|

|

|

(1951-2002) By Perry Brass

I remember Sylvia from my time in the Gay Liberation Front, right after Stonewall in 1969. I was twenty-two then, and people like Sylvia amazed and scared me. A beak-nosed, teen-aged street queen, thin as a scarecrow, who appeared more like a tough Puerto Rican boy with a 5 o' clock shadow, in drag; she was all balls. She had a sharp, cigarette-edged voice that could cut through walls of bullshit. She had been hustling since she was ten, sleeping in poor neighborhoods in New Jersey or Brooklyn or on the streets of the Village, and she had brain like a stiletto: it thrust right to the point. She used to ask, "Why are the dykes so afraid of us drag queens?" because the P.C. GLF women felt that drag queens were "appropriating female" dress, but still had "male privileges." The only privileges Sylvia had were breathing, not getting beaten up, and making a little money from "straight" johns in exchange for a blow job in the back seat of a car.

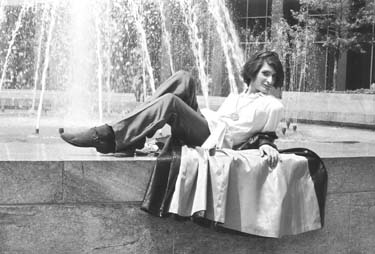

Sylvia Rivera, 1970

Sylvia Rivera, 1970 Photo By: Kay Tobin Lahusen I remember when I was twenty-three being out on Christopher Street in the Village late one night, and seeing Sylvia snap the neck of a Budweiser bottle off on a sidewalk to go after a customer who had thrown one of her girlfriends out of his car. Three queens ran after him as he tried to drive down the street and I decided that you didn't fuck with these girls: they came from an even wilder part of the queer woods than I, who grew up in a public housing project in Savannah, but read E.M. Forster, did. You had to be fearless to survive here. I respected that. They knew that the alternative to this life was just death, which made the Stonewall riots make sense.

I don't think that Sylvia ever really wanted "equalty." I think that what she wanted was not to feel so alone, so threatened, and to have her friends with her. Her friend Marsha P. Johnson, another "lady of the night," black, who had started out as a boy, was murdered ten years ago, and her body was found in the Hudson River. The cops in the Village, after ignoring the crime at first, refused to classify Marsha's murder as a bias crime. It was simply the death of another disposable thing; like the death of a stray cat. Marsha had also been an early pioneer of the gay movement, but she could never get off the street. I would give her money when she was panhandling in the Village and she would smile at me and say, "Hi, Perry," and we would talk as other people ignored her. She became an embarrassment to my polite queer friends, someone we did not know where to place. If she had been white and English, she would have been Quentin Crisp, but she was black and impoverished. Marsha was a sweet, simple, polite person, but Sylvia was much more complicated and intelligent. She had a lot of real wisdom in her, but there was that problem of having to escape what she was-those ghosts of a past that don't leave us easily-but maybe she should not have had to escape it entirely. She hit rock bottom several times, addicted to drugs and vodka, living on the rotting piers that used to line the West Village. Then she managed to clean herself up, and she worked in Randy Wicker's store on Hudson Street near Christopher that sold lighting fixtures.

Mostly what she talked to me about was the hell of being young, gay, and poor. These were things that did not change: the loneliness, the isolation; being rejected from families, living on the street. I remembered a poem that she wrote and published in the GLF paper, Come Out!, when she was an 18-year-old kid and finally people would listen to her. It began, "Do you know the loneliness of the gay life?" I think that is what struck me so much about her all the years that I knew her. That real sense of loneliness that she had that was so out there, so open, that I could not even touch it. Queer men for the most part abused or shunned her; women were scared of her or revolted by her. Her friends were other queens, or a few people who stuck by her. Randy treated her like a regular person. They would fight-she could be incredibly bossy; he really loved her. A few years ago, she found a lover, a young, very shy, pale-skinned woman named Julia Murray, and I remember Sylvia saying to me, "I just can't deal with men anymore. I've thought about having the operation and becoming a lesbian, but I really like myself the way I am." She would look at me with her very intense dark eyes as she talked, and I have to say that I liked her the way she was, too.  Perry Brass's newest novel is WARLOCK, A Novel of Possession,

that does deal with the interesting intersection of business and evil.

His "domestic partnership" is not underwritten by any of the Fortune 500.

He can be reached through his website www.perrybrass.com. For more information

on WARLOCK, go to http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ ASIN/1892149036/107-8161877-7587701

Telephone: 1 (800) 365-2401.

Perry Brass's newest novel is WARLOCK, A Novel of Possession,

that does deal with the interesting intersection of business and evil.

His "domestic partnership" is not underwritten by any of the Fortune 500.

He can be reached through his website www.perrybrass.com. For more information

on WARLOCK, go to http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ ASIN/1892149036/107-8161877-7587701

Telephone: 1 (800) 365-2401.

|

© 1997-2002 BEI

Sylvia Rivera at the True Spirit Conference

Reception in Washington D.C., February 16, 2001

Sylvia Rivera at the True Spirit Conference

Reception in Washington D.C., February 16, 2001  Sylvia Rivera at the Greenwich Village shop of Randolfe Wicker

Sylvia Rivera at the Greenwich Village shop of Randolfe Wicker