|

|

|

|

|

Film Review by John Demetry

Lola is at the center of an enlarged romantic la ronde set in Demy's own hometown of Nantes. Lola keeps her heart closed. She has an affair with an American sailor, Frankie (Alan Scott), on leave in Nantes. Frankie's moony sailor reminds her of both her true love and a childhood admirer, Roland (a sexy, yet not romanticized, rebel without a cause as played by Marc Michel). Frankie begins a flirtation with a 14-year-old girl named Cecile (the alarmingly hot Annie Duperoux). Cecile's mother, Mrs. Desnoyers (Elina Labourdette), attempts to ease her loneliness after her husband's death by trying to seduce Roland. Roland humors her because Cecile reminds him of that long ago Lola. At first, the spin of this roundelay feels pleasurably simple. When Lola and Roland finally meet again, however, it becomes increasingly - deliriously - complicated. The unraveling of Lola oscillates between the unexpected and the inevitable. Each of these overlapping love stories retells different stages of the Michel-Lola-Roland love triangle. Crossing between three generations, Demy's art remains open to all possibilities. Through it all, Michel could be a mysterious man driving through Nantes in a white Cadillac. Thinking it might be Michel's car, his mother describes it as "a gorgeous car out of a dream."

Demy's dramatization of this modern existential dilemma is, well, dreamy. After seeing a Hollywood film, Roland announces: "It's always beautiful in the movies." "And in life!" reminds Michel's mother, unsatisfied that the sky and the ocean blend in her painting. Demy makes the conundrum of American pop fantasy's pull on the imagination easily understood. It's a dilemma played out in terms recognizable to anyone who has ever fallen in love. That's no simplification. Demy explores romantic love in radical personal, social, and historical terms. Demy's filmmaking answers Roland's self-defining terror: "I have no work to create. I am lost!" Demy's musical omniscience - the all-knowing as all-loving - challenges the audience to not get lost. He mixes the conventions of Hollywood musicals and the riches of French melodramas by Max Ophuls (to whom the film is dedicated) with the aesthetic and moral imperatives of the French New Wave. The jazz-impulse cinema of Demy enriches and emboldens the narrative variations. Collaborating with master cinematographer Raoul Coutard, Demy transforms the location shoot and the natural light into a magical realm. Coutard's Cinemascope black-and-white photography attunes viewers to the philosophy of forms, to Demy's delicate choreography. Characters constantly cross paths. Coutard's camera dances with performers and architecture, isolating each devastating revelation. Roland, in a dark suit, walks away from the camera into the streetlight-illuminated abyss of self-delusion. Frankie, in his white sailor uniform, walks toward the camera - doing a little dance kick as he passes Roland. Every image in Lola has the graphic excitement of life heightened to emotional cross-purposes. There are moments in Lola when the audience experiences about ten different emotions at once. The spectators of Lola are like the showgirls at the end, crying over a romantic reunion then announcing: "Let's have some fun!" Michel Legrand's music amplifies this sense of life. In the best jazz sense, Legrand's score consistently startles. At the beginning, it erupts then pauses - the lyricism continued by editors Anne-Marie Cotret and Monique Teisseire's dissolves. Then, the shutting of a car door cues the score to commence - at full blast and full speed. The music cues intensity. Legrand swings when Roland announces: "One day, I'll leave." It's a foreboding of the continuation of Roland's story in the all-singing classic, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg - Demy's ambiguous, melancholy riff on Lola. All of these elements achieve a sublime expressive unity in the scene of young Cecile and the sailor Frankie at the fair. Placing his camera on a bumper car and a carousel, Demy captures the rocky exhilaration of adolescent first love. Cecile lets her hair down. Frankie puts his arm around her shoulders. The slow-motion departure from the carousel achieves genuine ecstasy. Here, Demy lingers on the quintessential existential moment of all the characters' lives. Cinematic pleasure and ideas resonate with emotional bliss and anguish.

In a 1961 interview, Demy said of Lola: "I would hope that anyone feeling depressed or glum, who goes to see Lola, leaves with a smile on their face and that the film manages to change their state of mind and outlook on life -- at least temporarily." Demy knew it: Once is not enough! Lola is a movie to be seen -- then lived. |

© 1997-2002 BEI

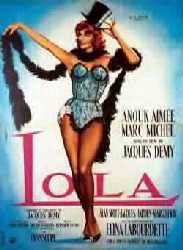

Anouk Aimée perfectly plays Lola, a mother turned cabaret performer

Anouk Aimée perfectly plays Lola, a mother turned cabaret performer  The dreams of the denizens of Demy's

Nantes inscribe a vision of the world as one of individual fantasies and

philosophies in ceaseless metamorphosis. Each intersecting line of fate and

faith challenges the characters - and the audience.

The dreams of the denizens of Demy's

Nantes inscribe a vision of the world as one of individual fantasies and

philosophies in ceaseless metamorphosis. Each intersecting line of fate and

faith challenges the characters - and the audience.