|

|

|

Interview by Jack Nichols

When I first met John R. Stowe, the author of Gay Spirit Warrior , I noticed how he seemed always to be in good spirits, keeping himself busy, humming happily, learning about the world around him and, as a young man, deciding with care which attitudes would best lead to greater satisfactions in daily living. Many people mistakenly think spiritual work is all about discipline and denials of material life. In too many spiritual traditions there are dour prejudices against fun, against sex, against anything sensual or physical. In John's new book (published this month) he implies that spiritual empowerment can be both fun and sexy. And I observe, in his own life John has simultaneously embodied the advice of The Buddha: "Work out your own salvation with diligence." John continues today to be lover of trees and flowers, a baker of cookies and cakes, a cheerful, healthy presence eager to give life's better gifts to his friends and acquaintances. This concern for basics-such as proper diet--and a willingness, even at his own expense, to upgrade conditions for his fellows, manifested during his visit to my home in the mid-1980s. John was worried, he told me, about the quality of the pots and pans in my kitchen, a variety he feared could, because of their "cheap" makeup, prove somewhat poisonous.

Traveling far and wide outside the United States, handsome John set out to discover his own spiritual path. He was growing up--finding and practicing effective approaches to daily living. He was not a follower, it was clear, but a leader. John became a founding member of Gay Spirit Visions, a spiritual odyssey group based in the Atlanta area. His influence in this worthy group has since been profound, while its membership has evolved into a genuine community of friendly, happy-go-lucky, sharing souls.

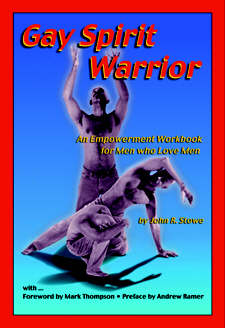

John R. Stowe: Gay Spirit Visions was founded in 1990 by 3 friends of mine as a conference where gay men could explore what it means to be gay and on a spiritual path. Over our ten years together, it's grown into a sort of extended family of men sharing mutual love and support. Our interaction is really more like co-mentoring, where each participant contributes his own insights to the deepening exploration. It continues to evolve as we focus on different areas of concern -- things like healing, internalized homophobia, mentoring, creativity, living in the world with integrity, and celebrating the wonder of our own beings. Because we're all learning from each other, there always seem to be new insights. Even though we all approach the process with different questions, it seems that most of the time we get what we need. And none of us, I think, ever outgrows the need for a circle of deeply supportive gay friends. Jack Nichols: Why did you write your latest book, Gay Spirit Warrior ? What does it add that your earlier books didn't address? John R. Stowe: The book grew out of a personal realization that after 20 years of being out -- including at least 15 of those helping other gay men their full potential -- there were still things I wanted to do in my life that I was afraid to approach because I was gay. Looking around, I realized I wasn't alone. Gay people carry tremendous healing, vitality, passion, and creativity. We have the potential to make unique and important contributions to the world, that in fact are needed quite desperately. And yet, even though many individuals are doing important work, as a community I don't see us living up to our potential. Almost all of us still carry negative baggage from growing up in a homophobic world. The negativity can be dramatic, but most often it comes through more subtly, as hidden fears or doubts that sabotage various aspects of our lives -- from relationships, to careers, to happiness. So the book was both a personal exploration and a way to help others move beyond wounding toward a much deeper sense of satisfaction and freedom. Jack Nichols: You often remind friends and your readers to pay less attention to what others think of them and more attention to what they think of themselves. What others think, you say, is "just theory until we go inside ourselves, discover who really lives there, and then come out into the world on our own terms -- not just as part of the gay community, but all the way into the world." The Buddha said: "It is not what others do or do not do that is my concern. It is what I do or what I do not do, that is my concern." Is what you're saying similar? John R. Stowe: The only place that any of us has the power to change things is within ourselves. I think almost every major spiritual teacher says the same thing. Until we do, we're just living someone else's script. Though we might know that parts of our lives aren't working so well, as long as we don't know what we really want, we can't fix them. And the only way to find out is to look inside. Society won't help much. The barrage of information, advertising, and superficiality grabbing for our attention is just too intense--and often contradictory. When we learn to turn off all the external chatter and start asking ourselves what really matters -- which isn't all that hard, once we get around to it--we tap really deep sources of wisdom and insight. From there, we approach the world from a whole different place.

