|

|

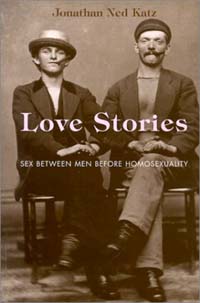

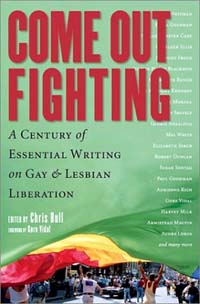

Love Stories: Sex Between Men Before Homosexuality by Jonathan Ned Katz; University of Chicago Press; 426 pages; $35.00. Come Out Fighting: A Century of Essential Writing on Gay & Lesbian Liberation edited by Chris Bull; Foreword by Gore Vidal; Thunder's Mouth Press/Nation Books; 336 pages; $17.95.  Jonathan Ned Katz begins Love Stories, his masterly study of love between

men in 19th century America, with the story of Abraham Lincoln and his friend

Joshua Fry Speed. As Speed himself recalled after Lincoln's death, "no two

men were ever more intimate" during the three years they shared a bed

(1837-1840).

Jonathan Ned Katz begins Love Stories, his masterly study of love between

men in 19th century America, with the story of Abraham Lincoln and his friend

Joshua Fry Speed. As Speed himself recalled after Lincoln's death, "no two

men were ever more intimate" during the three years they shared a bed

(1837-1840).

Yet, as Katz reminds us, what would surely raise eyebrows today hardly made a stir in Springfield, Illinois. That is because the modern concept of homosexuality did not exist in Lincoln's time. As a result, "Intense, even romantic man-to-man friendships - an institution in nineteenth-century America - were a world apart in that era's consciousness from the sensual universe of mutual masturbation and the legal universe of ' sodomy,' 'buggery,' and the 'crime against nature'." 19th century men could hold hands, kiss, dance, sleep, skinny-dip and even have sex together without bearing the stigma of sexual inversion. Today, on the other hand, teenage boys don't even shower after gym class, for fear of being thought "queer". This does not mean that sex between men was unknown in the 1800's, even if the Lincoln-Speed intimacy remained platonic. "Sodomy laws" were in effect in every state of the Union, though they were defined to cover "men's anal intercourse with men, boys, women, and girls, and humans' intercourse with beasts". In 1842 The Whip, a New York City tabloid, ran a series of articles attacking those "who follow that unhallowed practice of Sodomy," linking it to Jews and other foreign immigrants. But to The Whip "Sodomitical desire was considered a potential of all men, not a discrete minority or a separate sexual species." (More typical of its time, The Whip considered "intercourse" between white women and black men to be "a practice worse, by far, than sodomy!") It was not until the end of the 19th century that men-loving men became a separate category of humans. When in 1890 the New York Press decried the existence of a bar called the Slide ("The Wickedest Place in New York") it had no problem describing its patrons as "effeminate, degraded and addicted to vices which are inhuman and unnatural." Jonathan Ned Katz, whose first book Gay American History brought same-gender loving out of the historical closet in 1976, uncovered some new material for this his latest work of historic scholarship.

However, "During most of Whitman's lifetime, it was almost always his evocations of male-female sexuality that threatened Leaves of Grass with being banned." It was still relatively safe to write about love between men. Only towards the end of Whitman's life did the "Good Gray Poet" feel the need to downplay his poems' celebration of male love, going so far as to claim to have fathered six nonexistent children. Though Walt Whitman was not a gay liberationist in the modern sense of the word, his works have influenced generations of men-loving men. Katz's Love Stories noted Whitman's influence on his younger English contemporaries, John Addington Symonds and Edward Carpenter.

Bull, the Washington correspondent for The Advocate, is also the editor of Witness to Revolution: The Advocate Reports on Gay and Lesbian Politics. In Come Out Fighting, Bull extended his scope to create a primer of the GLBT movement from Whitman's time to our own. Bull follows a selection from Democratic Vistas with anarchist Emma Goldman's 1923 letter to German sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld and documents by Havelock Ellis, Sigmund Freud, Robert Duncan, Alfred Kinsey, James Baldwin, Donald Webster Cory... Not everyone in this book is a "gay liberationist"; as Norman Mailer and Justice Harry Blackburn share the covers with the likes of Charley Shively and Charlotte Bunch. But all of the contributors made an impact, for better or worse, on the lives of gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender Americans. It is to Bull's credit that he envisioned them all as being part of a conti nuing, and ever-evolving, movement for political change.

|

Chris Bull goes so far as to place Whitman's 1871 essay Democratic Vistas at the forefront of his

anthology Come Out Fighting: A Century of Essential Writing on Gay & Lesbian

Liberation. Here, said Bull, "the poet predicted . . . the advent of this

remarkable movement for change. He also issued a prescient warning about the

potential for religious fanaticism and the 'glacial purity' of conscience for

'devouring, remorseless, like fire and flame' the possibilities of 'manly

friendship' and 'loving comradeship,' which he equated with democracy

itself."

Chris Bull goes so far as to place Whitman's 1871 essay Democratic Vistas at the forefront of his

anthology Come Out Fighting: A Century of Essential Writing on Gay & Lesbian

Liberation. Here, said Bull, "the poet predicted . . . the advent of this

remarkable movement for change. He also issued a prescient warning about the

potential for religious fanaticism and the 'glacial purity' of conscience for

'devouring, remorseless, like fire and flame' the possibilities of 'manly

friendship' and 'loving comradeship,' which he equated with democracy

itself."

Jesse Monteagudo is a Cuban-born freelance writer who has lived in South Florida since 1964. His book reviews, news stories, essays and fictions have appeared in over thirty gay or mainstream publications and over two dozen anthologies. When not writing (or working at his day job), Monteagudo spends his time with his life partner of over 16 years or doing volunteer work for one of several South Florida organizations. He was awarded a Stonewall Award in 1994 and a Stars of the Rainbow Award in 1997 for his contributions to South Florida LGBT organizations, media and journalism. Monteagudo is also working on a book. He can be reached at jessemonteagudo@aol.com

Jesse Monteagudo is a Cuban-born freelance writer who has lived in South Florida since 1964. His book reviews, news stories, essays and fictions have appeared in over thirty gay or mainstream publications and over two dozen anthologies. When not writing (or working at his day job), Monteagudo spends his time with his life partner of over 16 years or doing volunteer work for one of several South Florida organizations. He was awarded a Stonewall Award in 1994 and a Stars of the Rainbow Award in 1997 for his contributions to South Florida LGBT organizations, media and journalism. Monteagudo is also working on a book. He can be reached at jessemonteagudo@aol.com