|

|

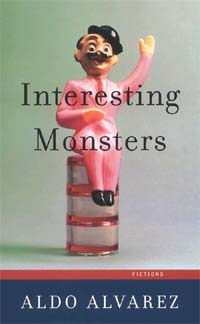

Interesting Monsters

Born and raised in Mayagüez, Puerto Rico, Aldo Alvarez earned a Ph.D. at Binghamton University and was recently a Visiting Writer at Indiana University at Bloomington. He is the founder of Blithe House Quarterly, a widely respected online journal of gay and lesbian fiction, which can be found at http://www.blithe.com. Recently, I talked with him online about his book and its origins. Jarrett Walker: One of your main characters, Mark Piper, is a techno musician who used to be a minor star. Were you thinking in musical terms as you wrote this book? Is it a piece of music on some level? Aldo Alvarez: I started to write Mark Piper stories a few years before "Behind The Music" and "Where Are They Now?" became popular. Mark Piper's a "New Wave one-hit wonder", someone who had a very brief moment in the spotlight and persists in spite of it. I think it's horrible that people would doom some performers to having extremely foreshortened careers because the market's decided they no longer have any redeemable value. Being called a has-been reduces someone to nothing. Being called a faggot pretty much strips you of value in this culture, too. I saw a metaphorical relationship between the two that wasn't predictable and didn't feel contrived. In this sense, Mark Piper is a character who wants to regain the voice, the speech that has been taken from him because he's been silenced. Literary and gay fiction have been pretty much been killed in market culture, too; every six months, an article appears that declares them dead, as if they have stopped being beautiful, moving and intellectually provocative. And no one wants to have anything to do with them. I wanted to show, through Mark and Dean, through their actions, that just because something has been declared dead it hasn't been silenced -- that it is still vital and valuable, that it is still fabulous, if only someone presented it as such and made others pay attention. In a sense, I want to do what Dean Rodriguez, Mark's other half, does as a collectibles expert at an auction house. He trades in "ephemeral" objects, like vinyl albums and toys. He showcases the value of the lot of the underestimated and abandoned. If the prose weren't melodious or jazzy, if the stories didn't work contrapuntally, like a concept album, I wouldn't be able to sustain the heightened experience of a narrative and sell it to readers. Jarrett Walker: You grew up in Puerto Rico, and although you went on to do a Ph.D. in English, your native language is actually Spanish, right? Do you still feel alienated from English as a language? Do you ever write in Spanish? Why/why not? Aldo Alvarez: I don't think I have a native speaker's perfect ease with either language as at this point I am such a cultural composite that I can't claim pure usage in one or the other.

When I was growing up in Puerto Rico, authors appeared to happen elsewhere, in other countries. There were some locally celebrated authors, but none with the kind of qualities I looked for in fiction. Writing in Spanish and having to publish in Spain or Argentina seemed even more distant a possibility than writing and publishing in English in the United States, so it wasn't a difficult choice to make. It wasn't until I read Luis Rafael Sánchez, after I finished my MFA at Columbia, that I found someone from Puerto Rico doing the kind of fiction that appeals to me. I do write in Spanish, though, when it's useful. Most of the dialogue in "Property Values" was written in Spanish, and then translated into English, so I could better represent what those voices sound like to me. Jarrett Walker: The collection is unusual in its radical mix of styles. Some stories are pretty linear, others are really surreal. Sometimes you remind me of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, other times of Jorge Luis Borges. Do you see your work as belong to a particularly Latin American tradition of surrealism in fiction? Are there other influences that are more important? Aldo Alvarez: Looking back, I've always liked authors who challenge the conventions, assumptions, etc of what's constructed to be "real" or what makes "reality" in culture -- even what constructs them as "authors", as their own genre of fiction. Writers who reassure the reader about "what we all know is true for everyone in real life" and "you can expect what you can get from me as an author" don't do it for me. This explains why I am most strongly influenced by Modernists and Postmodernists that play with and blur the distinctions between fables and lyricized reality. But certainly, they're not authors one could say are "realists". When I hit the 9th grade, I had an exceptional English teacher who introduced me to Joyce, Saki, Vonnegut and others who pretty much spoiled me forever for mainstream fiction. In Spanish, I loved Miguel de Unamuno and Ernesto Sabato. On my own, I stumbled on Kafka, which, if I recall correctly, one of my sisters read in college. She left her copy around the house.

Jarrett Walker holds a Ph.D. in humanities from Stanford University, and is a co-Editor at Blithe House Quarterly. He lives in Portland. |

In his deceptively short first book, Interesting Monsters, Aldo Alvarez covers a huge literary terrain. It could be read a story collection, or as a novel; many pieces share the same characters, but each is in a completely different literary style. Some head off in fantastical directions reminiscent of Kafka or Borges, while still coming together in the end. And while the two most recurring figures in the novel are gay men, the book takes us far beyond the confines of "gay fiction."

In his deceptively short first book, Interesting Monsters, Aldo Alvarez covers a huge literary terrain. It could be read a story collection, or as a novel; many pieces share the same characters, but each is in a completely different literary style. Some head off in fantastical directions reminiscent of Kafka or Borges, while still coming together in the end. And while the two most recurring figures in the novel are gay men, the book takes us far beyond the confines of "gay fiction."

Author Aldo Alvarez

Author Aldo Alvarez