|

|

|

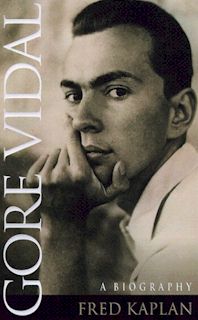

By Fred Kaplan Gore Vidal: A biography by Fred Kaplan, Doubleday, $35 cloth, 856 pages  From the perspective of the gay and lesbian movement, Gore Vidal is a somewhat ambivalent figure. On the one hand, he is undoubtedly one of the precursors of modern gay politics, and a major figure--through his writing as well as his life--in gay culture since 1948, when his novel The City and the Pillar was published.

From the perspective of the gay and lesbian movement, Gore Vidal is a somewhat ambivalent figure. On the one hand, he is undoubtedly one of the precursors of modern gay politics, and a major figure--through his writing as well as his life--in gay culture since 1948, when his novel The City and the Pillar was published.

On the other hand, Gore Vidal doesn't believe there is such a thing as "gay culture" or support a "gay movement." Although he has been as open about his orientation, for over 50 years now, as any prominent figure could be, he resists being labeled a "gay" artist. He insists "homosexual" is an adjective, describing certain acts, not a noun denominating certain people. Vidal has never, as far as I can tell, suffered--at least materially--for being a gay man, and his fortunes have not really been advanced or hindered by the rise of the gay movement, for all that he may be something of a gay icon. He and it move along on parallel tracks. Readers of Fred Kaplan's decidedly unreflective, 850-page biography will not find Vidal's ambiguities illuminated. One suspects that Vidal is having a laugh at his biographer's expense. Vidal's 1971 review of Joseph Lash's Eleanor and Franklin (reprinted, lord knows why, in Cleis Press's Gore Vidal: Sexually Speaking), could be transposed to Kaplan's production: "Unfortunately, Mr. [Kaplan] has not been able to resist the current fashion in popular biography: he puts in everything. The Wastebasket School leaves to the reader the task of arranging the mess the author has collected. Bank balances, invitations to parties, funerals, vastations in the Galerie d'Apollon--all are presented in a cool democratic way. Nothing is more important than anything else. At worst the result is scholarly narrative; at best, lively soap opera." There's plenty of soap opera in Kaplan's book. For devotees of Washington, D.C. gossip, Vidal's childhood provides almost endless fodder, starting with his mother. The spoiled daughter of blind Senator Gore from Oklahoma, she was an abusive alcoholic with a penchant for collecting husbands and a taste for one-night stands. Reading about Vidal's sex life in New York in the mid-1940s is almost like reading about gay sex in New York at the height of the post-Stonewall, pre-AIDS days of the late '70s. Vidal's haunts included the Astor Bar, the Everhard baths, cruisy Times Square, gay parties on the Upper East Side hosted by Leo Lehman, and Peggy Guggenheim's soirees in Beckman Place, where homosexuals and foreign artists mingled as equally "queer" outsiders. Everywhere there were soldiers, newly returned home or freshly demobilized, willing, even eager for a casual roll in the hay before returning to the routines of civilian life. When the recently ex-soldiers had moved on, there were ballet dancers for affection and sport. Then come travels in Italy with Tennessee Williams.

The novels and essays and plays and screenplays pour from the prolific author's pen. Better, they sell. He lives in Rome and then sets up his retirement retreat in a luxurious villa on the Italian coast, becoming, as one headline puts it, the sage of Ravello. What does it all add up to? Basically, the self-taught Vidal (he doesn't have a college degree) is a didactic author bent on spreading what he sees as a common sense realism about human sexuality, a more realistic assessment of American history, and a dry unsentimental discourse on the meaning of life: there is none. For all his erudition, Vidal is not a scholar: he has never, like his New York Review of Books comrade Garry Wills, published a book-length study of any of the topics that interest him. Seen from a perspective not Gore Vidal's, his views verge on the crackpot. For example, his basic theory of American history can be summed up in the title of fellow native Washingtonian Patrick Buchanan's recent tome, A Republic, Not an Empire. His American history novels (Burr, Lincoln, Empire, etc.) have sold well because Vidal can name drop with unabashed aplomb while peddling a conspiratorial account of American politics in which the good, simple (lowercase) republicans have been done in by a cabal of greedy politicians, bankers and businessmen bent on turning this green and pleasant land into an oppressive empire determined to achieve world domination.

Sounds good. The problem is that gay politics isn't about reversing the scoring: it's about getting into the game at all. The problem isn't that Williams didn't dedicate himself to putting gay characters and situations on stage, it is that he never put a gay character and situation on stage (at least, not without a lot of disguise and subterfuge). Vidal avoids the real issues, just as when, confronted by Larry Kramer about not speaking out on AIDS, he responds "I'm not a virologist" ("The Sadness of Gore Vidal," in Gore Vidal: Sexually Speaking). The core of Vidal's gay theory is that gay culture is all about reaction. "Although Jews would doubtless be Jews if there were no anti-Semitism," he writes in "Pink Triangle and Yellow Star," "same-sexers would think little or nothing about their preference if society ignored it." Again, sounds good. But would we, really? While Vidal's hypothetical situation isn't really subject to proof, it seems to me that the evidence of the heart as well as of history belies it. Read Plato's Symposium with a gay eye and say same-sexing doesn't play a big role in not only the story of the banquet, but in the ways the participants puzzle out the nature of love. Aristophanes takes it for granted that same-sex affection is part of the natural order and constructs a natural history of love that takes that fact into account. Surely Plato is very interested in how that affection plays out in practice. The night's interplay between Alcibiades and Socrates is not only about philosophy. Vidal's writing--not just The City and the Pillar and Myra, but his essays as well, advance an appealing theory which they belie. Without belittling his powers as a writer who has done honorable battle with the "heterosexual dictatorship" (a Christopher Isherwood phrase that Vidal likes), Vidal is not a systematic thinker. He is, in fact a brilliant gossip (Palimpsest will always be his most entertaining book) and something of a prophet, envisioning the changes that the twentieth century is working on sexual life. But, perhaps, like Moses, he is unable to leave the country of his birth and settle in the promised land of gay liberation. But then again, he is probably right in seeing in utopias only a new set of problems for humans to deal with. One thing is certain, whatever depths he may have, they remain, despite Kaplan's massive effort, unplumbed. Jim Marks is the Publisher of Lambda Book Report |

© 1997-2000 BEI

© 1997-2000 BEI

Gore Vidal (center) with President Kennedy and First Lady Jackie

Gore Vidal (center) with President Kennedy and First Lady Jackie