|

Oil & Cable TV (Part II) By Bill Berkowitz

"There is only one job in the United States and the world, I suppose, that would give me any more opportunity to do good for my fellow man. That would be the presidency." Six years later, in a 1985 interview with the Saturday Evening Post, Robertson commented on a possible presidential run: "Of course, you always have to consider what the Lord wants. If He were to say 'Run for president,' then obviously any man of God would have to obey. The whole thing would depend on what He wanted." Robertson, taking his cue from on high, decided that 1988 was the year to seek the Republican Party's presidential nomination. And although his bid ultimately failed to galvanize broad electoral support, he managed to raise $11 million. Along the way, he also organized a petition drive that resulted in the collection of hundreds of thousands of signatures of potential supporters. Robertson turned these names into "an enormous mailing list" for future fundraising solicitations. He took that list, developed a computerized database and used it as the basis for founding the Christian Coalition in 1990. With Robertson at the helm and the subsequent appointment of the cherubic and politically savvy Ralph Reed as executive director, the Christian Coalition took off. Donations poured in, membership soared, conservative politicians showed up in droves at the Coalition's annual "Road to Victory" conferences, and the organization perfected the art of the one-sided voter "guide." Within just a few years, the Coalition became the dominant grassroots political operation on the Religious Right - at one point claiming nearly 2 million members and an annual operating budget of almost $30 million. Since 1999, the Christian Coalition has been sliding downhill at breakneck speed. There have been a number of internal problems and organizational discord. Not long after Reed's resignation, Robertson appointed and then fired a new executive director and president; the organization was charged with discriminatory practices in a suit filed by several African-American employees; it was sued by a direct-mail marketing firm for not paying its bills on time; membership roles shrank; its flagship publication, The Christian American, was shut down; it was denied tax-exempt status after years of haggling with the Internal Revenue Service; and it downsized its staff last year when it moved its headquarters from Virginia Beach, Va. to Washington, DC. Then, in December 2001, Robertson resigned as president and longtime Coalition activist Roberta Combs was given the unenviable task of rebuilding the organization. CBN's television empire

Out front is the 240-room Founders Inn hotel, with its reproduction oil portraits of Washington and Jefferson - along with CBN founder Robertson, clutching a Bible and standing before an undulating American flag. Nearby is the National Counseling Center, CBN's 24-hour telephone center, which gets some 2.5 million calls a year from people asking for help and being asked to give. Over 200 'prayer counselors' carefully track incoming calls, allowing CBN to analyze The 700 Club in 30-second intervals to find out which pieces drive pledges and which drive them away. Some 93% of pledges come in when The 700 Club is on." Within walking distance, is the campus of Regent University "including the 130,000-square-foot Robertson Hall (which houses his ACLU-battling group, the American Center for Law and Justice); the university's airy library; and a new, $35 million College of Communications and Arts, which when completed will feature a movie back lot, $6 million of digital video equipment, and a 750-person auditorium." Despite the formidable empire and a CBN viewing audience that hovers around 200 million people in 90 countries and 71 different languages, Robertson isn't satisfied. He hopes to reach one billion people a year by 2007, writes Roth. Robertson has given the task of globalizing CBN to his youngest son Gordon. Roth writes that "in the past few years, the onetime lawyer has opened studios in India, the Philippines, and Ukraine, cloning The 700 Club and creating" new programs and a $5 million studio in Indonesia. "In less developed countries," Roth says, "CBN employs 'blitzes' - attempts to expose a population to Jesus by buying up as much airtime on as many media in a country as possible. Since the early 1990s, CBN has launched its media strikes in some 31 countries." But, these lofty plans are expensive. Roth claims that during the past three ears both CBN and Robertson's charitable organization Operation Blessing "have been running in the red, losing $37.5 million on revenues of $202 million in the fiscal year ended March 31, 2001." Donations to the "700 Club" and Operation Blessing are how Robertson makes most of his revenue - $95 million to CBN and $66 million to Operation Blessing. "Of that," Roth writes, "CBN spends $90 million staffing its National Counseling Center and producing and syndicating its shows in the U.S….International outreach costs an additional $24 million, with much of it going to offices, studios, and the blitzes." Will CBN be able to continue garnering such bountiful donations after Robertson is gone from the scene? Roth thinks the operation is in trouble. "Personality-oriented media ministries generally do not last long beyond the death of their founder-leaders," Quentin Schultze, a religious-media expert and professor of communications at Calvin College in Grand Rapids, told Roth. "Some religious-media personalities try to usher their offspring into the celebrity fold, almost as a kind of religious monarchy," Schultze notes, citing Oral Roberts, Robert Schuller, and Jimmy Swaggart. "But there is no historical evidence that this kind of monarchical passing of the ministry will be successful." That is where the hunt for gold and oil comes in. Robertson's Liberia escapades Last December, Robertson's Christian Broadcasting Network provided programming that for eighty nights in a row dominated the two television networks in Liberia, reports Daniel Roth. "There was the Prodigal Son parable told from a Nigerian point of view; animated Bible episodes; stories about people who said they'd had out-of-body experiences and come face to face with the Almighty; and the true tale of a Mexican family who stayed together thanks to God."

