|

|

|

David Carter on Allen Ginsberg |

|

Interview By Raj Ayyar

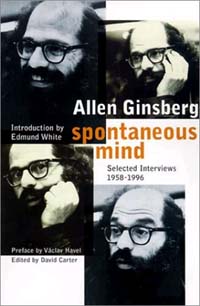

After all, he was the imp royale of the Beat movement, a latter-day Jewish prophet thundering against the evil, machine-like bureaucracy that stifles creativity and oppresses the Other in America and elsewhere, the gay poet who was out about his sexuality when so many of his contemporaries were cowering in their closets, and the spiritual seeker extraordinaire who tried to fuse spirituality and sexuality, thereby dragging William Blake and Walt Whitman into the 20th century and well beyond. David Carter's Spontaneous Mind (Harper Collins, 2001) is a real labor of love that brings together selected Ginsberg interviews and presents them so that we can hear Allen's own voice just as if he were having his own personal dialogue with the reader. Interviewing David was a real treat for me. Throughout our richly textured if brief interview, I felt Allen's presence between us, a tender shade, laughing, mocking, loving, intrigued, nude and hugely enjoying this jam session. Raj Ayyar: David, these questions are in the nature of jottings on bar napkins, poetic prompts and philosophical teases, much in the spirit of Ginsberg himself. David Carter: (laughing): Okay. Raj Ayyar: That way, we can take off and improvise whichever way the spirit leads us. I want to tell you how much the book has revitalized me at a time in my life when I was going through a "multiple blues" phase----blues about Dubbya and God's Own Party, personal and professional crises and collapses and so on. When I read Spontaneous Mind, I wanted to dance, sing, primal scream the blues out of my body and to cry. It brought back memories of my own involvement with the Beat movement back in the '70s. I stayed up all night, calling a friend and talking her ear off till 6:00 a.m. and reading Ginsberg's lines aloud on the phone in bebop rhythm.

David Carter: You know, it's interesting that you should say that. A number

of readers have said that the book has changed their lives. You see, Allen

saw the interview as an art form, a teaching tool and as a way of touching

people across time and space. In fact, he believed that the interview was a

mode of transmitting the artist's consciousness through time, even beyond his

own death.

David Carter: You know, it's interesting that you should say that. A number

of readers have said that the book has changed their lives. You see, Allen

saw the interview as an art form, a teaching tool and as a way of touching

people across time and space. In fact, he believed that the interview was a

mode of transmitting the artist's consciousness through time, even beyond his

own death.

Raj Ayyar: Tell us about your own relationship with Allen. David Carter: I first met him about '74 or '75, when he gave a reading at Emory University. The reading was done soon after Dylan had just finished a tour after not performing for many years. At the reading Allen said that he had noted that on the tour Dylan had sung much of his earliest material, inspiring him to do the same, so that I was fortunate to hear Allen read Howl the very first time I heard him. You probably also know that Dylan learned a lot from Allen, who first turned him on to Emily Dickinson and Rimbaud among others. Raj Ayyar: I recall Dylan once describing Ginsberg as "a lyrical genius, a con man extraordinaire, and probably the greatest single influence on American poetical voice since Whitman." David Carter: Yes. Getting back to my relationship with Allen, I ended up interviewing him for a gay cable TV show in Wisconsin called 'Nothing to Hide.' This was in the early '80's. Although I did not know Allen well personally, he was always generous toward me and supportive, and I consider him one of my mentors. Raj Ayyar: How did the idea of Spontaneous Mind come about? David Carter: As early as 1992, I had conversations with Allen's secretary, Bob Rosenthal, about editing Allen's interviews into a book. Allen had given hundreds of interviews and was keen on a volume that would bring the best of them together. Allen gave the project his blessing and support and by the time I finished the final draft of Spontaneous Mind, I had a collection of 352 interviews in print form. Raj Ayyar: David, it's a true labor of love. You can hear Allen's voice in print form and that's no mean accomplishment. Isn't it true that part of Allen's uniqueness in the Beat movement was that he was an ongoing critic of political and cultural oppression? I mean, none of the other Beat writers could lay claim to being as consistently political as Allen. His work challenges bureaucracies everywhere, attacks the American war machine and challenges homophobia, sexism and racism in various contexts. David Carter: I think that Allen was first and foremost a great artist who naturally brought his artistic sensibility to bear upon political and cultural issues-or anything else he was considering for that matter-so what we get is not inferior art as political commentary but a great artist addressing himself to the injustices and oppression of his time. Thus the critique is a manifestation of his art, not the other way around.

Raj Ayyar: What about 'carezza', so beloved of Carpenter and Whitman, men lying together and being tenderly affectionate without 'doing' anything? Doesn't Ginsberg say that he was content with this on some occasions and with 'ethereal' orgasm, particularly in his impotent phases? David Carter: Ginsberg did sometimes practice carezza when another male had an open heart but, being heterosexual, did not want to have genital sex with Allen. But you've got to remember that Allen was sexually active almost to his dying day! In fact, he was surprised to learn of his HIV-negative status when admitted to the hospital just before his death. He said, "That's surprising because I've been getting a lot lately!" Raj Ayyar: I recall a passage in Footnote to Howl, where Allen says 'Holy! Holy! Holy! The world is holy! The skin is holy! The tongue is holy! The tongue and cock and hand and asshole holy!' This is a clear harking back to Whitman's Song of Myself. And in Kaddish he speaks of Matterhorns of cock, Grand Canyons of asshole.'

