|

|

|

By Jack Nichols

The little-known Marfan syndrome surfaced momentarily when Larry Kramer raised the issue of Abe Lincoln's sexuality last year. If one knows of men or women who seem to fit into Lincoln's particular physical category, it follows that being conscious of the Marfan syndrome can make us sophisticates in our approaches to our brothers and sisters who live within it. The little-known Marfan syndrome surfaced momentarily when Larry Kramer raised the issue of Abe Lincoln's sexuality last year. If one knows of men or women who seem to fit into Lincoln's particular physical category, it follows that being conscious of the Marfan syndrome can make us sophisticates in our approaches to our brothers and sisters who live within it.

The syndrome raises significant questions about Madison Avenue's tyrannies, those perpetuated by its commercially-propelled ventures, its pushy product-marketings with their unrelenting focus on conventional concepts of beauty. What sorts of unhappiness does this "ideal" focus cause for vast numbers who remain outside its narrowly specified perimeters? Dr. George Weinberg, the pioneer who coined the word "homophobia," indicated in 1974 how he'd felt it necessary to rebut "the criteria of physical beauty according to which all but one person in ten thousand is ugly." Dr. Weinberg's classic statement, celebrating more highly-developed aesthetic tastes, said that: "The art of life consists largely in the ability to see beauty, to remain open to beauty, for nature never tires of showing it to us in new forms." A half-century ago, when gay men and lesbians often had good reason to feel hopelessly excluded from the human community, Donald Webster Cory wrote in The Homosexual in America: "The homosexual, cutting across all racial, religious, national and caste lines, frequently reacts to rejection by a deep understanding of all others who have likewise been scorned because of belonging to an outcast group. 'There but for the grace of God…' it is said, and the homosexual, like those who are part of other dominated minorities can 'feel' as well as understand the meaning of that phrase.

Now that social integration for same-sex lovers is on the horizon, the importance of what Donald Webster Cory said in 1951 must never be forgotten. It throws an immediate light on the little-known Marfan syndrome today. We're learning, as candidate Al Gore recently and eloquently put it about gay men and lesbians, that America is about to "expand the circle of human dignity yet again." Further expanding the circle-- to include people of all types. Eugenics enthusiasts would solve the Marfan syndrome and the problems raised by our culture's approach to appearances by recommending genetic tinkering in lieu of plastic surgery.

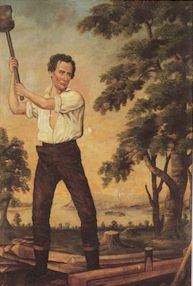

"In my early school years, I was at war with the disorder. Taller and skinnier than my classmates, I felt a fish out of water, especially when standing in line. I desperately wanted to be like other kids. The muscles behind my head tended to tire easily. When they did, the ligaments were unable to prevent the head from nodding. "Children witnessing the nodding were merciless in parroting me; smirking as though what I did were some kind of joke. Humiliated, I felt more alienated than ever. "My poorly constructed ligaments prevented me from participating fully in gym. Limited in my fielding and throwing ability, I purposely remained out of the limelight of the game, praying the sport would pass me by. When I did play, the opposition always scored." Before his last year in elementary school, the youngster's body became stronger, thus alleviating the head nodding and, although he was still taller, he was closer in size to his classmates. But despite these physical changes, his self-esteem remained low. Social events were painful. He was convinced that his narrow face and his lack of conventional coordination would cause people to laugh and point if he entered a room. During the summer he turned fifteen, however, he toured a museum dedicated to Abraham Lincoln. The tour changed his life. Having admired the sixteenth president, he found the museum artifacts interesting. But what had really caught his eye was a life-sized silhouette of Lincoln painted black on a wall of the room. Wondering if his own elongated limbs and short upper body might fit into the former President's shadow, he stood up against it and found that he was a perfect match.

Many young gay males and lesbians today can still identify with the cruel ostracism this young Marfan syndrome person felt. Some of us are in a position to do something—through friendships, through counseling, through the arts. There is now a web site devoted to persons with the Marfan syndrome. We can learn more about those who live within this syndrome, and thus be prepared to lovingly embrace them when they cross our paths. |

© 1997-2000 BEI

Dr. George Weinberg

Dr. George Weinberg