|

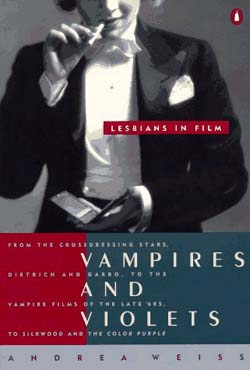

Courtesy of the International Gay and Lesbian Review Vampires and Violets: Lesbians in Film by Andrea Weiss, Penguin Books, 1993, 184 pages, illustrations, index, filmography. (A new retitled version has been published by Pandora Press, Vampires & Violets: Lesbians in the Cinema)  Andrea Weiss's book Vampires and Violets: Lesbians in Film is an assessment of the images of lesbians in narrative films. But rather than cataloging the various appearances of the lesbian in all of her manifestations, whether shrouded in codes and innuendo or out and proud, Weiss is more interested in posing some of the available images (the violet, the vampire) against the overwhelming INvisibility of the lesbian on celluloid. The book is as much about absences as it is about images.

Andrea Weiss's book Vampires and Violets: Lesbians in Film is an assessment of the images of lesbians in narrative films. But rather than cataloging the various appearances of the lesbian in all of her manifestations, whether shrouded in codes and innuendo or out and proud, Weiss is more interested in posing some of the available images (the violet, the vampire) against the overwhelming INvisibility of the lesbian on celluloid. The book is as much about absences as it is about images.

Unlike Vito Russo's seminal (in a double sense) work The Celluloid Closet (1987), which attempted to narrativize and categorize the stages of filmic representations of homosexuality, Weiss's focus is exclusively on the lesbian. Indeed, Vampires and Violets could be thought of as a corrective to the Russo work which dwelled significantly more on the gay male, paradoxically re-enacting in his book the suppression of the lesbian by Hollywood. Weiss is careful to situate her discussions of the films and stars within their proper contexts. This move is productive--she asserts that while Louise Brooks, for example, could dally with rumors of sexual transgression because her persona was based on her ability to shock, Marlene Dietrich's and Greta Garbo's sexualities on the other hand were carefully covered over by studio-constructed star personas. The relative freedom to play with lesbianism in the Louise Brooks case was dependent on lesbianism's ability to further her career within a specific set of parameters: "[Louise Brooks's] sexuality was only another item of curiosity, whereas for the carefully developed star images of Marlene Dietrich or Greta Garbo, public knowledge of their sexuality would have certainly meant the final curtain" (24). This comparison usefully reminds us of the importance of historical situatedness, an argument against those who would point to the Louise Brookses and Clara Bows to suggest Hollywood has NOT been unfair to lesbians. Weiss does not, however, advocate the rejection of Hollywood narratives and stars, despite their limitations. Hollywood and its stars provided an arsenal of images and even strategies for the lesbian viewer: "...the rise of the cinema and especially the Hollywood star system promoted the idea that different roles and styles could be adopted by spectators as well as by actors and actresses, and could signal changeable personalities, multiple identities. This new twentieth-century theatrical sense of self was invaluable to the formation of lesbian identity. If not at the cinema, then certainly through the cinema...such fundamental twentieth-century lesbian experiences as 'passing for straight', crossdressing and masquerade, butch/femme role-playing, gay slang and living double lives, were encouraged and legitimized. In other words, lesbians may have gone to the movies--like everyone else--to find romance and adventure, but they came home with much more" (28-29). Rather than simply lamenting the inadequate representation or the one-dimensional portrayals of lesbians, Weiss is concerned with examining some of the reasons for that invisibility and stereotyping as well as exploring their implications. She asserts that the invisible lesbian has a powerful ideological function: by suppressing lesbian images, the cultural machinery maintains an image of woman as submissive and passive to male dominance.

The lesbian is an Other image that would reveal this particular construct to be a false one; the culture thus colludes to silence the lesbian. Following this argument, the strong lesbian presence in her very absence in Alfred Hitchcock's masterpiece Rebecca is constructed in a way that does not counter male heterosexual dominance--the character Rebecca, who never appears on screen, is figured as a ghostly lesbian who signifies "social deviance, sexual titillation/threat, and boundary against which 'normal' women's sexuality and social role are defined" (55).

The lesbian is an Other image that would reveal this particular construct to be a false one; the culture thus colludes to silence the lesbian. Following this argument, the strong lesbian presence in her very absence in Alfred Hitchcock's masterpiece Rebecca is constructed in a way that does not counter male heterosexual dominance--the character Rebecca, who never appears on screen, is figured as a ghostly lesbian who signifies "social deviance, sexual titillation/threat, and boundary against which 'normal' women's sexuality and social role are defined" (55).