Jack Nichols: It appears you've got confidence that a person doesn't need any church dogmas for a spiritual map, but is capable of creating-out of thought and experience--an effective personal map. I've often wished that some sort of process-self-creation-- could be taught in pre-school or kindergartens. Montessori schooling creates independent little tykes, I've noticed. What are some of the first steps toward spiritual self creation? John R. Stowe: The first step, I think, is deciding that you have a right to your own spiritual path. For many gay people, that's a challenge because we've been harassed and oppressed so often in the name of religion. Yet, spirituality isn't religion. Rather, it's a vital, inborn part of each of us, as natural and essential as eating, say, or exercising, or making love. It brings great satisfaction. Once we claim the right to our own spirituality, the next steps involve starting to listen to our inner wisdom. That means trusting the body and its desires. It means reclaiming the mind from old negatives. It means trusting that you have a direct and personal connection with all of being. There are many, many practices and traditions to draw on. Because each person's path is unique, the book is intended is to help each man find out what works for him personally. Jack Nichols: Our spiritual needs are seldom met by the religious traditions already serving the gay community. Would you agree? John R. Stowe: It's hard to generalize here because there are so many of us and so many different religious groups. I know that many gay people are quite happy in their religious congregations and that more and more congregations welcome and even celebrate their gay members. This is a good trend. Still, I see way too many gay people who try to change or "cure" themselves to gain approval within homophobic traditions. And that is harmful. I think the healthiest situation is when we honor ourselves enough to make our own choices. It's like coming out -- when you're trapped into a situation where you're constantly trying to repress or deny your sexuality because you've been told that God won't love you otherwise, you're stuck in a religious closet. Coming out spiritually by choosing a path that suits your own needs is a very big, empowering step. Whether you choose a traditional religious setting, something alternative, or create your own is less important than the fact of making the choice. Gay Spirit Warrior isn't about any particular religious tradition, instead it's designed to help each man make the choices that are right for him. Jack Nichols: Warrior is a word with which many conventional men readily identify inasmuch as it has long been part of traditional male role-conditioning. You mean to spiritualize the term, right? And if so, how and why? Is your book just for gay men, or is there something here for bisexual men, lesbians, and others?

