|

|

|

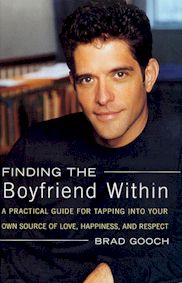

Finding the Boyfriend Within: A Practical Guide for Tapping Into Your Own Resource of Love, Happiness, and Respect , by Brad Gooch. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-684-85040-0, Hard Cover, $21.00, 171 pages. When It's Time to Leave Your Lover, A Guide for Gay Men , by Neil Kaminsky, LCSW. Harrington Park Press, an imprint of Haworth Press, Inc. ISBN 0-7890-0497-6, 274 pages, with Resource Guide and Bibliography. Hard Cover 24.95. 274 pages  I learned several things reading Brad Gooch's very quick read, Finding

the Boyfriend Within: Gymbos are the new gay take on "bimbos,"—

muscle-bound gymtroids that you tire of fast.

I learned several things reading Brad Gooch's very quick read, Finding

the Boyfriend Within: Gymbos are the new gay take on "bimbos,"—

muscle-bound gymtroids that you tire of fast.

Also, it is possible, like Brad Gooch, to spend 20 years in therapy and still not be able to accept someone else on the same terms that you'd like to be accepted yourself. And, also, that Brad leads a very with-it life. Although at 51, with moments of almost ridiculous happiness, having been involved with a lover for 19 years, I still know very little about the world that Brad Gooch inhabits. In fact, aside from its basic premise, Finding the Boyfriend Within is really a document about gay urban life of a certain type in New York and other cloned cities through the U.S. Gooch drops names of trendy restaurants, dishes, movies, movie stars, boutiques, designers—the whole "beau monde"—constantly. It seems that this is what the book is really about, although its main premise, that despite (or in place of) the vicissitudes of love, developing a real, intimate, working relationship with ones deeper, inner self—the "Boyfriend Within"—is a very good idea. Gooch personifies this personality, but as an imaginative concept the "Boyfriend" is simply a slice of what we might call the Soul and what I refer to as the Male Companion; that is, that incarnation of the place where one's deeper personality, sexuality, and spirituality meet.

This section I wish had been a bit ballsier. Gooch (and his publisher, probably) had a fear that the book would be taken to be solely a "one-handed" guide. So the author demurely skims over masturbation as a meditative technique. This it is, in Taoist practices. It is certainly a gateway from some loneliness, as well as a possible connection with others. (In other words, if you have masturbatory images about men and don't censor whom you masturbate about, it's amazing how large your erotic world can become . . . leading to some very interesting connections. Personally, I've masturbated about riding naked on a zebra with Tarzan; sucking off big old centaurs; WWF wrestlers; Van Gogh—red hair, one of my weaknesses; fat men swimming in chocolate syrup; skinny men pissing Koolaid; Jesus kissing John; John with and without Bo Derek; Aztecs tongue-kissing, and God knows how many Boyfriends Within that I've had to do without. ) Gooch's general tone is fairly genial, puppydoggish, and easy to take. He lets you in to what seems like a glossy life—his stylish Soho apartment, his personal trainer, his attractive past Boyfriends Without (who never quite seem to get off themselves and onto Brad) and you hang on like a window shopper, or one of those people who never get past the velvet ropes. He gives us exercises to do, such as list our most exterior qualities (apartments, bods, bank accounts) and inner ones (being nice, sensitive, honest), our reasons for being alone (personal ones and environmental ones, such as AIDS, careers), and gives us sample dates we can have with the resultant Boyfriend Within: making dinner with him, going out for walks, going to movies. And also what to do when you and your BFW have problems. In other words, issues. What this basically amounts to is not being alone with yourself, not feeling so isolated in our isolating world, being your own Best Friend. Then taking him out for dinner. In the long run, this is cheaper and easier than dealing with most other people and I certainly wouldn't kick my own BFW out of bed, especially if I have a real BF in there with me. Now, if I can just get that lazy Boyfriend Within of mine to go out and get me a discount at Armani's, maybe we can actually get something permanent going. If Brad Gooch's Finding the Boyfriend Within is genial, Neil Kaminsky's When It's Time to Leave Your Lover is clunky, poorly written, and "authoritative." Kaminsky, a licensed clinical social worker, has been working with a certain set of gay clients.

I found much of what he writes here to be so ridiculous it was embarrassing.

"Being with a lover," Kaminksy states, "should never be a 'settle for' experience. The

man you are with should be the man of your dreams. . . . There is much

in life we must settle for, because it is the card we are dealt. Such is

never the case with a partner. 'First class' in love is the only class

you should ever embrace."

I found much of what he writes here to be so ridiculous it was embarrassing.

"Being with a lover," Kaminksy states, "should never be a 'settle for' experience. The

man you are with should be the man of your dreams. . . . There is much

in life we must settle for, because it is the card we are dealt. Such is

never the case with a partner. 'First class' in love is the only class

you should ever embrace."

I am afraid much of the book follows in this fashion, and sounds like a 1950s Debbie Reynolds movie. Kaminksy hammers out the differences for gay men among being "married," "single," "divorced," "dating," and "tricking." He is a stickler for categories. He admits, in the last chapter, that he has had a hard time with relationships, and I can understand this. In no place does he say that the one thing that keeps gay pairs going is the desire both men have to make one another happy—and to find their lives opening up and getting larger in the process. As Gooch has a hard time with the M(asturbation) word, Kaminsky is flummoxed by the M(oney) one. He skitters nervously from it, but money, and the power behind it, is often the reason why relationships, gay and straight, fall apart. Instead, he often blames "fidelity," and holds up monogamy as the standard flag. Monogamy, to him, is "trust" physicalized. "Trust is a prerequisite for intimacy," he affirms, but, at what point are two men relieved of having to expose 100% of themselves to each other? This seems to be a gay conundrum: gay men often still don't understand that there may be of some part of themselves that they cannot—and perhaps shouldn't—share. That, as the writer Samuel Delany put so well, they may have a "secret life" they want to and need to keep secret. It may be one measure adulthood among gay men that you can allow this secret life to exist without belittling it, or trying to crash into it. But Kaminsky keeps his "No-Prisoners" attitude. "Nothing merits lying," he orders. "And no excuse for dishonesty will prevent the loss of intimacy both of you will suffer." The book, though, has its merit. Kaminsky is good on clinical ideas, such as looking rationally at damaging feeling. And his section on the importance and power of forgiveness was eye-opening. For gay men who cannot forgive their families, forgiving lovers is difficult. Neil Kaminsky has tackled the large subject of our relationships from the angle of their break-ups and the need to heal adequately afterwards. He compares a break-up to a death, which is understandable. But just as there are no "dream partners" in real life, I think you need a more embracing attitude than he shows in this book to keep from leaving the same lover, with a different face, over and over again.  Perry Brass's book How to Survive Your Own Gay Life was a finalist for

a Lambda Book Award in Spirituality and Religion—his fourth nomination.

This fall, he will publish Angel Lust, a novel about time travel. He can

be reached through his website www.perrybrass.com.

Perry Brass's book How to Survive Your Own Gay Life was a finalist for

a Lambda Book Award in Spirituality and Religion—his fourth nomination.

This fall, he will publish Angel Lust, a novel about time travel. He can

be reached through his website www.perrybrass.com.

|

© 1997-99 BEI

© 1997-99 BEI