|

Self-awareness of my own character was an evolutionary process. I cannot claim that I was always happy or secure in my youth, as I was uncertain of that which I inwardly sought to become. Integrating my appreciation of art and culture with a strong moral foundation inevitably defined my adult life. One thing that I always knew was that I was to forever be on a journey of discovery. Fortune intervened, even in the darkest times of my life. As a young adult, success came easily to me in terms of my career and personal relationships, and I acknowledged this blessing. But, at a particular stage in my late twenties and early thirties, I had an overwhelming premonition that I was in the midst of the best years of my life -- and that it was only temporal. I was in a loving relationship, I owned my own home, and had a promising and fulfilling career. I knew that this period would be relatively short and was soon destined to end. In 1990, my partner was diagnosed with AIDS. He soon succumbed after a string of devastating illnesses. I helplessly witnessed the horror of a loved one, relatively young and vibrant, slip Painfully away from the world and people he so adored. Clearly, this was the omen that foretold of the sharp turn of my own fortune and comfort. Suddenly, I was plagued with health issues that ultimately led to the loss of my eyesight, my career, and emotional well-being. It was apparent that I would need to fight vigorously if I chose to survive. I was at peace with the notion of letting go. But, several factors, including a compulsive nature brought to the surface a source of mysterious strength and courage. Adaptation to this new paradigm demanded that I seek a greater purpose for my continued existence. It was never again going to be easy as it was before. When my life started to realize some of these "greater purposes", I was once again to be challenged by the most traumatic series of events I'd ever experienced. This string of calamities all occurred within the span of time during which I had found my voice as a published author.

Raj Ayyar: What is your upcoming book Songs of the Blind Snowbird all about? Can

you share some of the highlights of the book with readers of Gay Today?

Raj Ayyar: What is your upcoming book Songs of the Blind Snowbird all about? Can

you share some of the highlights of the book with readers of Gay Today?

Robert Michael Jacobs: It was difficult to concisely, yet briefly answer that question while engaged in the process of creating this volume. Eventually I composed this response: The Songs of the Blind Snowbird chronicles a real life journey through a complex and cluttered world in total darkness. This statement applies both literally and figuratively. From the perspective of a blind author, many commonplace issues get caught in the spotlight that are easily overlooked or seem invisible to the casual observer. The book employs humor and irony in short anecdotes. The entire collection of compositions combine engaging storylines with the sequential series of the popular published thematic columns. A natural relationship develops by intertwining the columns with concurrent actual stories and dramatic events. The narratives range from the absurd to the surreal, reflecting true-life experiences. The individual pieces vary in style, format and tone -- as incidents and observations are recounted through voices ranging from satire to deep anguish. The entire work covers eighteen very eventful months of the author's life. During this expanse of time, Rob traveled a twisting path of exhilarating successes and traumatic turmoil, which included ruthless police brutality, cancer, unconditional love and death. Each storyline becomes a thread woven throughout the book. Personal accounts range from amusing to bizarre. Three main themes permeate the volume. One is a personal experience of brutal assault at the hands of the Key West Police Department. The ramifications of this traumatic event constantly develop into related stories.

The columns, contained within the book, were originally designed to be able to serve as stand-alone pieces for those who could not view the entire series. Compositions contained within enlighten by providing the perspective of a blind citizen living among a sighted population. They often illustrate the challenges faced in our complex, commercial, and visual culture. A sincere effort is made in each piece to expand this angle, as it would apply to all citizens, regardless of their circumstances. Blindness nearly becomes a metaphor for the challenges and obstacles faced by all individuals seeking peace, happiness and well-being. Through candid dialogue with the reader, Rob tries to reduce people's fears of those different from themselves. If such serious topics can be approached in an entertaining manner, Rob believes that great meaningful strides can be accomplished among our societies." Raj Ayyar: In Songs you say that "Faces are only masks", and challenge the lookist assumption that beauty equals goodness. Has your blindness sensitized you to the appalling lookism and ageism in gay as well as mainstream American cultures? How do we go beyond the beauty and youth fetish? Robert Michael Jacobs: In my writings I have tackled this issue with vengeance, using wit and farce instead of cynicism. Perhaps unfairly, I frequently target gay culture in particular for such superficiality. I claim to be no wiser than anyone on this subject, but my blindness has granted me a perspective that certainly magnifies the issue. (I hope I wasn't equally as judgmental before blindness as those I encounter today.) I disdain the shallow character of those whose idealistic virtues are based primarily on youth, beauty and stylishness. In regards to your second question, I have no good answer as to how we could overcome such twisted values in a society that is built around this warped sensibility. Teaching and enlightening children at an early age may help to some degree in the formation of an individual's character, but societal pressure has the force of undoing such direction. Only when one becomes old, disabled or outcast will the lesson of such early education attain its essential value.