Unfortunately, most of the images our own society offers as role models for warriors -- bloodthirsty, emotionless, vengeful -- I'd actually view as a gross perversion of true warriorship. And it seems that these perverted images are more and more pervasive. More people need to offer real alternatives -- and that may be us. Jack Nichols: What do you mean by "defining ourselves as gay men on our own terms?" John R. Stowe: We've spent so many years defending ourselves that a lot of our energy still goes into proving that we're not the awful things we've been accused of -- not abnormal, not sinful, not perverted, not child molesters, and so forth. As we gain more acceptance -- both inside ourselves and societally -- proving what you're not starts to fall short of what we need. It's time now to be answering a new question -- "Who are we?" Or, more personally, "Who am I? What do I love? Where is my passion? What positive qualities does loving other men give me to enjoy and share?" Once we start defining ourselves, instead of always living in reaction to our critics, we begin to creating the lives we want. Jack Nichols: Gay Spirit Warrior is experiential -- that is, designed to be hands-on and personal rather than theoretical or academic. What's your rationale for this sort of approach? Why do you focus so much on the body and what you call "instinctual knowing? John R. Stowe: I've been a bodyworker and counselor for a long time -- and I also spent a lot of years in my head, trying to understand who I was as a gay man, as a spiritual person, as a human being. What I learned is that talk is pretty easy and surface beliefs can change very quickly. The body, though, holds its own knowing, which is much less conceptual and much more primal. This is where the core beliefs live. Most of these come from very early in our lives and they tend to be where we operate from energetically, whatever we may believe with the conscious mind. Say, for example, that you learn as a boy that you're not worthy of love -- God's, your parents', your own, whatever -- because you like other boys. Even if later on you come out, find a lover, and discover that what they told you as a kid was all lies, the old beliefs can still live on -- hidden in the subconscious or carried in your cells, which is pretty much the same thing. Without ever knowing why, those hidden doubts will sabotage your efforts to find happiness and satisfaction. I've seen over and over that no matter how much we read, study, or talk about our problems, most of the time very little actual change occurs until we get down into the body and work with the core beliefs. Gay Spirit Warrior is a way for gay men to go inside and directly experience our own truth about goals, hangups, wounds, dreams, desires, and potential. The exercises are really simple, for the most part, but the experiences they offer hold a lot of power. Jack Nichols: Is this a strict methodology? How can the same process apply to, say, someone just coming out and someone who's been out for a long time? John R. Stowe: The exercises are designed to help us reach the level of our core beliefs -- and at that level, many of our issues are pretty similar -- self-acceptance, trust, choosing goals, taking action. The process provides the stucture for going inside. What each man finds there will be very personal, but the way to arrive there is similar. In practice, spiritual growth isn't really linear. Through the course of our lives, the same issues often reappear over and over. Each time they do, we have the opportunity to gain deeper insight and healing. The exercises work the same way. Of course, different parts will resonate more strongly for different people, depending on where they are in their lives. The exercises are open enough that each person can get something out of them. I'm continually surprised at how they work at different levels and even men who have been out for a long time find pieces of hidden negativity or doubt to move. Really, most of the exercises are tools that you can come back to time and again, applying them to new and different situations. Jack Nichols: How does your approach in Gay Spirit Warrior apply to the vast diversity of gay men in the community? John R. Stowe: Many of the issues we face as gay men are pretty universal. No matter what our circumstances or background, we all deal with things like learning to accept ourselves in the face of societal or familial disapproval, trusting our desires, honoring our bodies, finding satisfying relationships, and living openly in the world. Gay Spirit Warrior outlines a process that helps us access inner reality by calling on universal archetypes. Each one of us has his own manifestation of these archetypes inner personalities like the Warrior, the Lover, or the Magic Boy. The exercises on the journey help each man find out how those personalities work for him and where he can bring them into his life more positively. So whatever the specific details that come up, the process is adaptable to many different circumstances. Actually, I've had a surprising number of people other than gay men tell me that they found the exercises extremely helpful for them, too. Jack Nichols: You say that gay people tend to have special talents and sensibilities that society as a whole needs desperately. What, in fact, are these? John R. Stowe: Of course, there's a lot of individual variation, yet as a group we tend to come from a place that is quite different from the heterosexual mainstream. In many societies, the Navajo for example, and the traditional Lakotah, we were honored for our ability to act as intermediaries -- between men and women, humanity and nature, people and Spirit. In fact, we still share these qualities, though they tend to get a bit hidden under all the cultural baggage. Look at how many of us are artists and visionaries, healers, caregivers, teachers, spiritual leaders -- despite church denials, look at how many gay priests and choir directors there are. We tend to be cultural innovators who find new ways to do things -- you can think of areas like fashion and design, most obviously, though there are many others. Part of our ability comes from being "outsiders" -- viewing the mainstream from a different perspective -- yet there's more. In fact, among traditional peoples, there are many who believe that we are the ones responsible for keeping the world in balance -- and that part of the crisis facing the world right now comes from the fact that we haven't been doing our job. Not to blame us, but I tend to agree. We need to wake up and claim who we are! Jack Nichols: When you talk about individuals getting past "wounding", what do you mean by that? John R. Stowe: I mean that we have to acknowledge and heal all the negative baggage from our past -- the doubts, fears, hurts, and so forth -- that keeps us from sharing ourselves fully in the world. The specifics vary from man to man and the healing can sometimes take a long time -- especially if there was severe trauma or abuse. In those cases, I recommend getting professional help. Yet, most of us can do a great deal to uncover and revise all those hidden negatives on our own. When we do, it's as if a cloud has been lifted because we start to get out of our own way. We're better at going for what really makes us happy. Relationships get lighter. Of course, challenges still come up -- that's part of life. But when we can let go of the wounding, we have a lot more strength to deal with them. Jack Nichols: Whose work influenced you most? How did you work out this method? John R. Stowe: Most of the material comes from my own search. I came out at 23 and spent a lot of years struggling to find out what it meant to live as openly gay, self-aware, and "spiritually engaged".

