|

|

|

|

|

By Rex Wockner

I was in the midst of re-reading his 1973 novel Forgetting Elenawhen I got word he was passing through San Diego 12 hours later. We chatted on a deck in a parking lot behind the gay bookstore Obelisk in San Diego's Hillcrest district. Rex Wockner: The last time I interviewed you, 12 years ago, I was too young and dumb to be intimidated. Now I'm older and I'm intimidated. Edmund White: Don't be. My God. Rex Wockner: I bet you haven't seen the new issue of Genre yet. I got a Fed-Exed copy yesterday. Your Dad smoked cigars and you hated that and you hated him. Then you had this master and the first thing he would do when he got to your house [White laughs loudly] is light up a cigar. Edmund White: Oh, I remember that interview.

Rex Wockner: You've returned to America after 15 years in France. How does the gay world of Paris differ from the gay world of major U.S. cities? Edmund White: Most gay people in Paris don't live in the ghetto and are not easily identified as gay. They don't live in a gay neighborhood, they don't dress in a recognizably gay way. You meet somebody through straight friends of yours who is young and unattached, and you see him half a dozen times and then one day he says, 'Oh, yes, I'm gay, didn't you know that?' It never comes out in a kind of real obvious way. It's much more discrete. And I would say discrete rather than closeted because I don't think they're really closeted, I just think they have this don't-ask-don't-tell policy in general and gays are much better integrated into the straight community and they all have a lot of straight friends. It would be rare to go to a party in France of all men. Very rare. It'd be much more likely to go to a party where there were a lot of straight women and gay men but everybody is flirting with everybody. Rex Wockner: I read an interview a long time ago where you said that some bathhouse you wanted to go to in Paris wouldn't let you in because of your age but then you found a bear bathhouse. Edmund White: I did. It's a great one... way out in Vincennes which is kind of a family neighborhood ... near a big park that's built around a military barracks. In the town of Vincennes, which is the last stop on the subway line, is this bath, which is pretty extraordinary. I mean, there are guys of all ages and then there are young people who admire them. Rex Wockner: You told Genre you're having more sex than ever with younger guys these days because either you can buy them or they want to sleep with a famous writer. Edmund White: [He laughs.] I think I was bragging. That interviewer kind of wound me up. Rex Wockner: It reads that way. Edmund White: He was very cute, very impertinent, and I think I just sort of took the bait. I kind of went crazy in that interview. The whole time I was giving that interview I was thinking, my editor is going to crucify me for this. Rex Wockner: You're back in New York now. How has it changed in the 15 years you were gone?

Edmund White: It's less bohemian. I can remember meeting an awful lot of

people in the arts who were gay who were quite serious and kind

of nerdy looking -- which is sort of one of my types, I mean I

like nerds -- and now they're all so buff and so perfect and

materialistic, I think. ... It is amusing. I like to go to The

Big Cup [in Chelsea] and hang out there. ... I'm 40 years older

than anybody else in there but still I will sometimes meet people

who don't know who I am and we'll just be sitting at the same

table drinking our lattes and we'll start talking. And of course,

the generalizations I'm making are only about the surface look of

people. When you dig deeper, you always find that people are

quite interesting and very different, one from the other.

Edmund White: It's less bohemian. I can remember meeting an awful lot of

people in the arts who were gay who were quite serious and kind

of nerdy looking -- which is sort of one of my types, I mean I

like nerds -- and now they're all so buff and so perfect and

materialistic, I think. ... It is amusing. I like to go to The

Big Cup [in Chelsea] and hang out there. ... I'm 40 years older

than anybody else in there but still I will sometimes meet people

who don't know who I am and we'll just be sitting at the same

table drinking our lattes and we'll start talking. And of course,

the generalizations I'm making are only about the surface look of

people. When you dig deeper, you always find that people are

quite interesting and very different, one from the other.

