|

|

|

and the Voices of Revolution |

|

Interview by Jack Nichols

Dr. Streitmatter's previous works include: Raising Her Voice: African American Women Journalists Who Changed History; Unspeakable: The Rise of the Gay and Lesbian Press in America and Mightier Than the Sword: How the News Media Have Shaped American History. Jack Nichols: You've made a clear distinction between what we generally call the alternative press and what you are now calling the dissident press. Would you explain this distinction? Rodger Streitmatter: Many American cities now have weekly tabloids that offer sort of a more "hip" view of the world. The Village Voice in New York and the City Paper here in Washington, D.C., come to mind. They look at the world from a different view than, say, the New York Times or Washington Post, but they don't fit my definition of being dissident because they aren't really trying to change society in any fundamental way. For a publication to merit the mantle of "dissident," at least in my book, it not only had to offer a differing view of society but also had to seek to change the world -- to champion a particular cause.

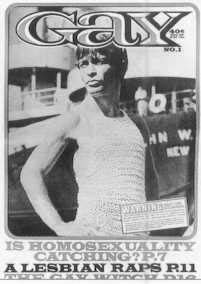

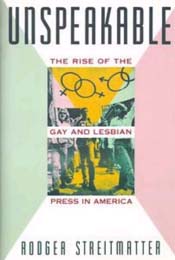

Then I came along and wrote my 400-page history of the gay and lesbian press a few years ago, partly to show my fellow media scholars, as well as other people, that there has been, for many years, a very vital and substantive journalistic genre aimed at gay people. Now, when writing Voices of Revolution, one of my goals was to make it easy for media historians to incorporate the gay press into their classes. My hope is that professors will use this book in the classroom and thereby introduce their students to the gay press because there's a chapter on it. The professors won't have to do their own research, which many of them would be very uncomfortable doing. It's all right here in front of them to read, right along with their students. Jack Nichols: Although you ably covered the history of The Advocate in your book Unspeakable, you've made no mention of that newsmagazine in Voices of Revolution. Why? Does it have something to do with its editorial slant? Rodger Streitmatter: The Advocate has gone through numerous phases since it was founded in 1967. During many of those stages, it has served a valuable purpose. But during the years immediately after Stonewall, which is the period I focus on in the chapter on the gay press in Voices of Revolution, The Advocate was awfully tepid, both editorially and in its appearance and general tone, compared to some of the other wonderfully vibrant and colorful papers -- like GAY, Killer Dyke, and Come Out! In my opinion, those "wild and wooly" papers captured the essence of the era much better than The Advocate did. Jack Nichols: Why did America's first gay weekly, GAY, appeal to you as a dissident publication? Its early gay Marxist critics were, as I recall, appalled by its combining of features, news and nudity.

Here was a paper that had the nerve to actually reflect and celebrate the values of the subculture it was serving, not to limit itself to the dictates of the larger culture. So, in its own way, GAY was saying what other activists would be saying twenty years later: "We're here, we're queer, get used to it!" Jack Nichols: Last week I wrote a GayToday Viewpoint feature titled "The Big Republican Lie about a Liberal Media". In it I complained that the mainstream media seems hamstrung by the influence of major corporate powers. Am I right to worry about the possibility of corporate censorship because of such matters? Rodger Streitmatter: It's a serious concern. I worked as a mainstream newspaper reporter and editor for a number of years back in the late '70s, before I started teaching. Back then, reporters could write about almost any topic we wanted to; we knew our publisher didn't like us to say anything bad about Presbyterians, but other that that, most anything was fair game. That has changed. With Disney owning ABC, for example, the corporate office now has a huge say in what ends up on the air. The news media that used to be a "watchdog" over the government and corporate America is now much more of a docile little "puppy dog."