David Carter: Undoubtedly. His honesty, courage and sense of principle permeate his life and work. Which is why there is a sense of congruence and continuity about all the decades of his work. He was someone who was always alive to the present instead of beating the same old drum for 30 years, which is one of the reasons that the evolution of his thought is genuine, organic, and has integrity. Raj Ayyar: Going back for a minute to his gayness, Allen was never darkly conflicted and self-hating about his sexuality as Jack Kerouac was. David Carter: Kerouac suffered from deep internalized homophobia. When he was at Columbia, he and his fellow football jocks would go out on gay bashing sprees. Yet, Kerouac slept with a number of men, including Allen. Raj Ayyar: And Allen had sex with Cassady and Burroughs as well, right? David Carter: Yes.

David Carter: I think there was a small part of Allen that enjoyed shocking the prudish middle class, but I do not think that his openness about his body and his sexuality came mainly from that part of him but rather from the visionary in him. Remember that Allen believed that most people in the modern world, and especially the white Western world, live too much in their heads. Moloch was the Blake-like symbol that he used to describe cut-off people who lived inside their minds. Whereas, the body, by contrast, is connected with heart and feeling and needs to be expressed and celebrated. Raj Ayyar: Surely by 'Moloch', you don't just mean 'mind.' Aren't we talking about industrial and post-industrial mind, corporate-oppressive mind? Similar to Blake's 'Urizen'---- that evil machine rationality of the capitalist system? Work-obsessed, hyper-rational, techno-productive, materialistic mind? David Carter: Yes, Allen made clear that he was in no way opposed to the use of reason, it was the exaggerated use of reason that he took a stand against. In other words, reason as perversely used in the modern world in a way such that reason always trumps feeling, intuition, and sensation. Moreover, Moloch isn't simply capitalistic in Allen's work. All the Communist countries that kicked him out like Cuba and the old Czechoslovakia were in the grip of Moloch, as could also be said as well about the worst forms of organized religion. Raj Ayyar: You know, Allen speaks of Blake as a neo-Gnostic. Any comments? David Carter: I think that by the word 'Gnostic' he means not just the Christian heresy that was persecuted by the church since the time of Constantine, but a spiritual outlook that is holistic, not organizational or hierarchical, that finds the divine within and around us and in the lived body rather than as some pie-in-the-sky cosmic potentate 'out there.' It's interesting that Allen was very drawn to devotional Hindu and Catholic mysticism early on and moved to a Vajrayana (Tibetan) Buddhist position in his later years. He was a tireless spiritual explorer and knew and worked with an impressive number of spiritual teachers including Swami Prabhupada of the Society for Krishna Consciousness, Swami Shivananda, Swami Muktananda, and Chogyam Trungpa, to name a few. Raj Ayyar: There's been much talk of 'gay spirituality' in recent years. I don't mean the tired-ass quest for a gay-safe Jesus, but alternative forms of gay spirituality. I'm thinking of the tradition from Ram Das to Mark Thompson, Judy Grahn, Toby Johnson and others. Do you think Ginsberg was a pioneer here?

Raj Ayyar: Yet he enjoyed hangin' out with common folk whether at Vesuvio's in North Beach, San Francisco or drinking cheap liquor with the homeless under the Howrah bridge in Calcutta. In our own alienated, touch-phobic, e-mail insulated age, we seem to have lost the flair for real connection with others. David Carter: We do appear to have lost the knack for just hanging out. In fact, David Amram, American French horn player and classical and jazz composer said once that the Beat writers all got PhDs in 'hangoutology.' Raj Ayyar: Tell us a little about your upcoming book on Stonewall. Why Stonewall? David Carter: Stonewall is a mythic symbol for the gay community. (I'm using the word "mythic" in its original sense of a powerful story, not the modern vulgar sense of "a lie.") I've always been fascinated by and drawn to Stonewall myself. When I read Martin Duberman's book on the subject I was struck by how brief the account of the riots was. I then found out that there were many sources available that he had not used, so I realized that the full story had not yet been told and felt that there was still a chance to tell it. I have been working on this book for eight years now and am just finishing the first draft to deliver to Michael Denneny, whom I feel very lucky to have as my editor at St. Martin's Press. People are always saying they want to know what really happened at Stonewall: well sometime in 2003 they will, for this account is very detailed. For example, three chapters of the book are devoted to just the first night of the riots. I also found a lot of new and interesting material about the origins of the gay liberation movement. Raj Ayyar: David, Allen assures us that "if we talk to people as if they were future or present Buddhas, then any bad karma coming out of it will be their problem rather than yours." Since we've both been treating each other at a Buddha level, I'm sure the interview will turn out fine! David Carter: Raj, it's been a pleasure chatting with you. Raj Ayyar: Likewise, David. She ba zha zee bop do me na za du ma jee, boo da boo.... Or as Allen would say, "Ahhhh..." Just breathe. |

© 1997-2002 BEI

David Carter

David Carter  Raj Ayyar

Raj Ayyar  Allen Ginsberg

Allen Ginsberg