It's sort of interesting to be at the red-hot center of the movement even if you feel out-of-sync with it. My boyfriend who's in there [in the bookstore] is 35 -- and he's a very young- looking 35 -- and he feels quite alienated from that whole world too because he's a writer and he'd rather spend his time writing than going to the gym, so even though he has a nice natural body he's not a brontosaurus. Rex Wockner: It looks like you still haven't had to take any HIV drug cocktails. Edmund White: That's right. Rex Wockner: It's been, what, 15 years or more? Edmund White: I was diagnosed in 1985. I'm supposed to be something called a long-term non-progressor. Rex Wockner: You still have normal CD4 cell counts? Edmund White: I haven't even had them tested in a year but the last time I looked they were like high 600s. Rex Wockner: That's great. That's like the lower end of normal. Edmund White: I feel lucky. I don't take any credit for it at all. I don't drink. I don't smoke, and I sleep a lot, but I don't think that has anything to do with it. I think it's genetic. I'm awfully happy to have been granted this reprieve because I feel like I've been able to write a lot of books. From the time I saw you [in 1988] till now I've written God-knows-how-many books. Rex Wockner: I just found out today you were going to be in town. I'm actually re-reading Forgetting Elena right now. It's in my backpack. The detail in that book still blows me away, the detail of the things that pass through our minds so quickly before we make a decision or a judgement. Edmund White: It's a very close focus on inner processes, isn't it? It's written in the present tense, which a lot of people don't even notice, because that, I think, adds to that feeling of getting a mind at work second-by-second. Rex Wockner: Have you read it in the last 10 years? Edmund White: No. I'd sort of like to. Rex Wockner: How did America strike you coming back after being gone for so long?

Edmund White: A lot of great things. One of the advantages of a thriving

economy is that everybody is moving up, or seems to be, in the

world. I mean, the man who drove us down tonight, he's from Chile

but he's studying to get his MBA. In France, somebody's who's

your chauffeur would probably be a chauffeur for life, that is

what he would do. Same thing with a waiter. Waiter is a

profession in France and people do it their whole lives. Here

most waiters, if you tease them a little they drop their formal

manner and are just guys. And if you talk to them -- you can

talk to them, first of all; they don't hide behind a professional

mask as they do in Europe. Secondly, once you dig a little bit

deeper you find out that they're studying art history or are in

pre-med or something like that. There's a tremendous climb

upwards in this society which is very exciting actually. People

are very optimistic here, and cheerful, I think. Sometimes

they're stressed out because they're overworking. But there is

this kind of optimism which I knew when I was a kid in the

fifties and in the early sixties but which vanished really from

America -- especially New York which went through a period of

bankruptcy and danger and crime in the seventies and then the

recession in the eighties. This is one of the high points now in

American history and I think people should be aware of it.

Edmund White: A lot of great things. One of the advantages of a thriving

economy is that everybody is moving up, or seems to be, in the

world. I mean, the man who drove us down tonight, he's from Chile

but he's studying to get his MBA. In France, somebody's who's

your chauffeur would probably be a chauffeur for life, that is

what he would do. Same thing with a waiter. Waiter is a

profession in France and people do it their whole lives. Here

most waiters, if you tease them a little they drop their formal

manner and are just guys. And if you talk to them -- you can

talk to them, first of all; they don't hide behind a professional

mask as they do in Europe. Secondly, once you dig a little bit

deeper you find out that they're studying art history or are in

pre-med or something like that. There's a tremendous climb

upwards in this society which is very exciting actually. People

are very optimistic here, and cheerful, I think. Sometimes

they're stressed out because they're overworking. But there is

this kind of optimism which I knew when I was a kid in the

fifties and in the early sixties but which vanished really from

America -- especially New York which went through a period of

bankruptcy and danger and crime in the seventies and then the

recession in the eighties. This is one of the high points now in

American history and I think people should be aware of it.