Rodger Streitmatter: I think so. I've already had several classes read the manuscript in draft form -- it's great to get student feedback -- and dozens of students have told me they found many of the people in the book to be quite inspirational. And several of those students have said they now intend to work for dissident publications. The conventional wisdom is that today's students are apathetic or total slackers, but I don't agree. Most of them are eager to commit their energy and their creative talents to worthy causes -- but they have to find something they care about. Jack Nichols: I notice that you've asked for understanding and appreciation of badly misunderstood causes such as anarchism and socialism. What are some of the reasons you feel this way? Rodger Streitmatter: I remember a couple summers ago when I was working on the chapter on the socialist press and my sister and her husband from Illinois came to visit me in my home in Washington, D.C. When I told my brother-in-law what I was writing about, he scowled and asked why I would waste my time writing about some terrible thing like socialism -- barely able to say the word. Gene is a former Marine who moves mobile homes for a living. He's a nice guy and I like him, but he's typical of many people in Middle America who feel a chill run up their spine when they hear words like "socialism" and "anarchism" -- without really understanding what those concepts mean. A socialist believes that the government should intervene on behalf of the working class and that laborers who produce goods should benefit from their efforts. Is that such a radical notion? And an anarchist, as I see it, believes in the supremacy of individual liberty, which is exactly what the men who founded this nation believed in, and also is concerned that capitalism has become the defining force in this country. Again, those ideas don't sound so radical to me. So part of my agenda in writing about some of these dissident presses was to help students get a better understanding of some of these concepts that so many people don't really know much about. Jack Nichols: Your treatment of the African-American community publications that got their starts in the early years of the Republic reveals how America's dissident anti-racist press evolved. What have been principal issues that have slowly but surely emerged in that press?

Jack Nichols: What have been some of the principal gay and lesbian issues? Rodger Streitmatter: My chapter on the gay press looked specifically at 1969 to 1972, the period immediately after the Stonewall Rebellion. Some of the issues that the papers debated were resolved during those three years. For example, it became clear, because of both the editorial and the graphic content of the papers, that gays would not try to emulate the sexual mores of straight America but would develop their own set of values in this regard. But, curiously, several other issues that were hot topics then are still being debated thirty years later. One example is whether drag queens and dykes on bikes should be celebrated as a colorful part of our community or be nudged to the margins; I still hear people arguing that point today. Another unresolved issue that has been around since the late '60s is which of the many reform efforts should be fought first -- whether it's more important, for example, to put our efforts into electing gay and lesbian candidates to office or to fight for legal rights such as same-sex marriage. Jack Nichols: How has your voluminous research into America's dissident press affected your own journalistic outlook?

Jack Nichols: Your chapter about the counterculture uprising of the late 1960s is followed by a chapter on the black struggle and then by the gay and lesbian press. Do you sense that the influences of the late 1960s counterculture movement and the black civil rights movement-and, certainly, feminism, proved somehow influential in gay and lesbian liberation circles? Rodger Streitmatter: There's no question that the Counterculture Movement helped lay the groundwork for gay people to demand equal rights. Race, gender, class, personal freedom, self-expression, the nature of consciousness -- they were all on the table in the late 1960s when this huge bulge of young adults, a lot of us born right after World War II, began questioning conventional thinking in so many areas. Of course the most significant step came when young people started moving toward more liberated attitudes toward sex and gender roles. After that, it was really only a small step to celebrating male-male and female-female sexual activity. Then again, as a historian looking back on that period, I can claim 20/20 vision. In fact, it wasn't really a "small" step at all -- it was an enormous step, as well as a courageous one, considering the cultural restrictions at the time. Jack Nichols: What perspectives from the Free Love movement of the 19th century might be applied, possibly, to gay and lesbian lovers today? Rodger Streitmatter: The central concern of the 19th century free lovers was that too many people were trapped, by the conventions of society, in marriages that were definitely loveless, and often abusive. What these rebels wanted was for women and men to be free to divorce, according to the ebb and flow of their love for each other. This concept of re-examining conventional marriage certainly has relevance to lesbians and gay men today. Civil unions and gay marriages come immediately to mind, of course. But I think we also all know of gay people who have created their own successful relationships that are outside the parameters of the man/woman/death-do-us-part conventional marriage -- couples who love each other but choose not to live together, groups of three or more people who are much more committed to each other's well-being than many husbands and wives are. Jack Nichols: Rush Limbaugh and his GOP cronies have been attempting to denigrate the principle of the equality of the sexes for over a decade. Do you think that the propaganda spewed by these conservative zealots has been particularly successful at stirring up public antagonism to equal rights for women? Rodger Streitmatter: I'm amazed at the number of people I encounter, many of them female students, who like to make it very clear that they are not feminists. I find it appalling. All that being a feminist means, as I see it, is believing that women should have the right to pursue any vocation or activity that men can pursue -- and that they should be compensated equally for any success they have in that pursuit. Frankly, I can't understand how anyone could possibly NOT believe that. Personally, I think Rush Limbaugh and other right-wing conservatives -- not all conservatives but the ones on the far right-have had a lot to do with "feminist" becoming a poisonous word. Limbaugh coined the word "femi-Nazi," and then somehow managed to convince a lot of people that women have gone too far. The average American woman is making only 72 cents for every dollar that the average man makes, so I hardly think they've gone too far.