I broadened my exploration to find personal healing through massage therapy, eastern philosophies, western medication, sexual and erotic therapies, meditation, fatalism, mysticism and pure pragmatism. Activism and meaningful employment provided the drive to survive. Even after seven plus years, no total sense of acceptance has ever thoroughly permeated my being. As I am so often complimented on my "adaptation", I graciously accept such comments. I mask the personal pain and frustration for the benefit of others, but discreetly know the truth of the tears that fall on my pillow. I resent feeling forlorn, and make an intense effort to avoid appearing pitiful, so I project an image of strength. The most passionate creativity is frequently rooted in pain. An undeniable human need to be expressive can be directed to employ the tools of humor and irony. My goal is to articulate by engaging a reader through a creative process of entertainment. Inadvertently, a reader might start to "see" the world around them with a new sense of vision. Raj Ayyar: Has the insensitivity of the sighted opened you up to a cognitive and emotional space of empathy with anyone who's an oppressed 'Other' in our society? Gay people, the homeless, Brown people in the US post-9/11 and so on? Robert Michael Jacobs: First, I need to emphasize that for all those "insensitive sighted" people that I encounter, there are (hopefully) vast numbers of individuals who are kind, sensitive and loving. Many such people have entered my life as a direct response to my situation. Next, I would prefer to believe that I had always been aware of the disenfranchised living amongst us and on the fringes of our society. It is very likely that I have developed a greater sensitivity as a result of blindness. There is one column included in the book that specifically deals with that topic, and how, as a blind man my own inclusion in this group has added another level of minority status to my life. In turn, I experience increased encounters with such fellow citizens. I am forced to admit that few can truly understand how hard life can be for the disabled, how excluded one can feel from general society, and feelings of awkwardness or self-consciousness takes a place in daily interactions with others. I address the topic in light of a new sense of multi-cultural diversity needing to expand its definition to be more inclusive than the mere obvious. As each individual is unique and distinctive in some way, a broader mindset must apply to our rallying of mutual respect. Raj Ayyar: How has the loss of eyesight affected your life as a gay man? Has it made a significant impact on your sex life? Worsened a sense of oppression and loneliness? Have sighted partners and friends backed away from relationship, muttering embarrassed nothings?