During that time, I've been blessed with many powerful teachers. Andrew Ramer, author of Two Flutes Playing, and Mark Thompson, (Gay Spirit, Gay Soul) were particularly important, as well as many others, including Harry Hay, Malcolm Boyd, and Franklin Abbott. Lots of pieces came from other people who aren't necessarily gay. In addition, my personal spiritual search led me through a number of different traditions. Over the years, I put together the pieces that had given me the strongest practical results. Then, when I got it all together, I tried it out with a series of workshops for gay and Bi men.. It's still evolving, really, as each man tries it for himself. Jack Nichols: You talk a lot about archetypes. What are archetypes? Why are they relevant to gay men? What led you to choose the particular archetypes you use? John R. Stowe: For a short, working definition, I'd say that archetypes are universal characters that live within human consciousness. Each one carries the traits associated with a specific aspect of human experience -- like Mother, Lover, Warrior, and so forth. Archetypes are part of every one of us, though we all bring them forth in our own unique ways. Really, they influence us all the time -- sometimes positively, sometimes not. The goal of working with archetypes is self-understanding and empowerment --thus we can look at how each archetype manifests in our own lives and then discover ways to call on it more powerfully. Take the archetype of Warrior for an example. He's involved whenever we take action in the world. If we've learned to act directly and effectively, then that's a positive incarnation of the Warrior. If we get blocked, though, by doubts or fears or self-criticism, then the Warrior doesn't come through so positively. He still comes through, but in ways that are less effective -- as victim consciousness, for example, or self-sabotage, or overcompensatory bullying. The goal of Gay Spirit Warrior is to help us bring through the various archetypes in ways that are clear and strong and positive. For Gay Spirit Warrior , I picked seven specific archetypes that seemed to me to relate most closely to the concerns I saw in my own life and in the men around me. There's Magic Boy, the Lover, the Divine Androgyne, the Elder, the Healer/Shaman, the Warrior, and the Explorer. All of these represent major parts of our energies -- and give us a good firm foundation in the area of self empowerment. Of course there are many more archetypes. These, though, are a good beginning. Jack Nichols: How does your process help us respond to critics and the homophobia in society that would keep us oppressed? John R. Stowe: First, it helps us to find the inner strength to tackle our own doubts -- because as long as we carry internalized homophobia, we tend to support the critics. Even when we tell them "No," something in ourselves betrays us. It's an energetic thing. So our first step is to empower ourselves -- then what the critics say doesn't have anywhere to resonate. Second, it helps us gain the personal power to act appropriately and with conviction. Yes, we still need to respond to critics. By learning to empower ourselves, we can learn where to put our energy most effectively. And third, we give ourselves permission to have good lives even if some people don't like us. There will always be critics, like it or not -- and too often we can tend to say, "I can't get ahead in life until there are anti-discrimination laws," or "I can't have a good relationship until gay marriages are approved." Of course it's good to work toward reaching those goals -- but in the meantime, get the best job you can, have good relationships, do the very best you can right now. Eventually, the critics will look as ridiculous as they are. Jack Nichols: In Gay Spirit Warrior , you say that "being gay is much more than just physical attraction and sex," yet isn't this the essential commonality among gay men? What do you see as the broader experience of being gay? John R. Stowe: Of course, the sexual part is essential, yet there's a lot more going on inside us. There's an inherent energetic quality to men-loving love men that opens us to a different sort of creativity. I think this is what we sense when we talk about "GAYDAR" -- we recognize the energy. "We could characterize it as the "bridging energy" I mentioned before -- our capacity to join qualities usually seen as polar opposites, like masculine/feminine, spiritual/material, or vision/manifestation. It's one reason so many of us are teachers, healers, artists, and priests. The bridging aspect is one of the jobs I think that society most needs us to fulfill right now -- because we're facing very strong forces of alienation and fragmentation. We're are part of every ethnic, religious, economic, or national group you can think of. And as we make connections with others of our own "tribe", those bonds can help offset the isolation and misunderstanding between groups. Of course, that'll take work on our part, because we seem to be fragmenting as much as anyone else. What an important place, though, to put our energy! At another level, when we take our ability to love other men to it's fullest manifestation, we're pretty revolutionary. We show the world an alternative to the competitive domination that's gotten us into so much trouble socially and ecologically. I think it's part of the reason we're perceived as such a threat to the most conservative elements -- because we undermine the very basis for their power. Jack Nichols: You sometimes seem to use the word "gay" implying there's an essential gay spirit culture/community. Or are we bonded by our shared experience of oppression based on our sexual lives? As we become more accepted by society, do you think our sense of community will tend to lessen?

