|

|

|

Jesse Monteagudo's Book Nook

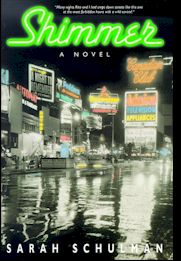

Stagestruck: Theater, AIDS, and the Marketing of Gay America by Sarah Schulman; Duke University Press; 160 pages; $14.95. Shimmer: A Novel by Sarah Schulman; Avon Books; 273 pages; $23.00.

Stagestruck: Theater, AIDS, and the Marketing of Gay America earned Sarah

Schulman her second American Library Association Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual

Book Award. After Delores, Schulman's 1988 novel, was the first, and in

between Schulman won a Kolovakos/AIDS Literature Award for People In Trouble

(1990) and a Ferro/Grumley Award for Rat Bohemia (1996).

Stagestruck: Theater, AIDS, and the Marketing of Gay America earned Sarah

Schulman her second American Library Association Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual

Book Award. After Delores, Schulman's 1988 novel, was the first, and in

between Schulman won a Kolovakos/AIDS Literature Award for People In Trouble

(1990) and a Ferro/Grumley Award for Rat Bohemia (1996).

In addition to her accomplishments in literature, Schulman also shone as an activist, a member of ACT-UP, and founder of the Lesbian Avengers, events that she chronicled in her non-fiction collection My American History (1994). Stagestruck, Schulman's second non-fiction book, came about as a result of Schulman being at the losing end of one of the current theater's most notorious rip-offs.

People In Trouble sold marginally at best (though it won the aforementioned Kolovakos Award). Rent won four Tonys, the Pulitzer Prize, and made tons of money for the producers - though not for Larson, who died of an aortic aneurysm shortly before the previews. Schulman was understandably upset. Unfortunately, her attempts to get legal satisfaction proved unsuccessful. Schulman's story about her runaround through New York's legal and publishing minefields is a cautionary tale for any would-be David who tries to topple our cultural Goliaths. Copyright law, as it turns out, did not bar unlawful use of a writer's ideas, only the "expression" of her ideas. "In fact," Schulman notes, Larson "used my ideas to express something that is the opposite of what I expressed." In People In Trouble, as in real life, most People With AIDS are colored, queer and/or poor. "Rent, in addition to its positioning of heterosexuals front and center of the crisis, and its callous privileging of straight people with AIDS over gay people with AIDS, specifically denies the actual AIDS experience, both individually and socially." Larson would argue, of course, that a show that dwells on lesbian couples, HIV+ gay men and poor people of color would not sell on the Great White Way. By "main-streaming" AIDS, Larson's Rent brought the important issues of AIDS and PWA's to the attention of otherwise apathetic audiences. Still, by "whitewashing" (in more than one sense of the word) AIDS and People With AIDS, Rent -- and the Oscar-winning film Philadelphia, which Schulman also discusses -- ignores the political issues that shaped society's response to the AIDS epidemic, mainly that it was and remains a disease that mainly strikes disempowered and unpopular minorities. Queer people, poor people and people of color are OK as long as we remain in our "proper" places. The "real world", both onstage and off, belongs to affluent, white heterosexuals, with or without AIDS. "When fake stories about AIDS that make straight people feel good are the most public narrative, reaping huge financial rewards, Oscars, Pulitzers, and whatnot, real gay people and real people with real AIDS are on an entirely different consumer pipeline, invisible to straight people, where they are subdivided into more and more precise niches while losing and being denied public services and advocates." This, of course, is a more serious issue than whether or not Larson stole from Schulman, and it is to Schulman's credit that she was able to go beyond her personal problems to discuss it. Much has been written lately about how lesbians and gay men, in the age of Ellen and Will and Grace, have "made it" into the cultural mainstream. Stagestruck reminds us just how denatured that "mainstream" is. By taking on the cultural establishment, Schulman ruined her career but reinforced her reputation as one of our leading activists. In a just world, Stagestruck should make People In Trouble a bestseller, almost a decade after Schulman wrote it. Unfortunately, Penguin Books added injury to injury by letting People In Trouble go out of print. In literature, as in life, no good deed goes unpunished. In her non-fiction, Schulman writes with the force of her convictions. She is less polemical in her fiction, which is where the strength of her literary craft comes through. This is evident in her latest novel, Shimmer. Mostly set in New York City between 1948 and 1951, it is the story of Sylvia Golubowsky, an aspiring reporter -- like Schulman a lesbian Jew and a political Lefty -- who is currently employed as a stenographer for the New York Star.

Also appearing prominently in Shimmer

are Austin Van Cleeve, a right-wing gossip columnist loosely based on Walter

Winchell, and Cal Byfield, an African-American playwright married to a

Southern white woman.

Also appearing prominently in Shimmer

are Austin Van Cleeve, a right-wing gossip columnist loosely based on Walter

Winchell, and Cal Byfield, an African-American playwright married to a

Southern white woman.

Schulman is at her best when she writes through the voice of Sylvia Golubowsky, though she disappointed me by not writing much about Manhattan's then closeted lesbian subculture. She is not as good in putting words into Austin Van Cleeve's mouth; though she tries her best, her obvious disgust for the man comes through. Still, Schulman's depiction of New York circa 1950; of the City's newspaper wars, its racial and sexual politics and the anti-Communist witch hunts of the age are well done and suggest thorough research on her part. Shimmer begins each year by listing Billboard magazine's top ten hits for the year, starting (in 1948) with Dinah Shore's Buttons and Bows and ending (in 1996) with Celine Dion's Because You Loved Me. Some things, it seems, never change. |

© 1997-99 BEI

© 1997-99 BEI