|

|

|

|

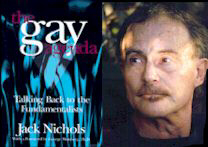

| By Jack Nichols

The Stonewall Inn, between 1967-1969, was often a fun place.

Only a few years before, I'd frequented the Ce Soir, one of Gotham's two gay "dance" bars where, in a back room, a light bulb hung ominously from a single cord, ignited whenever an unknown customer entered the front door. The lighting of the bulb signaled that dancing couples must separate. In June, 1969 The Stonewall Inn was light years away from this furtive past, attracting the arrival of what media soon began calling "the new homosexual," emboldened by the 60's counterculture, by new standards challenging gender roles. Pot --the good weed-- was, in those days, the drug of choice.

When straight hippie males made love to women in each other's company, touching other males became less fearsome, producing, for an extended time, a phenomenon the media called bi-sexual chic. Gay-baiter Joseph Epstein, writing in Harper's (1970) told of his shock after he'd asked his long-haired seventeen year old straight hippie stepson what he knew of "the new homosexuals." "If you mean guys buggering each other," replied the boy, "it goes on all the time, and drugs don't necessarily have to be involved. 'You scratch my back and I'll scratch yours,' is kinda how guys see it." My own late-Sixties early-Seventies experience confirmed this boy's perspective. I began hoping--in contrast to ghetto separatists-- for a final melting of gay/straight divisions and the creation of a sexually integrated society in which everybody would free to love and make love without self-identifying through specialized sexual labels. I hoped that the developing demand for the equalization of the sexes would help bring such a world into being. The counterculture revolution was seen by gay conservatives and by right wing politicos as a threat to the social order. The gay conservatives sought a world in which previously acceptable heterosexual standards were to be implemented in gay circles. They established gay Christian churches, sought to have their own children not through adoptions but through artificial inseminations, suggested imitation establishment marriages, and asked, along with heterosexual males, the right to fight and kill for a belligerent Vietnam-punishing Uncle Sam. The conservatives we have with us always. But the straight counterculture, and "the new homosexuals" were going, during the Vietnam war, in another direction, declaring themselves "gay" at the draft boards to muddle conscriptions and to denounce the war. In our columns Lige and I called for "buggering up the barracks" and "clusterfucking for peace."

Our militant gay activism had preceded the Stonewall uprising by nearly a decade. In 1965 we'd launched picketing in Washington's direct action group, the Mattachine Society. But it was a foiled police raid on the Stonewall Inn in late June, 1969, that first caught the media's attention. The Stonewall uprising offered just the right mix of dramatics: youths fighting back for the first time against police corruption, the stuff of a legend. Almost immediately, it became clear there were those who would integrate gays into the mainstream culture and those who believed that culture to be unredeemable. As gay columnists writing for the then-zany SCREW, an otherwise straight tabloid, and for the gay newspaper, The Advocate, Lige Clarke and I wrote the first journalist's published accounts of the Stonewall rebellion and, because of our counterculture underpinnings, we not only celebrated it, but called on the youths of our time to press the Stonewall uprising beyond its narrow boundaries. On July 8, 1969, sounding the counterculture's view, we issued this "call to arms": The homosexual revolution is only part of a larger revolution sweeping through all segments of society. We hope that "Gay Power" will not become a call for separation, but for sexual integration, and that the young activists will read, study, and make themselves acquainted with all of the facts which will help them to carry the sexual revolt triumphantly into the councils of the U.S. government, into the anti-homosexual churches, into the offices of anti-homosexual psychiatrists, into the city government, and into the state legislatures which make our manner of lovemaking a crime. It is time to push the homosexual revolution to its logical conclusion. We must crush tyranny wherever it exists and join forces with those who would assist in the utter destruction of the puritanical, repressive, anti-sexual Establishment.