At the same time, when our only sense of community is based on resisting something else, it is naturally going to change as we achieve a measure of success. So now we see all the diversity that we'd tended to gloss over starting to be more evident, and what used to be a united front is starting to fragment. I see this as positive and inevitable, a shift to a more powerful definition of "community.". It's a sort of paradigm shift. As each of us explores and deepens his own sense of self, we have an opportunity to bond much more profoundly. When we honor our true natures, instead of trying to fit the identities given us by others, we start to discover that we're connected to other people -- gay people, yes, and also to the rest of society, and ulimately to the rest of life. This is where a truer community can be born. It's idealistic, I know, yet I believe that this is where we're headed. In fact, we have to be headed there, along with the rest of society, if we're even to survive the next couple of decades. Gay people can really help lead the way, provided we're willing to honor ourselves in all our diversity. Of course, we're human, so we'll have to see if we can rise to the challenges. Jack Nichols: You speak about personal empowerment. Conservatives often label the 70s "The Me Generation". Do they mean each of us then— who put focus on personal politics—has been just out for himself, instead of working together to improve the whole community? If not, wouldn't this imply a kind of communal or socialist spirit--as opposed to Ayn Rand-style individualism? John R. Stowe: Bottom line, we have to recognize that nobody lives in a vacuum. We're all connected. So, the first step in personal empowerment is to take care of your own health at every level -- mental, physical, emotional, and spiritual. Because what you contribute to the community is just a reflection of who you are. So if you're afraid, judgmental, doubtful -- that's what you add to the community. Your being healthy and empowered doesn't mean at anyone else's expense. Personal power just means to be all you can be. Then you can work more effectively to meet whatever goals you choose. Let's use a metaphor. If you see yourself as a cell in the greater organism we might call community -- then the healthier you can make yourself, the more you contribute to the health of the whole. In the same way, no individual cell can be healthier than the organism in which it lives. Once you start to take care of yourself, there comes a point when you realize your personal good depends on the good of the whole. And so you start doing everything you can to help the rest. Of course, it takes some of us a long time to get there, but I still think it's inevitable. And as more of us recognize it, then it gets easier for the rest. Jack Nichols: How do you see the journey you describe applying to and contributing to the most pressing goals of the gay community today? Do you think the gay movement does enough to address the personal needs and goals of individuals? John R. Stowe: Gay Spirit Warrior helps each man claim his ability to be creative and take effective action in his own life. When someone is more effective personally, he's also a lot more effective at achieving the goals he sets outside himself. The whole community is stronger because each individual within it is stronger. The later stages of the journey are about finding where each of us is called to contribute to the world as a whole. There are so many issues facing us these days -- not just as gay people, but as human beings, that each of us has to choose where to apply our efforts. Otherwise, we just get overwhelmed and burnt out. By focusing on where our skills and talents can make a difference, we not only become more empowered to make that difference, but also find great personal fulfillment in doing so. Some of us will be called to work directly within the gay community, others will be called to other areas. Every one of us who steps out into the world as an openly contributing gay person makes a difference. The gay movement, by its nature, tends to focus on big, high profile issues. There's a lot of energy around things like gay marriage and gays in the military -- worthy issues, of course. Yet, I think a