|

Media Matters

As a historian, though, what I find perhaps even more remarkable is the larger perspective that evolves from, first, recalling how The Times treated gay people in the not-so-distant past and, second, examining the forces that played a role in the change coming about. I can still remember the chill that ran down my spine the day that I, sitting at a microfilm reading machine at the Library of Congress, saw the headline on a front-page story that had appeared in The Times in 1963: "Growth of Overt Homosexuality in City Provokes Wide Concern." Ouch. The final word in the headline-"Concern"-alerted me to what was to come. And the first paragraph, unfortunately, showed that my instincts were correct: "The problem of homosexuality in New York became the focus yesterday of increased attention by the State Liquor Authority and the Police Department." I once again cringed, this time at the word "problem." (If there was a "problem" related to people being gay, I told myself, it was with society's response to gay people-not with homosexuality itself.) But statements later in the story sent the same objectionable-and patently incorrect-messages: "The old idea, assiduously propagated by homosexuals, that homosexuality is an inborn, incurable disease, has been exploded by modern psychiatry, in the opinion of many experts. It can be both prevented and cured, these experts say." In the 1970s, gay activists began to make inroads toward harnessing their potential voting power into a political force, but The Times did its best to obstruct that effort. When the Gay Activists Alliance in the nation's largest city succeeded in persuading three candidates for elected office to endorse a gay rights platform, it was a major triumph. Nevertheless, the paper buried the story at the bottom of page 36.

Because of the many social, political and cultural changes that have taken place between the 1960s and today, it would be simplistic to point to any single event or individual as the only one that caused the most influential newspaper in the country to improve how it treated gay people and issues. If an informed observer were looking for such a force, however, one candidate would be a private lunch two men had in 1981. Arthur Sulzberger Jr. had begun asking a select number of Times reporters and editors to meet one-on-one with him. "Arthur Junior," as many people called him, was the son of Arthur Ochs Sulzberger and was being groomed to take over his father's position of publisher. The first of the staff members that the publisher-in-training asked to lunch was Jeffrey Schmalz, an editor Sulzberger had come to know while working on the metro desk. Halfway through their meal, Sulzberger turned to Schmalz and asked: "When are you going to tell me you are gay?" Schmalz was startled at the question, partly because of its directness and partly because he thought that he'd succeeded, during the several years he had worked at The Times, at keeping his sexuality a secret. The editor decided it was finally time to tell the truth. "I am," Schmalz responded. "What do you want to know?" Sulzberger said he didn't have any particular questions but wanted to assure the editor that "things will get better" at The Times-both in how gay employees were treated and in how gay issues were covered. That brief exchange of words became much more poignant in December 1990 when Schmalz, by then having been promoted to deputy national editor, collapsed on the floor of the newsroom. Doctors told the editor that he had suffered a grand mal seizure, that he would need brain surgery, and that he had AIDS. In early 1992, Schmalz returned to The Times after having the surgery and spending a year recuperating. And a few days later, Sulzberger became publisher. "The difference was like night and day," Schmalz said about the Times's approach to gay coverage. "I think that as he [Sulzberger] gained in power, the paper more and more took the right stand on gay employees and gay issues." Dramatic evidence of how much the paper had changed came when Schmalz, no longer physically capable of being an upper-echelon editor, was assigned to write about AIDS. Being named to that position was significant, as conventional thinking in the journalism world was that a reporter should not be allowed to cover a topic in which he or she has a personally involvement. Schmalz soon showed the fallacy of that concept, producing stories about the disease that were far more insightful and far more powerful than anything than an "objective" reporter could have written. In an article headlined "Covering and Living It: A Reporter's Testimony," he wrote in December 1992: "Two years ago tomorrow, I collapsed at my desk in the newsroom of The New York Times, writhed on the floor in a seizure and entered a world of AIDS." Schmalz opened that world to his readers by, for example, describing a conversation that he had while attending the funeral of a man who had died of AIDS. Schmalz wrote that he had been asked, "'Are you here as a reporter or as a gay man with AIDS?'" When he responded that he was there as a reporter, he wrote, "Some shook their heads in disgust, all but shouting 'Uncle Tom!' They wanted an advocate, not a reporter." During the early 1990s, Sulzberger and Schmalz also both played important roles in the formative stages of the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association. "I'm convinced that if newspapers are to survive, they can no longer be exclusionary bastions of a single view of the world," the publisher told the NLGJA's first convention. "Only when we offer our readers a wide spectrum of viewpoints can we say we are fulfilling our role as journalists. We need to find the courage to cover the world the way it is. We must offer our readers coverage of the broad gay community, its people, and its issues." Schmalz followed in his boss' footsteps by giving the keynote address for the association's second convention in September 1993, speaking to his gay and lesbian colleagues as an openly gay journalist with AIDS. "I actually came very late to this fight and have borne an incredible guilt complex because of that," he said. "I'm sorry, and I'm very grateful to you for having borne that fight for so long." Five weeks later, Schmalz died. He was 39. By no means can I draw a direct, cause-and-effect line between two events that are separated by more than two decades-the 1981 lunch between Arthur Sulzberger Jr. and Jeffrey Schmalz, and the recent decision by The New York Times to publish same-sex commitment announcements. And yet, I believe that those of us who are pleased with the historic policy shift by America's leading newspaper owe a debt of gratitude to two men-one straight, one gay-whose courage has made a noteworthy difference in our world.  Rodger Streitmatter, Ph.D. is a member of the School of Communication faculty at American University in Washington, D.C. His latest book, Voices of Revolution: The Dissident Press in America has just been published by Columbia University Press. He is also the author of Unspeakable: The Rise of the Gay & Lesbian Press in America (Faber & Faber, 1995) and Raising Her Voice: African American Women Journalists Who Changed History (The University Press of Kentucky, 1994)

Rodger Streitmatter, Ph.D. is a member of the School of Communication faculty at American University in Washington, D.C. His latest book, Voices of Revolution: The Dissident Press in America has just been published by Columbia University Press. He is also the author of Unspeakable: The Rise of the Gay & Lesbian Press in America (Faber & Faber, 1995) and Raising Her Voice: African American Women Journalists Who Changed History (The University Press of Kentucky, 1994)

|

© 1997-2002 BEI

The sexual orientation of individuals pictured in and writers for

Gay Today should not be assumed.

When The New York Times recently announced that it will begin publishing announcements of same-sex commitment ceremonies, the gay and lesbian community was jubilant-and rightly so. The most prestigious news organization in the country acknowledging that two men or two women entering into a substantive relationship is just as newsworthy as a man and a woman getting married, yes, that is most definitely a step worth celebrating.

When The New York Times recently announced that it will begin publishing announcements of same-sex commitment ceremonies, the gay and lesbian community was jubilant-and rightly so. The most prestigious news organization in the country acknowledging that two men or two women entering into a substantive relationship is just as newsworthy as a man and a woman getting married, yes, that is most definitely a step worth celebrating.

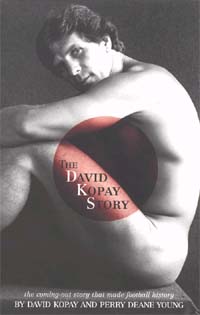

When David Kopay wrote his autobiography, The New York Times met it with a homophobic review

When David Kopay wrote his autobiography, The New York Times met it with a homophobic review