|

|

|

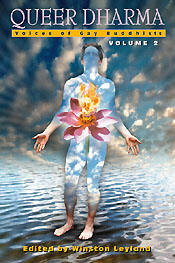

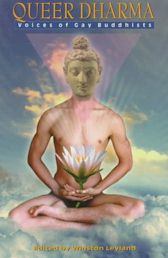

Voices of Gay Buddhists, Volume 2 Queer Dharma: Voices of Gay Buddhists, Volume 2, edited by Winston Leyland, Gay Sunshine Press, 2000, 222 pages, paperback, $16.95

Its jubilant report quoted my offhand reflections about the probable contents of any future magazine I might be tempted to edit. The Advocate zeroed in on my mention of Zen Buddhist thought as it might relate to same-sex affection, a snide attempt, as I read it, to paint my thinking as culturally askew. Having been The Advocate's first New York correspondent, however, and, in its founder's competitive mind, a renegade East Coast journalist, I gave little thought to what I considered a mere expression of mainstreamist myopia. In that colorful era, after all, GAY had represented counter-cultural gaiety. Zen, I knew from personal experience, had provided an uncanny awareness that had increasingly helped me to improve—starting when I was 30—my erotic sensibilities, thereby achieving a mind-state free from conventional blocks and worries.

Its practice had allowed me—otherwise an intense intellectual—to banish the complexities of thought so that I could better revel in the midst of physically-based pleasures. Thanks to Zen studies, I'd been enabled to experience my body's offerings with full gusto, freed from distracting conceptualizations. In fact, though I've never self-identified as a Buddhist, I have many times—in print and in conversations—used Buddhist canon to illustrate those central realizations that have infused my life with outright expressions of dauntless zest. Helping to rid myself and my friends of useless worries and speculations, for example, I've often repeated the story of two Zen Buddhist monks who, walking through a forest, encountered a naked woman standing by a stream. "Please carry me across this stream," she begged the monks, "I'm naked, and I can't go by myself." One of the monks picked her up, waded with her in his arms across the stream and then set her down. Without a speaking a word, the two monks continued their journey into the woods, leaving the woman behind.

It is not what others do or do not do that is my concern; It is what I do or what I do not do, that is my concern. Contrasting St. Paul's "Christian" theorizing with the Buddha's approach to personal salvation, the Buddha remains, in my book, by far the more helpful source. His last recorded words put such salvation into the dimension where it belongs. While St. Paul encourages believers to seek salvation through faith in an outside source, the dying Buddha advised his followers to focus inward and to find themselves through themselves: Work out your own salvation with diligence. My acceptance of this focus became particularly clear to me after I survived a major operation nearly a decade ago. In a medical specialist's office the nurse said: "You must have somebody up there looking out for you." In fact, not only had I been exercising daily, but I'd been carefully watching my diet and my sleeping routines. I'd been watching out for myself. I simply replied to the nurse: "Wrong direction." The difference between the nurse's outward-directed and the Buddhist's inward-directed approaches seemed clear to me. Life helps those who help themselves. Relying on the supernatural without relying on oneself can all too often be a sure-fire strategy for losers.

Today, snide references to my Zenist leanings would be less likely to fly. Since mid-1973, the reputation of the saintly Dalai Lama, the conversions to Buddhism of Hollywood stars and the growth of gay Buddhist groups nationwide are indicative of how 2,500 year-old perspectives have adapted themselves to new world patterns. Winston Leyland, a prominent gay press pioneer from the early 1970s, has now edited and published volume two of Queer Dharma: Voices of Gay Buddhists. The essays in this fascinating book—chapter by chapter—reveal how a variety of American gay Buddhists have imbibed ancient wisdom so as to see old Buddhist values reincarnated again today, as effectively as possible, in that satisfying realm of consciousness that can—with care-- bring about Nirvana. Among the most appealing essays is one that tells of two long-time lovers, Michael J. Sweet and Leonard Zwilling. They lived, as Lige Clarke and I once did, in New York's East Village. This was where the great poet, Allen Ginsberg, our neighbor, and his literary friends, engaged in the non-stop promotion of Buddhist philosophy. LSD consumption—with its visionary breakthroughs—had helped enamour 60s counter-culturists in this region with the Buddhist concept of Enlightenment. Especially do I now relate to this essay because it explains, as Lige and I had often done, how to apply Buddhist wisdom to same-sex relationships. The essay's title, We Two Boys Forever Non-Clinging is a word-play on the title of Walt Whitman's famed Calamus poem. Sweet writes: "Starting with generating proper concern for one's own happiness and freedom from pain, one extends this feeling to one's parents, friends and other benefactors, and eventually even to neutral or hostile people, cultivating joy in others' happiness and an impartial attitude. This can help transform the initially selfish infatuation that we feel for people, wanting them all to ourselves, wanting to control them, into a true caring for and knowing the person as s/he is." Another essay, clear and powerful, is James Thornton's Presence Makes the Heart Grow Fonder: Gay Relationship as Spiritual Practice. Thornton tells how he had once programmed himself with thoughts about his ineffectiveness in relationships. "Ultimately, though," he writes: "I saw that as long as I blamed anyone else, nothing in my experience could change. Only when I took full responsibility for my feelings, thoughts, and actions could I begin to live the kind of life I wanted, in which love and creativity could flow." Thornton provides the mantras (repetitions of valuable thoughts) he uses to overcome irritability, moodiness, and negative flows of emotion. He says: "I've been concentrating on letting the emotions, when they are strong and negative, pass through me like a thunderstorm. To do this I remember that I am the landscape not the storm. This helps me to let the storms pass through. You might try remembering this when a strong negative emotion arises: "I am the landscape, not the storm. My awareness is the landscape, and it endures, the storms of emotion blow through it and go. I am the landscape, not the storm."

Queer Dharma is a valuable addition to the literature of gay spirituality, showing how to apply extraordinary insights to our daily lives. More, it is a testament to the inventiveness and creativity that gay males have utilized in their search for the good, the true and the beautiful. Buddhism confronts not only what we think, says essayist Anthony E. Richardson, but also "how we think it." The Buddha made a point of saying: "We are what we think, having become what we thought." Just as we feed information into our computers, we must self-program our minds. There is nothing in Buddhism that requires our giving up our independent thought processes, or which insists we accept supernaturalist myths. Nirvana lies curled, a promised land, within human consciousness itself. Queer Dharma's essayists provide useful personal accounts of their journeys to that extraordinary interior we call our minds. |

© 1997-2000 BEI

© 1997-2000 BEI

In mid-1973 when my co-editor and I resigned after four years at GAY, America's first gay weekly,

The Advocate giddily celebrated our resignations as its lead story on page one.

In mid-1973 when my co-editor and I resigned after four years at GAY, America's first gay weekly,

The Advocate giddily celebrated our resignations as its lead story on page one.

Queer Dharma: Volume 1

Queer Dharma: Volume 1