"This was part of a 'vision of liberation,' as novelist Michael Rumaker wrote, encompassing more than gay rights: 'The larger vision was the death of flesh hatred and shame.' " We hoped to see (fulfilled non-coercively) every person's natural sexual curiosity instead of its being a source of embarrassment and titillation. Pornography and possibly rape, we thought, could only thrive where sexual repression remained rampant. "Make Love Not War," was much more than just a slogan of the times. As a counterculture theme it said that sexual repression and moronic macho posing must be dismissed because the frustrations resulting from these were root causes of a widespread militaristic mania. Violence, in other words, was defined as the great obscenity. Former Secretary of Defense McNamara's belated confession—that he'd always known that the war he'd championed was unwinnable-- seems now to have justified this definition of violence. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.—in the midst of the government's military madness-- had insisted that unconditional love would "have the final word in reality." But America's conservative establishment would not be easily swayed, in spite of the many signs that pointed to needed change. Traditional institutions armed with vast financial resources, went on the offense, re-grouping against this splendid challenge to their oppressive programs. They would later work to discredit and muddle the counterculture's saving visions expressed through its gurus such as Theodore Rozak, Paul Goodman and Alan Watts. Watts was wonderful. The fun-loving Zen scholar, far ahead of his time, wrote: "If they (young and unrealized homosexuals who affect machismo, ultramasculinity, and who constitute the hard core of our military-industrial-police-mafia-combine) would go and fuck each other (and I use that word in its most positive and appreciative sense) the world would be vastly improved. They make it with women only to brag about it, but are actually far happier in the barracks than in boudoirs. This is, perhaps, the real meaning of 'Make Love, Not War.' We may be destroying ourselves through the repression of homosexuality."

Following on the heels of avant garde feminism and the successes of the black civil rights movement, gay liberation began, after Stonewall, to gain some measure of wary recognition from a media that had deliberately ignored the earlier more peaceful picketing demonstrations at the White House, Independence Hall, the Pentagon, the Civil Service Commission and the State Department.

Following on the heels of avant garde feminism and the successes of the black civil rights movement, gay liberation began, after Stonewall, to gain some measure of wary recognition from a media that had deliberately ignored the earlier more peaceful picketing demonstrations at the White House, Independence Hall, the Pentagon, the Civil Service Commission and the State Department. Michael Bakunin's anarchist slogan, "None of us are free till all of us are free," reverberated in the meetings of New York's Gay Liberation Front, established on the heels of the Stonewall rebellion. I was heartened by this, but soon became disheartened when I saw GLF fall prey to dogmatists who effectively split the energies of its idealistic membership. The Gay Activist Alliance, (contrary to impressions given in revisionist, error-riddled histories like Martin Duberman's Stonewall) inherited those Stonewall energies, and GLF largely disappeared from the New York scene. GAA, on the other hand, focused on the gay issue alone, and in a series of daring "zaps" served notice through direct action that a new era was at hand. There were those of us interested in other causes and who saw how gay issues connected with them but to the Stonewall era's generation of activists, focus on gay issues, needed after long and impossible silences, seemed essential. I made my peace with my more conservative friends by saying that the gay counterculture, on the one hand, and gay assimilationists on the other made, perhaps, two sides of a coin that, once spent, would pave the way for all same-sex lovers toward greener pastures. But I've remained, through the years and even in the face of the gay and lesbian movement's major successes, sorry that the clear voice of the counterculture--questioning established institutions--has been mostly drowned out by a more vocal gay establishment seeking acceptance among the power players in the status quo. One of the singular values of gay liberation, therefore, gets lost, specifically its being a catalyst and encouraging, as it should for anybody who thinks about what the gay struggle reveals, skepticism about the shaky-idea foundation stones supporting the status quo. On the fringes of the gay and lesbian movements we do see small counterculture groups and publications today—like the Radical Fairies (founded by gay liberation pioneer Harry Hay), RFD magazine and Gay Spirit Visions. Such groups carry on some of the traditions of the Sixties counterculture, though not by using strategies I myself might choose. Their voices are, as is the case of mainstream heterosexual radicals, kept to a low volume by the establishment's powers. Left on the playing field of the present—as we sit on the doorstep of the millennium—are the huggers of customs and rituals. Instead of questioning the failing institution of marraige, some gay men and lesbians are flocking to it. Instead of showing concern about the overpopulation crisis, some gay men and women are flirting with artificial insemination, producing more children. The current issue of The Advocate features on its cover— and in its "biggest issue ever"—gay parenting. The coverwoman, Melissa Etheridge, is shown sitting on her instrument case. She holds—casually-- a baby carriage and the bumper-type stickers on her case read: "Baby on Board" and "Proud PTA Mom". Is this going to be the way gay and straight integration takes place? Perhaps, to a degree. Don't Ask, Who Cares? Instead of denouncing the excesses of institutions like the Pentagon and an economy based on what Eisenhower called "the military industrial complex," many gay men and women seek to be a part of that insidious complex. Instead of denouncing St. Paul, gay churches have sprung up in support of his twisted theories, subverting morality as they do with self-hate doctrines like the atonement. A negative view of sex and sensuality has returned forcefully in many locales as a result of the AIDS crisis. An entire generation's brightest and kindest have been cut down as a result of this plague. Sensuality--having become unnecessarily frozen in the midst of plague fears—has morphed into a clumsy but sentient baby which lives in our aspiring passions but that too often gets thrown out with the very bath water that generally causes our social rigidities. The counterculture had heralded a sexuality that re-invented traditional American values. It had little of the old American culture's goal-orientedness which leads to anatomical or genital-overfocus and which too often downplays affection, failing to encompass, as the new culture had demanded, the whole person/body. Rolling, licking, kissing, stroking, and touching, were all acts that got included in the counterculture's non-penetrative word for sex: balling. Today I marvel when I see what's been accomplished in a mere 30 years since the Stonewall uprising. Since that first gay march at The White House in 1965, when only ten people --three women and seven men (including myself)--took part, I've watched our capital city's gay and lesbian demonstrations grow size-wise over the decades--expanding into what we only dreamed about early on. I've seen a U.S. President speak out repeatedly on behalf of same-sex love and affection, and I've seen a giant community of gay men and lesbians rally to care for the sick and the wounded in this World War Three against AIDS. Even if it is, in certain ways, a sexually-segregated community still, I continue to hope for a much-integrated future where, as prophesied by Walt Whitman, men will blur distinctions by walking hand in hand in America's streets because, as he well knew, same-sex love is not a gay matter alone, no, "the germ is in everybody."

