|

In late 1965 I once sat among stacks of these employees' magazines, astonished, as I flipped through the pages, at the FBI Director's effrontery. Little did I know, as I perused these pictures of Hoover, that his minions-like my Dad-had photographed ME more than once while I marched in that year's picket lines with members of The Mattachine Society of Washington. My dad, fortunately for me, had had little to do with my upbringing. A high school athlete when he'd met Mom and, when I was born, a pitcher-trainee for the Chicago White Socks, he'd returned to Washington following my birth to get a better-paying job, inasmuch as professional baseball in those days paid so little. During World War II he was drafted into the Army and sent to New Guinea. When the war wound down, however, he returned, obtaining a divorce from my Mom, a Scottish-American beauty. At the same time, however, he often took me to watch him pitch for the FBI's Washington office team on Sunday afternoons.

Secret FBI reports, exposed under the Freedom of Information Act, revealed that Hoover and his cohorts had needed a patsy for a murder committed by an FBI mole, and that this innocent man-who had a wife and four children-served Hoover's evil purposes. Congressperson Dan Burton (R-Indiana), as a result, is calling today for the removal of Hoover's name from the FBI's main building in the nation's capital. The congressperson , I must note, is finally on to something. He's inspired me, in fact, to talk about what the late Fred J. Cook titled his mid-60s book: The FBI Nobody Knows. Among the concerns that Fred J. Cook had raised was the nearly pathological fear Hoover inspired among his agents. When the FBI Director was shaking hands with them, for example, he was known to have fired those who had sweaty palms. He distrusted them. As a result, nervous agents stuffed handkerchiefs into their pockets, much-needed sweat-absorbers. While this fact may have seemed inconsequential to others at the time, Cook's reportage struck me as on target. My father's fear of Hoover had indeed been pathological. It ruined much of his life. And it caused him, unfortunately, to threaten mine. In 1960, I'd seen little of Dad since I was ten. He'd been sent to the FBI's Philadelphia office and thereafter to Omaha, Nebraska. His sister, a vicious and delusional hypochondriac, told me that it was because of my gay activism that the Bureau had exiled him to Omaha. I knew this to be untrue, however, because of 35-year-old FBI reports about me kindly retrieved by a media expert, the Professor of Journalism at American University. These reports revealed that my father himself had told his superiors about my gay activism.

I've been quoted in gay history books as saying that my Dad was, like his co-workers, "easily cowed" not only by J. Edgar Hoover, but by "the lunatic ravings of his local Methodist parson." This fact stood out prominently when he realized I was openly gay. He blamed himself for his behavior, even prior to my birth, rattling on about how his divorce from Mom had been a "sin" on his part and theorizing that I was gay because his god was punishing him. "Your odd god works in mysterious ways," I laughed. In 1964, as Vice-president of the Mattachine Society of Washington, I typed a letter from the Society in reply to an FBI request that we cease sending our civil rights publication, The Gazette, to J. Edgar Hoover. In those days I used a pseudonym, having promised Dad to do so until his retirement in two years. Hoover had apparently been made uncomfortable receiving our mimeographed monthly. But the fact that he'd contacted us proved, we wrote the Bureau, that the FBI was maintaining a file on our organization. We agreed to stop sending the publication if only the FBI would first agree to destroy our file and to provide us with the name of a subordinate to whom the publication could be sent. We argued that it was necessary that the FBI be made aware of our civil rights concerns about the treatment of gay men and lesbians at the hands of the U.S. government.