On the other hand, if the other person is fearful or feels awkward in approaching me, we both might have missed out on something. If "cruising" has been raised to an art form by the gay male social circles, then I am definitely at a major disadvantage. Feeling isolated, even in the midst of a crowd, I must wait to be approached. I can recall several incidents of men who were unaware of my blindness, and later told me that they had assumed I had been acting aloof. In other instances, I may spend many hours speaking with another and be totally unaware of the subtleties of body language. If my interest in another person is peaked by stimulating conversation, I may have no clue regarding sexual attraction. When emboldened, I resort to physical contact just to learn what others can detect by a subtle glance. I've written accounts of my damaged Gaydar, and the inability to mingle with ease. My current single status may be a testament to the reticence of others to date one limited by my disability. Gay culture can be cruel to those who do not fit a certain model. I am also more vulnerable to less-than-scrupulous guys, and have been the easy target of theft and deception. Yet, in other instances, blindness has added a dimension to sexual encounters in very playful ways. Once made aware of my blindness, a guy may act more thoughtful or be less inhibited to act sensuous, passionate or creative. Raj Ayyar: Tell us a little about your work with animal rights and protection. Robert Michael Jacobs: I had never been allowed to have a pet dog when I was young. But, as an adult I finally had the option to expand my family to include a dog. Immediately I recognized the metaphysical wonders of this companion species. From the start, I made every effort to share (my Yorkshire Terrier) KC's instinctive ability to heal, comfort and teach. We visited hospitals and nursing homes. In short we expanded this personal endeavor to include hospices. In many of the book's segments, I recount the incredible effect KC had on people. In 1995, when I lost my eyesight, his existence in my home saved my life, I came to understand an even greater destiny. I linked up with program coordinators at the MSPCA to develop an initiative to assist people living with HIV to maintain their beloved pets. KC and I became their first clients -- developing the outline of this new program, and subsequently becoming their spokesman/dog in the Boston area communities. We toured and lectured before Veterinary schools, Nursing school classes, and perhaps most importantly, before scores of prospective volunteers. It is not an exaggeration to say that I have never ceased to be amazed at his ability to bring out the finest of human traits. I credit him with the massive success of the program to help hundreds of clients, raise tens of thousands of dollars, and recruit dozens of new volunteers. This program (Phinney's Friends) was the pinnacle of a humane society effort to help both humans and animals. By recognizing the bonds that existed, and the health benefits animals bestowed to their humans, the program's success became one of my major passions. Raj Ayyar: There's a sentence in your website www.robertmichaeljacobs.com that caught my attention. "Rob feels that by presenting his unique point-of-view he can recapture his creative ambition for a greater social purpose." What is that greater social purpose? Robert Michael Jacobs: Here's where I run into the danger of sounding arrogant, self-righteous or morally superior. I've heard my writing coming off as bitchy, condescending or pompous. I take it as the price for holding up a mirror to my fellow citizens and forcing them to see things from a new dimension. Believe me, I edit my work to death with the aim of avoiding such a negative appearance. I try to draw people in with humor, literary artistry and the intrigue of reality. I try to use the word "enlighten" instead of "educate", as nobody wants to tune in to be lectured. If people have taken offense at my bluntness, it sure hasn't stopped them from reading my work. I get far more accolades and expressions of gratitude from readers than criticism.

