|

|

|

|

|

By John Demetry

"At heart, the best action films are slicing journeys into the lower depths

of American life: dregs, outcasts, lonely hard wanderers caught in a

buzzsaw of niggardly, intricate, devious movement."

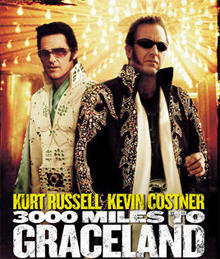

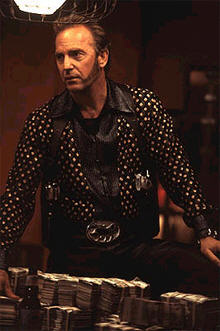

They'll toss aside the film with a few niggling remarks about "plot holes," behind-the-scenes ego battles over final cut between stars Kurt Russell and Kevin Costner, both of whom will then be the targets of old fart jokes. They'll reserve their gaseous hot air for White-Elephants-in-Termite-drag like Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and Traffic. Like the film or not (and I do like it plenty), the readers of film criticism and the audience for movies deserve insight and honesty from their critics. The awful truth: 3000 Miles to Graceland is a better, richer, wilder, rougher (and thus a more interesting) film than any nominated for the Best Picture Oscar this year. Letting it slip through the cracks of popular consideration, critics (www.dvexpress.com's Gregory Solman and www.nypress.com 's Armond White excepted) give it the burrowing, undetected vitality of Termite Art. Recalling the precedence of Farber is as humble, and rare, as director Demian Lichtenstein's drawing upon his filmic obsessions. From Walter "da bomb" Hill to Oliver Stone to Sam Peckinpah, he finds the often-exhilarating (sometimes exhausting) cinematic language to delve deep, winding paths into the American male mythos and reality - which was the beloved beneath-the-surface theme of Farber's “Underground Films”. Lichtenstein's satirical speed catches American machismo's impulsive, pathetic bravado on the run. He nails it with a low-angle shot of Costner in Elvis garb before executing a casino heist (with a gang of Elvis impersonators). It's modern perspectives examined with film style: which basically describes the awesome spectacle of the heist.

An early stylistic climax, it sets up the complexes that detail the drama of the rest of the film. Critics, like those who thought the danger was supposed to be on Mars in Mission to Mars because that's what previews told them, must have been thrown into a stupefied tizzy indicative of the dumb-ass morass that swamps our culture. Keep alert: Lichtenstein helps navigate through the swamp. He pits the weathered movie-star iconography of Russell and Costner against each other in unexpected ways. The film opens with a computer-animated homage to the beginning of Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch with a black scorpion and a white scorpion doing battle. Lichtenstein also goofs on genre shorthand - ala Hill as in his 1984 masterpiece Streets of Fire, which by deepening music video aesthetics must implicitly, if not explicitly, influence music video director Lichtenstein. Russell's always been a keen satirist-and-sympathizer of American ambitions. You can't forget his endearing "Trust me" sliminess as the salesman in Used Cars nor his part-sincere, part-spoofing Libertarian ubermensch Snake Plisken in John Carpenter's "Escape from." movies. He effortlessly engenders audience identification but flips it into a challenge. Here, his challenge is his own: how to use his screen presence to connect (with audiences, with his love interest and her son). The genuine warmth he exudes here expresses moral intuitiveness. That explains Russell's expressions of thoughtful horror as the heist turns into a massacre. (It's not unlike his expression when he caresses Courtney Cox's hair before leaving her an attempt at a romantic present: a Snicker's bar. Or, later, when Russell holds Cox in his arms after she realizes how her greed and double-dealing has put her son in danger.) And then, Lichtenstein maximizes the space in the escape helicopter, using depth of field to reveal Russell's intense ruminations on Costner's distress after failing to save a bullet-riddled cohort.

Further complicating the Costner persona, 3000 Miles historically pinpoints his character's psychology. After being a medic in Vietnam, Costner became obsessed with proving that he is the illegitimate son of The King. So, in the film's narrative, he begins a destruction orgy across the U.S.A. after the heist. All the way flashing his superstar charisma like a moral blank check. Paralleling Russell and Costner's quests for the laundered money at the end of the rainbow, Lichtenstein contrasts two American roads to excess. The "niggardly, intricate, devious movement" of these two "dregs, outcasts, lonely hard wanderers" fulfills Farber's criteria by combining new, hip technique with immanently modern concerns. Lichtenstein achieves this through a post-modernism that takes us beyond Farber's era. Costner's final grace note: he shoots his reflection in a mirror. Russell's: he takes off in his father's boat (named Graceland), bringing Cox and her son with him. It's another homage to Peckinpah. The ending of Peckinpah's Killer Elite, in which the hero and his last trusted friend sailed into the sunset of personal oblivion, was famously read by Pauline Kael as evidence of Peckinpah's escape from Hollywood. Lichtenstein reinterprets the image as the healing of the American male psyche. Russell begins the search for a new land of grace. |

© 1997-2002 BEI

It's hard to guess whether the Farber of 1957 (or of 2001) would rank 3000

Miles to Graceland as one of the best action films. But it's scary to think

that most critics wouldn't even consider the challenge to place 3000 Miles

within a defining critical aesthetic of their own, much less Farber's.

It's hard to guess whether the Farber of 1957 (or of 2001) would rank 3000

Miles to Graceland as one of the best action films. But it's scary to think

that most critics wouldn't even consider the challenge to place 3000 Miles

within a defining critical aesthetic of their own, much less Farber's.

Kevin Costner's diversity of on-screen personalities grows in 3000 Miles to Graceland

Kevin Costner's diversity of on-screen personalities grows in 3000 Miles to Graceland