"You mean that I'm your son." "Exactly." "Well, I've been using a pseudonym, as I promised you I'd do until you retired in two years." "But that demonstration at the White House …he's sure to have found out more about you since you did that." "So you heard about it, huh? " I asked. "Word travels," Dad assured me, "and I can't believe you're doing this to me." "I'm doing my best to keep you out of it," I said sympathetically. "Your best isn't good enough," he growled, his tone increasingly agitated. I looked at Lige and realized he too was aware that Dad was behaving oddly. I spoke to him, explaining part of the reason for Dad's agitation. "I'm named after my father," I said, "and he's afraid his job at the FBI will be put in jeopardy because of what we're doing on the gay picket lines." "I know it is in jeopardy," snarled Dad. He became oddly unglued, taking numerous little slips of paper out of his pocket and spreading them across the sofa. Each slip contained the name of one of his relatives. With the entire collection of slips he created a family tree with a branch that led to his name and thence to mine. He pointed angrily to the slip with my name on it. "Our branch ends here," he complained. I tried to show concern, but really didn't feel it. I'd always tried to treat Dad kindly, knowing that neither he nor other members from his side of the family were nearly as bright as my mother's relatives. I'd tried valiantly to ignore the fact that he was a loony fundamentalist, a strict Methodist of the no-dancing sort. Suddenly, however, he turned - right in front of our eyes -into a very scary character. Perhaps I should have anticipated this, although I'd always considered him mild-mannered, thinking he'd be unlikely to wax violent. A peculiar expression crossed his face. "Why don't you and I go to some lonely spot in the country…heh heh heh…and I'll take along my gun," he threatened, patting the revolver in his suit, "and I'll show you how to do some real target practice….heh heh heh." Right in front of Lige I went berserk. I stood up and sounded my own threatening tone: "Look, if you're worried about your Director finding out who I am and what my connection with you might be, just visit me or call me again, and you can be sure he'll find out!" Dad looked stunned. I continued: "I'm telling you now, don't ever come around me again. I never want to see you or hear from you again." He turned, the peculiar expression still written on his brow, and stormed out the door. "Do you think I was too harsh?" I asked Lige. "He was threatening your life," Lige replied.

In fact, as I said, the Director got his earliest information about my Mattachine Society identity (even though his agents had taken pictures of me on the picket lines) from Dad himself, some six months following his final visit to my house. Dad must have struggled with his worries about what I might reveal, and had decided to get the jump on me. When editing GAY (1969-1973) Lige and I had heard mysterious clicks on our phone but had simply ignored them. "We mustn't be paranoid," we told ourselves. In l ater years, after Lige was gunned down at a mysterious roadblock-I've often wondered whether my Dad or the FBI could have had something to do with his murder. There had been talk of CIA involvement too. But there's been no way of knowing who had set up the roadblock and pulled the trigger. Dad, at the time Lige was killed, had already been retired. Together-between 1965 and 1975-- Lige and I had written many bold tirades against Richard Nixon and other Republican ghouls. We'd also commissioned an interview with Vice-president Spiro Agnew's son, who'd been suspected by a prominent pundit of being gay because he lived with a hairdresser. We'd published dorky, scowling photos of Nixon on the cover of GAY with headlines like: "Nixon Opposes Gay Marriages". Could the GOP goons have struck back? In any case, news of FBI incompetence prior to the bombing of the World Trade Center simply renewed for me what I'd known for decades: the Bureau is full of frightened intellectual drawfs, not unlike my father who toiled for J. Edgar Hoover for 25 years, never realizing, of course, that he was working for "Mary." |

|

© 1997-2002 BEI

The sexual orientation of individuals pictured in and writers for

Gay Today should not be assumed.

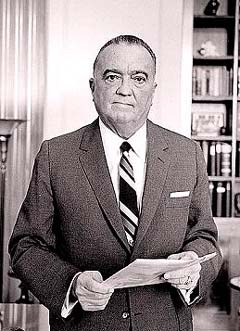

J. Edgar Hoover: FBI chief and cross dresser

J. Edgar Hoover: FBI chief and cross dresser  Jack Nichols and his father, "Dick"

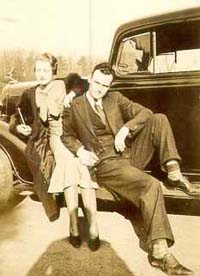

on a downtown Washington, D.C.

street during World War II

Jack Nichols and his father, "Dick"

on a downtown Washington, D.C.

street during World War II  Jack Nichols' parents, prior to his birth

Jack Nichols' parents, prior to his birth  Jack Nichols' father, John Richard Nichols,

with his friend Walter Johnson, Jr., a

son of the famed baseball star, in 1935

Jack Nichols' father, John Richard Nichols,

with his friend Walter Johnson, Jr., a

son of the famed baseball star, in 1935  Jack Nichols and

Jack Nichols and