whole lot of the real work is happening more quietly at a grassroots level -- things like helping gay kids come to terms with their sexuality in a homophobic environment, or dealing with issues like substance abuse, domestic violence, and so forth -- stuff that needs ongoing, one-on-one attention and that also might seem sort of like dirty laundry if it were brought up in the national forum on gay rights. Gay Spirit Warrior helps individuals more at this grass roots level by empowering them to create networks of real, day to day support. Jack Nichols: John, its been a while since I've seen you, though I've always enjoyed your company when we've connected. There's a reason for this, and it resides in you. How about describing your own spiritual path. You've been in a relationship for over 15 years. What have you learned as a result? John R. Stowe: It has been a while! My path has been all over the place. I've spent a lot of time searching, and only in retrospect does the search seem to have any sort of direction. Coming out was a major step, which I did around 1975. Having thought until then that being gay was the worst thing I could ever be, I was pretty astounded to find that accepting it was the best thing I'd ever done. For a few years, I started to look at every single thing "they" had told me about the world, figuring most of the time that just the opposite was true. Not always, but I did a lot of soul-searching! At the time I was teaching biology in a college here, which I left to study massage and healing. In the early 80's, I travelled a good deal in Central America and in Europe, trying to find a place that I could be happy. I discovered that the geographical cure didn't work. I realized that to find any kind of happiness I'd have to work on the parts of me that got in its way. So I began to explore every teaching I could get my hands on -- Buddhism, Native American teachings, psychotherapy, and all sorts of New Agey stuff. Each of these taught me pieces that were helpful, a lot of which I mention in the book. In 1984, I had a major change. I met my life partner that year, which has made life brighter ever since. We've been blessed -- not without a bit of hard work -- with a relationship based on trust, mutual-support, and a lot of humor! At the same time, I discovered flower essences. These are vibrational remedies, made in water or oil, that catalyze emotional centering and spiritual insight. I felt strongly called to make my own -- which involves energetically tuning in to guidance available from the nature realm. (I still make them -- and have them available through my website). At the time, I was totally blown away. I found myself making a major shift away from looking outside for guidance toward looking inside. I learned to trust the wisdom of the body -- both for myself and my clients and found it a great antidote to all the mental gynmastics. Working with natural healing has been a way to join my interest in ecology with my spiritual quest. Since that time, I've balanced the inner explorations with classes taught by some wonderful teachers -- body awareness and inner myths with Dominque Sire, gay spirit consciousness with Andrew Ramer and Gay Spirit Visions, vision questing, exploring creativity through writing and photography, and a lot more. In 1997, I visited the Findhorn Community in Scotland, where I was inspired to begin sharing the work on a wider scale. The journey's ongoing. Really, I'm learning how to enjoy it a lot more than I used to. Gay Spirit Warrior is available from Findhorn Press: www.findhornpress.com Toll free telephone number: 877 390 4425 or from the author at earthfriends.home.mindspring.com/exploringgayspirit.html John R. Stowe can be reached by email at earthfriends@mindspring.com The Gay Spirit Visions website is gayspirit.home.mindspring.com |

© 1997-99 BEI

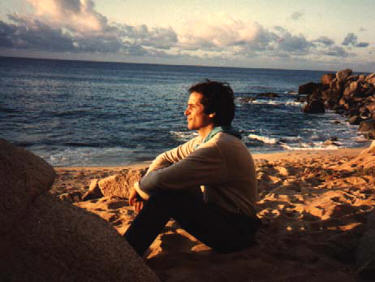

John R. Stowe

reflecting in Baja, California

John R. Stowe

reflecting in Baja, California

Members of Gay Spirit Visions at the Fire Circle

Members of Gay Spirit Visions at the Fire Circle

John R. Stowe

John R. Stowe  John R. Stowe in 1979

John R. Stowe in 1979  John R. Stowe with partner, Monty, at their home

John R. Stowe with partner, Monty, at their home