As for Emma Goldman, what really stands out about her, in my mind, is how she believed so strongly in certain ideas that she wouldn't back down -- not a single inch. Even after the government put her in jail for a year, while she was still a young woman, and then later declared her "the most dangerous woman in America" and later still deported her, she held true to her beliefs throughout her entire life. Emma Goldman failed to change society, as most people still opposed anarchy, but, nevertheless, she remained true to her beliefs. So, on a personal level, she did succeed. Again, what an inspiration! Jack Nichols: Which other crusading journalists have been among your favorite historic characters and why? Rodger Streitmatter: I'd have to add Ida B. Wells to the list. She founded the anti-lynching press in the late 19th century. So here we have this African-American woman who was born into slavery in Mississippi during the Civil War. And then in the early 1890s, when she was still in her twenties, she has the audacity not just to enter the field of journalism, a bastion of white men, but to use the press to expose the fact -- for the first time-that this whole idea of black men being lynched because they were raping white women was a total and complete fabrication. White southerners forced her into exile in the North and swore that if she dared to come back to the South she'd be hanged. So she continued her crusade in New York, carrying a loaded pistol in her purse all the while. Wells virtually single-handedly told the whole country, as well as England, about the brutal realities of lynching, something that people in the North had no idea was happening. That she succeeded, with the impediments she faced, is absolutely extraordinary. Jack Nichols: You told me earlier that you feel much satisfied after having written Voices of Revolution. You've already written three previous books on the media. Tell us what, in particular, has made you feel this way about Voices of Revolution? Rodger Streitmatter: My son, Matt, is 26 years old. He's a great kid, very kind and very generous, but he always had a hard time with school. Several years ago, he was taking a community college course in American history and was having a really tough time, so I was working with him. And I still remember this one time when he read a chapter from his textbook and then I asked him what was the most important point of the chapter, and he just sort of sat there and looked at me. I knew he'd read every single word in that chapter, but those twenty or thirty pages were so dry and boring, filled with so many names and dates -- it was deadly. What I am so proud of regarding Voices of Revolution is that it is readable. In fact, it's not just readable -- it's compelling. The remarkable men and women in this book and the social movements they led are so powerful and so engaging that they show young readers what a joy learning history can be. Jack Nichols: Thank you from the bottom of my heart, Rodger. You've not only written the definitive history of the gay and lesbian press, Unspeakable, but now -- in your Voices of Revolution ---you've managed to incorporate our press into the story of America's journalistic development. That's no small accomplishment and it makes you, I say, as much a contributing activist as any of the women and men you've honored so beautifully in your writings. |

© 1997-2002 BEI

Rodger Streitmatter, Ph.D.,

author of Voices of Revolution: The Dissident Press in America,

is Professor of Journalism at American University,

Washington, D.C.

Rodger Streitmatter, Ph.D.,

author of Voices of Revolution: The Dissident Press in America,

is Professor of Journalism at American University,

Washington, D.C.  Voices of Revolution is the first history textbook

about America's dissident press that includes

the gay and lesbian press.

Voices of Revolution is the first history textbook

about America's dissident press that includes

the gay and lesbian press.

GAY: '(F)its perfectly with my concept of a paper that was trying to change society -- as well as change journalism.'

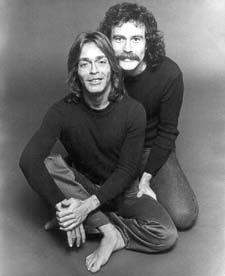

GAY: '(F)its perfectly with my concept of a paper that was trying to change society -- as well as change journalism.' The Editors of GAY, Lige Clarke & Jack Nichols as shown

in Rodger Streitmatter's new history, Voices of Revolution

The Editors of GAY, Lige Clarke & Jack Nichols as shown

in Rodger Streitmatter's new history, Voices of Revolution  Unspeakable is Dr. Streitmatter's 400-page history

of the gay and lesbian press, published by Faber & Faber

in 1995

Unspeakable is Dr. Streitmatter's 400-page history

of the gay and lesbian press, published by Faber & Faber

in 1995  Emma Goldman, the famed anarchist journalist, was,

among other things, gay-friendly. Authorities considered her

'The most dangerous woman in America'. She was imprisoned because

of her views and then deported.

Emma Goldman, the famed anarchist journalist, was,

among other things, gay-friendly. Authorities considered her

'The most dangerous woman in America'. She was imprisoned because

of her views and then deported.