Weiss is careful, however, not to suggest that there are somehow more "appropriate" images of lesbianism that need to be rescued and projected on movie screens. She criticizes the move, made in other gay and lesbian accounts of cinematic representation, of decrying the available images and calling for more positive or accurate ones: "This application of a true or false test to the image suggests that it is sufficient simply to replace the stereotype with a more satisfactory image...It ignores larger problems of representation, by calling for the removal of the offending image but not questioning the ideological processes that gave rise to it in the first place" (63). Through a perceptive analysis of a supposedly "good" lesbian representation in Silkwood, Weiss concludes "In attempting to eliminate the stereotype, Hollywood has also denied the cultural difference [of lesbian and gay identities]. In the process, 'happen to be gay' has become another form of invisibility" (63). Indeed, Weiss argues that grotesque lesbian stereotypes paradoxically provide moments of intense ideological rupture in otherwise idologically seamless Hollywood narratives. By presenting such alarmist visions of supposedly negative behavior and persons, the attempts of the narrative to CONTAIN the lesbian within a heterosexist mode become more visible, providing rich opportunities for constructing oppositional readings (63-64). It seems that the "answer" is not simply putting more or "better" lesbians on screen but examining and exploring the complexities and specificities and contradictions of lesbian lives, as well as considering the possibly positive impact of the supposedly negative images. The chapter on lesbian vampires reflects this position of seeking opposition in outwardly repressive images. The lesbian vampire is "the most persistent lesbian image in the history of the cinema" (84), a fact that demands her serious consideration. The lesbian vampire clearly functions as an embodiment of male heterosexual fear of female sexuality gone out of control; she is always punished and vanquished by the end of the narrative. However, in spite of the inevitable negative outcome for the lesbian vampire, Weiss asserts that she "is the most powerful representation of lesbianism to be found on the commercial movie screen, and rather than abandon her for what she signifies, it may be possible to extricate her from her original function, and reappropriate her power" (104). This reappropriation is precisely what is at work, Weiss argues, when lesbians take control of the vampire film The Hunger by repeatedly using the rewind button of the VCR in order to pull the Susan Sarandon/Catherine Deneuve love scene out of its punishing narrative context and isolate its eroticism and pleasure for positive ends. Weiss also advocates a camp aesthetic for lesbian viewing practices in general, but in relation to lesbian vampire films in particular, for "camp creates the space for an identification with the vampire's secret, forbidden sexuality which doesn't also demand participation in one's own victimization as a requisite for cinematic pleasure" (108). Finally, Weiss interrogates the potential of art cinema for fostering a productive forum for lesbian narratives and images. She finds there that much of the lesbian representations in the art film suffer from the same traps as in mainstream Hollywood cinema: though lesbians tend to APPEAR more frequently in art cinema, "much of this imagery can be problematic and disturbing for lesbian spectators, and tends to convey through images what the Hollywood cinema conveys through absences" (109). This disturbing finding leads Weiss to interrogate the very structures of filmmaking which seem to reproduce this effect. Through analyses of various art film texts, Weiss illustrates how narrative cinema, whether "art" or "mainstream," use the female body and particularly the lesbian body for MEN's visual pleasure. Art cinema is only good as an alternate to Hollywood's treatment of lesbians insofar as it resists these structures. Hence, Weiss demarcates another mode of filmmaking: the independent lesbian film. Lesbian film is characterized by a specific intent to unravel dominant cinema practices that marginalize the lesbian. Perhaps not surprisingly, then, Weiss suggests that it is within the avant-garde and experimental mode that lesbian film is most often successful in dismantling the heterosexual male gaze and heterosexist assumptions more common in narrative and documentary films. Vampires and Violets is an even, thoughtful and useful interrogation of the image of lesbians in film. Although not from a university press, the book weaves together ideas from academic film theory with a real world understanding of how films influence us. Her analyses are subtle and, in some instances groundbreaking, while never sacrificing the book's high degree of readability. The overall approach of Vampires and Violets is refreshing, too Andrea Weiss is not interested in merely trashing the negative lesbian images or privileging the supposedly positive ones. She criticizes the Hollywood versions of the lesbian as well as lesbian filmmakers' versions, and yet at the same time she is willing, unlike other gay and lesbian film critics, to validate the pleasures even in the less savory representations. Vampires and Violets is a necessary and enjoyable companion to other gays-and-lesbians-in-film volumes, and does tremendous work in advancing the discussion to more sophisticated and productive levels. 1998 Review By: Harmony H. Wu Harmony H. Wu is pursuing her doctorate in the Division of Critical Studies in University of Southern California's School of Cinema-Television. Her dissertation is on international horror hybridity and the intersections of genre, gender, sexuality and national identity. Courtesy of the International Gay and Lesbian Review |

|