There a crew of 35 Liberians were digging deep holes into the red, claylike soil on a plot of land contracted out to Robertson. Their goal was to uncover the spot, beneath the gravel and laterite, that they believed held five million ounces of the stuff that the Book of Revelation says lines the streets of heaven: pure gold. Gold that if sold on the open market could reap about $1.5 billion." (For more on Robertson's Liberian ventures see columnist Colbert King's articles in the Washington Post: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A7124-2001Sep21.html.) Southern California oil venture sours In August 1998, Robertson bought the Powerine refinery, a plant once owned by Rothschild Oil, in Santa Fe Springs, California, a largely Latino community. The plant had been a target of vigorous community protests over its lousy environmental record and was shut down in 1995. But, writes Roth, Robertson was convinced by colleagues "that for a $20 million initial investment, he could restart the plant, run it right, and pump out profits of $70 million to $100 million a year." Robertson named the new operation Cenco Refining, short for Creative Energy Co. What Robertson "didn't count on was the community response" to his deal, writes Roth. "The old Powerine refinery was despised in Santa Fe Springs. While residents weren't thrilled about the eyesore of the rusting facility, they preferred it to what they used to deal with: irritated eyes, breathing issues, and strange oil patches that at times coated their cars. When Powerine was running, it earned the distinction of having the worst air-quality record and highest number of public complaints of all refineries in the Los Angeles area." Communities for a Better Environment (CBE), a politically savvy environmental health and justice organization got involved, charging Robertson's plans to reopen the 65-year-old refinery would endanger the health and lives of tens of thousands of area residents - many of them children. CBE also noted that the previous owners of the refinery had paid hundreds of thousands of dollars in fines for safety and pollution violations. CBE's organizing activities weren't the only problems CENCO had to contend with. According to Roth, the "state also sued for hazardous-waste violations, the city of Santa Fe Springs for other hazardous-waste violations, and the Environmental Protection Agency for air concerns. Soon even Robertson's lawyers were joining the act, alleging that Robertson had stopped paying their bills. (Cenco says it plans to countersue one law firm and settle with the other.)" Last year, despite a favorable ruling from the South Coast Air Quality Management District - the California government arm that regulated the region - declaring that Powerine's old permits were still valid, the CENCO investment was "was draining CBN's endowment, not enriching it." Roth: "Cenco's overhead operating costs by last fall were about $325,000 a month. Throw in the 8% interest it was paying on loans, and the carrying costs soared to $485,000 a month. Robertson had had enough." Robertson had spent nearly $80 million "trying to get Cenco up and running." Now, Robertson says, "I'm telling you, it's California, it's environmental, it is just a nightmare." He hopes to recoup some of money by creating "what I hope is the finest industrial park in all of Santa Fe Springs." Thus far, writes Roth, only 22 acres has been sold, for a return of $10 million. All told, Roth concludes, "the Robertson Charitable Remainder Trust has burned through an estimated $78 million of its $109 million starting funds [from the sale of Robertson's International Family Entertainment to Rupert Murdoch's News Corporation] - a loss of 72% of the capital, with no return." "Pat's a very attractive guy to the masses - he really is,'' says Lowell Morse, who oversees Robertson's investments as head of Robertson Asset Management. "He is going to be a more attractive guy, in my opinion, when he's dead. People are not going to realize the impact he had until he's gone." Robertson still has hopes for his gold mine in Liberia. The oil refinery venture in Southern California has turned out to be dismal failure. The quest for immortality, which was supposed to be assured by his business investments, could now be thrust into the hands of the heretofore loyal 700 Club viewers. If after his death they continue to turn on, tune in and dole out money, CBN might survive. Being left in the hands of the capricious clicker-carrying television viewer is not what Robertson had in mind. |

© 1997-2002 BEI

The sexual orientation of individuals pictured in and writers for

Gay Today should not be assumed.

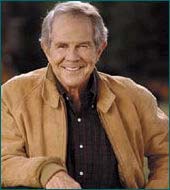

Pat Robertson:

Pat Robertson:  Heir to the throne: Gordon Robertson

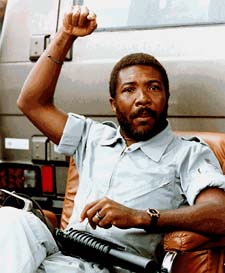

Heir to the throne: Gordon Robertson  Liberian President Charles Taylor, here seen in his days as a warlord

Liberian President Charles Taylor, here seen in his days as a warlord