Jack Nichols is Senior Editor at GayToday www.gaytoday.badpuppy.com and

author of The Gay Agenda: Talking Back to the Fundamentalists (Prometheus Books).

John Loughery, art critic for the Hudson Review and author of the award-winning The Other Side of Silence: Men's Lives and Gay Identities: A Twentieth Century History (Henry Holt, newly out in paperback) says of The Gay Agenda: "With all the passion of his heroes, Walt Whitman and Thomas Paine, Nichols is the individual with a wide view, grounded in both literature and activism. He not only talks back to the fundamentalists, he talks back to us…above all about the dignity of our struggle."

The Gay Agenda can be ordered for $18.87, a 30% discount off of the

regular hardback price of $24.95. To order from Prometheus Books,

explain you'd like a GayToday reader's discount: 1-800-421-0351

Jack Nichols is Senior Editor at GayToday www.gaytoday.badpuppy.com and

author of The Gay Agenda: Talking Back to the Fundamentalists (Prometheus Books).

John Loughery, art critic for the Hudson Review and author of the award-winning The Other Side of Silence: Men's Lives and Gay Identities: A Twentieth Century History (Henry Holt, newly out in paperback) says of The Gay Agenda: "With all the passion of his heroes, Walt Whitman and Thomas Paine, Nichols is the individual with a wide view, grounded in both literature and activism. He not only talks back to the fundamentalists, he talks back to us…above all about the dignity of our struggle."

The Gay Agenda can be ordered for $18.87, a 30% discount off of the

regular hardback price of $24.95. To order from Prometheus Books,

explain you'd like a GayToday reader's discount: 1-800-421-0351

|

© 1997-99 BEI

Marchers during the first anniversary of "Christopher Street Liberation Day"

Marchers during the first anniversary of "Christopher Street Liberation Day"

Jack Nichols

Jack Nichols