Raj Ayyar: Rob, you work as an ESL instructor, teaching new immigrants English. Are your students more angry, jittery or just plain scared than before with the massive reign of terror unleashed by the Bush administration, replete with false arrests, suspension of due process, new tightened INS regulations and constant surveillance all in the name of 'Homeland Security?' Robert Michael Jacobs: My initial reaction to this inquiry is that in recent times, few students have had the mastery of the American English language to vocalize their political observations. In the past, before the geo-political climate of our new century, most of my students had emigrated from the former Soviet Republics. In their eyes, and at that time, America truly did appear as the land of freedom and opportunity. I've watched as the children of my first students from one decade ago, have succeeded in attaining a great education and promising career opportunities. In contrast to the repressive lands of their origin, America did not have the overt appearance of repression, corruption or social fear. The joy of learning, seeking new ambitions and finding the potential for their offspring to freely discuss and alter political landscapes was incredible. I had begun to lose faith in the new American-born generation to achieve the ideals so strongly vocalized in the decades of my youth. The immigrant population has historically given rise to greater social change. I am inspired by the vigor and promise of new citizens to re-instate justice in a country that has lost its vision. Raj Ayyar: In Songs of the Blind Snowbird you talk about the insensitivity and ignorance of the "Sighted-Blind." How can we re-educate morally blind sighted people about the issues and concerns of the blind? Robert Michael Jacobs: I guess that I see that as one of my jobs. Understandably, some people's fear of the blind is rooted in a previous unfortunate personal experience. Upon approaching a blind person in an offer to assist, they may have been rebuffed. Many blind and disabled persons are too proud or angry to accept help graciously during a public encounter with a stranger. Thereafter, the helpful pedestrian is wary about a similar engagement. Through my writings, interactions and behavior, I hope to encourage everyone to be more supportive of each other, whatever the circumstances, and retain less fear of making a blunder. In the last sentence of my first column, I invited my fellow citizens to "allow me to help you to help me". I will teach others the correct way to assist, or politely decline an offer with a gesture of gratitude. Acquainting the general public with the issues and concerns of the blind should be only one part of educating people to be more aware of the world around them. It takes only a small application of common sense to determine what special needs any person may require in a given situation. When people are so self-absorbed that they are blind to the impact of their own behavior to others, their sense of reality is out of balance. Prevalent attitudes of ignorance, thoughtlessness and selfishness undermine any attempt at attaining a "morally concerned" sense of community. Attitudes need to change. People will then come to realize that generosity of good will returns to the giver many times over. I can enumerate many specific concerns of which the general public should be aware. But in the interest of brevity I will site just two examples that I allude to in my writing. Both concern equal and fair access issues. Whereas media outlets have matured to the effort of inclusion for deaf audiences via ASL (signing) to accompany staged productions and closed captioning for the electronic media markets, most are unaware or active in making a parallel access format available to the sight-impaired. I touch upon two examples in my writing. First there is the debate regarding whether or not the Internet is public space. If deemed so, web designers should conform to the set of standards published by the Web Access Initiative (WAI). And film and television production can be more inclusive by implementing Descriptive Video Service (DVS), which describes the action on a secondary audio channel that runs in sync with the program. As with most new initiatives, special interest consumer action groups face a formidable level of corporate and government resistance. Raj Ayyar: Do you have any projects planned after the publication of Snowbird? Robert Michael Jacobs: I will continue to try to get out my message. The publication of this book may accomplish this goal for the present. The "business angle" of promoting this publication is exhausting -- both in terms of energy and time. I long to be able to sit and compose words again for the creation of art. I have been recording pages of notes for future works. What form they will ultimately take is unclear as of yet. Raj Ayyar: Looking back on your life, both sighted and blind, is there any sense in which you have reframed your blindness as a harsh but valuable teacher? Robert Michael Jacobs: Interestingly, I think it has made me a better ESL tutor. Suddenly, with the advent of total blindness, I learned first-hand what it is like as an adult to need to start all over again in life. Both teacher and student have each brought only the core remnants of our character into a strange new world. Additionally, no pun intended, my eyes have been opened to many aspects of reality that were hidden in the bright illumination of plain sunlight. The diversity of human nature is as broad a spectrum as outward physical human characteristics. In this journey through the shadowy landscape of my current life, I have had the opportunities to encounter the brightest, most generous souls, as well as the darkest, most despicable ones. When I first lost my eyesight, I was truly blind in that I saw no reason to survive and fight. But a hard life can make a hard and solid being. I've said previously in this interview that my decision to choose survival was rooted in compulsions. Even if all the fun were drained completely out of my life, I knew that the mysterious source of strength that rallied me was a greater power than I was able to understand. Nonetheless, it virtually commanded me to move forward and do whatever was in my means to make such a cataclysmic event less painful for others who also travel along this road. Raj Ayyar: Is there anything else that you would like to share with readers of GayToday? Robert Michael Jacobs: Yes, I always have more to say. But I try to limit my verbiage before I lose the attention of my audience. So I will try to slip in two more points: If we can possibly refrain from identifying many social issues as specifically gay, racial, disabled, ethnic, economic-class, and so on, perhaps we can unite in creating a more just and rational system. I know it is hard to respect someone you hate, but direct your anger to hateful ideas, not people. Accept the fact that some people will always refuse to alter their viewpoints. Most likely it is based on their own selfishness. Most fears can be resolved, but the selfish person lives with the threat of losing title, wealth or position. One last thing: I believe that there will always be mysteries. One can go crazy trying to find rational explanations for everything. Believe me, I've been there! |

|

Author Robert Michael Jacobs and his pup

Author Robert Michael Jacobs and his pup

Robert Michael Jacobs at work

Robert Michael Jacobs at work  The author and one of his beloved canine companions

The author and one of his beloved canine companions  Robert Michael Jacobs relaxes in Key West

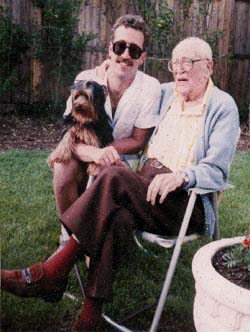

Robert Michael Jacobs relaxes in Key West  Robert Michael Jacobs, his canine companion KC and his Grampa, Dave Michaels

Robert Michael Jacobs, his canine companion KC and his Grampa, Dave Michaels