There's a down side which is a kind of dumbing-down of America, a kind of triumphalism that Americans all feel -- that they are the best and the most -- which brings about a kind of chauvinism, I think, a lack of interest in other cultures. In the gay world, gay culture is sort of floundering at the moment, I think, in a way. A lot of gay bookshops are having trouble hanging on. In France there's a special law that you can't discount books, so the big stores can't discount books. All they can offer is more books. That means that there are more bookstores in Paris than in all of America. Every little bookstore is preserved because they can sell books as cheaply as the big store. It's sad to see the death of so many gay bookstores which have been something like a community center for gays; in many towns, that is the community center. Rex Wockner: Is France less materialistic or consumeristic? Edmund White: I think so, especially in the arts. What America used to have and France still has is a group of young people who don't make much money and don't expect to ever make much money and all they desire is excellence in the arts. Here there's no tradition of honorable poverty left. Poverty's always sort of despicable now in America. There's very little of that old bohemian spirit that would say, 'Well, you're a great artist and you have ten loyal followers and that's enough.' Now everybody wants to have the movie version and the house and the second house and the yacht and whatever. That's the only way that people can really measure excellence now. Rex Wockner: I think the gay movement in this country has won the war and there's just battles left to fight. I think if we stopped [formal] activism right now, things would keep progressing until we had full equal rights. With assimilation comes a loss of what we had that made us special as a subculture, perhaps. Edmund White: I think that's true but I don't think it's too high of a price to pay for all the good things that will come with it. People should have the right to get married, to leave their apartment to their lover of 20 years rather than to their siblings who they haven't seen for years. People should have the right to adopt kids, to announce frankly and openly that this is my partner. The old culture had tremendous benefits but it had bigger problems. It created a lot of pain for gay people. Rex Wockner: I agree with you and yet, the experience of being an outsider often bred within one a healthy skepticism of all kinds of things that were handed down from on high as the way we were supposed to be and the way things are supposed to be and what you're supposed to do with your life. Once you realize that that which had been handed down to you about sexuality was wrong, it gave you the skepticism of: Do I want to get married and have 2.2 kids and live in the suburbs and work for a corporation and ride the subway train? A lot of [gay] people never ask those questions now. Edmund White: I agree. I think that's true. If you look at the titles of books like Virtually Normal or A Place At The Table, those are the aspirations of a lot of gay people now. I think it's partly because of what I was talking about -- this old-fashioned bohemianism died because of economic reasons; it was hard for people to go on living with a part-time job that would allow them to be artists in the rest of their time. Everybody has to have two jobs now just to pay the rent. The other thing that happened is that a lot of the more interesting people in the gay community died off and they didn't get a chance to transmit their values and their culture to a younger generation. Rex Wockner: Maybe the bohemians are still here but so many other people have come out of the closet that the bohemians are a tiny minority now. Edmund White: That's right. That could be. I can remember in the fifties going to a gay bar on the outskirts of Chicago called Louis Gage's and there you would see the one couple in that area where the woman was black and the man was white, you'd see the people who are physically challenged, you would see all kinds of odd people that didn't fit in at the bar, because the gay bar was a place for odd people. Now, even gays who are slightly odd feel uncomfortable in most gay bars, if you're too old or too fat or too something. Rex Wockner: You're handlers are loitering behind us. Thank you very much. Edmund White: Thank you. |

© 1997-2000 BEI

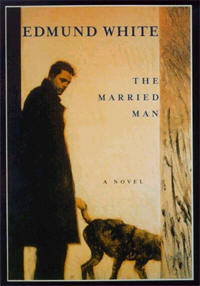

It's probably safe to say that Edmund White is America's most-

respected and widely praised gay author. His new book, The

Married Man, is getting rave reviews. The Washington Post called

it "beautifully composed."

It's probably safe to say that Edmund White is America's most-

respected and widely praised gay author. His new book, The

Married Man, is getting rave reviews. The Washington Post called

it "beautifully composed."