|

|

|

By Lilli Vincenz

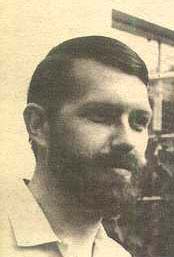

He died of squamous cell carcinoma at 1:05 a.m. on Wednesday, September 12, escaping by minutes the temporal association with the September 11 abomination. Born on November 9, 1935, in New York City, he had been a handsome man, 6'2", 175 lb., with blue-grey eyes and reddish-brown hair, who knew more than 10 languages. He earned his BA from George Washington University on a scholarship, was inducted into the Phi Beta Kappa Society, and graduated with honors in German and Spanish. He pursued graduate work in Russian and was "self-taught" in French and many other languages. The draft board contacted Otto Ulrich in 1959. Living by the code of truthfulness, he told them he was homosexual and consequently was classified as 4-F. "I had decided that as long as the government had taken the attitude that we treat homosexuals as though they had the most contagious form of leprosy, I was not going to support this government by becoming a soldier or sailor" (GAY, June 22, 1970).

Undaunted, Otto said he'd "never been arrested for anything." Then, amazingly, the department head told him about "all the homosexuals he'd known in the past who'd worked for the Library of Congress -- in fact, several of them were still working there and doing a good job." He was advised he'd be able to talk to the Librarian of Congress and "argue" his position. This never happened, and ten months later he was told that he "may stay" at the Library, which was followed by a promotion to assistant head of his department till he chose to leave in 1967. In the meantime, on July 27, 1964, the Mattachine Society of Washington's executive board approved his membership, which led to his becoming "much more militant and much more adamant that our government has to change --it's not us, because we aren't the sick ones" (GAY, June 29, 1970). On April 17, 1965, watching from across the street, he held the coats of the ten marchers at the first ever picket in front of the White House. After that he participated in demonstrations at the Pentagon and State Department, the latter act resulting "in the FBI following me around physically --because they thought I was violating the Hatch Act. I never did."

Otto Ulrich in 1965 (third from the right) at the first Pentagon protest demonstration. Author Lilli Vincenz is second from the left, and GayToday editor, Jack Nichols, is first on the right. Photo: Kay Tobin Lahusen, Courtesy of The Ladder In 1967 he was employed by Melpar, a company in private industry requiring a secret security clearance, which he had received. He had then gone to work for Litton Industries in 1968, and his security clearance was transferred. But soon he was questioned by Air Force investigators about his membership in the Mattachine Society of Washington. He refused to answer any questions on the grounds that these should have been asked before the clearance was granted. An Industrial Personnel Security Screening Board was convened by the Pentagon in 1969, where Otto Ulrich was questioned, assisted by "Dr. Franklin Edward Kameny and Miss Barbara Gittings, Counsel and Assistant Counsel." His experience resembled that of "a character out of Kafka. I feel like I've been through Das Schloss several times." Otto received five pages of "sexual interrogatories" with questions that were "simply obscene! They were pornographic!" After his refusal to answer them, his clearance was suspended. But his job remained. The ACLU took the case for restoring his clearance in 1971. Thanks to Otto's will, courage, and candor, the presumption of vulnerability to blackmail had been nullified by the public admission of his homosexuality. The D.C. U.S. District Court declared that the government may not engage in personal questions about homosexual behavior or withhold security clearances when these questions are not answered.

In 1973 the U.S. Court of Appeals for D.C. upheld the decision, and Otto's clearance was restored. He had never lied about his homosexuality, and the success of this pristine court case laid the groundwork for later restoring other rights to gay employees. Otto last worked as an indexer and translator of medical journals for the Library of Medicine. He loved music and cats. Eighty boxes of CDs and record albums were donated at his request to George Washington University's music department and the Gilham Library He is survived by one sister (who does not want her name listed), a brother-in-law, two nieces, two nephews, four great-nephews, and two great-nieces. He was fond of them.

His untimely passing saddens me because he was a beacon to me in those early years, a caring friend who'd captured my admiration." I regret that my recently renewed contact with Otto last year did not come sooner. I think about his life, which has made such a difference to the gay community, with gratitude. Lilli M. Vincenz, Ph.D., a former homophile activist, was editor of The Homosexual Citizen, published by the Mattachine Society of Washington. |

© 1997-2002 BEI

Otto Ulrich

Otto Ulrich