to a

reporter covering the event at the beginning of David Lean's Lawrence of

Arabia. Lean knew that words alone could not tell this story and explore

his considerable themes. Do not miss the restored 70mm theatrical re-release

of the 1962 Lawrence of Arabia. It's your chance to experience the most

ravishing 70mm images ever to hit the screen.

Lean takes full advantage of film's ability to multiply the ecstatic potential of signs by speed. At four hours, Lawrence seems fleet because every shot, cut, and transition constitutes an emotionally, sexually, psychologically, politically, and metaphysically imaginative perception of history and the meeting of Western Imperialism and Middle Eastern culture. The spectator needs four hours and Lean's meditative compositions to take it all in - ideas, illuminated. Lean's artistic, idiosyncratic take on history matches the quixotic, conflicted persona of T.E. Lawrence and the mercurial, star-making performance of Peter O'Toole. O'Toole's every inflection and gesture conveys the coiled aggression and compassion of Lawrence's egomania; he wants the Arab people to be free, but it's a freedom he must give them. Wielding a gun to enact judgement on the Arab whose life he earlier saved, Lawrence's body nearly combusts with terror and pleasure. It's Lawrence's first killing, wrought with the moral tension that will later climax with the harrowing, horrifying "No Prisoners!" slaughter. Lawrence struts with the matinee-idol confidence of sexual conquest on top of a fallen Turk train, posing for photographs and for the adoration of his followers. Lean and O'Toole so fully immerse themselves in Lawrence and HIStory, they come out of the desert of Lawrence's delusion - complete with sand twister as column of fire - with new understanding.

Lean cuts from Lawrence extinguishing a match at the British headquarters in Cairo to the sun rising over the desert expanse. It's a graphic match of a match - an awe-inspiring introduction to Lean's poetics of scale and mise-en-scene: man and land, individual and history. Lean is an erotic visionary: as when two riders on camels pass each other like lovers in the overwhelming horizontal span of the Sun's Anvil. A self-identified visionary, Lawrence proclaims: "Nothing is written." Embarking on a rescue mission to the Sun's Anvil, he boasts of his inevitable success, "That is written. In here," pointing to his head. Finally leaving the Arabian campaign to Prince Feisal and British politicians, a motor bike passes Lawrence, bringing the film full circle as a premonition of his unspectacular death. Like the 70mm image that doubles the resolution of the usual 35mm film, so Lean enriches the concept of destiny and the social cross-section probably inspired by Charles Dickens. In his adaptation of Dickens' Oliver Twist, Lean cast Alec Guinness as Fagan - with his grotesque puddy nose, an intentionally twisted projection of anti-Semitism. Guinness' chameleon skills have never been more profoundly utilized than as Prince Feisal in Lawrence.

Lean proves himself a King by radically elucidating the racial and sexual implications of Lawrence's story. Codes of manhood - military, British, Arab, Turkish - are constantly undercut by the film's homo-eroticism and open gallery of male emotions. Sherif Ali Ibn El Omar (played by a dashing Omar Sharif) cries over the dissolution of the independent Arab government. Lawrence takes two Arab boys under his wing. "They're not servants. They are worshippers" - an erotic, racially-loaded bond. Lawrence leads each boy to his demise - each played like a lover's death scene in a melodrama. Lawrence, himself, is tortured and raped by the sadistic Turk played by Jose Ferrer - the objectification that finally burns Lawrence ("The trick is not minding that it hurts"). In the desert, Lawrence meditates on the decisive attack on Aqaba. Lean turns the sequence into a series of erotic dissolves: the sun, the dunes, the wind. The Arab boys who serve Lawrence throw a rock down a dune, hitting the small of Lawrence's back. Under a desert tree with the boys, Lawrence is struck by a boldly sexual inspiration: take Aqaba from behind. The long tracking shot that documents the attack on Aqaba provides the orgasm, ending with a cannon in the foreground erected towards the sea. This desert is hot! But it's a heat that burns. Through Lean's vast, humane vision, we, the audience, discover the heart of darkness in Lawrence - and in ourselves. |

|

Peter O'Toole as T.E. Lawrence with Anthony Quinn as Auda abu Tayi

Peter O'Toole as T.E. Lawrence with Anthony Quinn as Auda abu Tayi  Alec Guinness plays Prince Feisal in David Lean's Best Picture film Lawrence of Arabia

Alec Guinness plays Prince Feisal in David Lean's Best Picture film Lawrence of Arabia