|

|

|

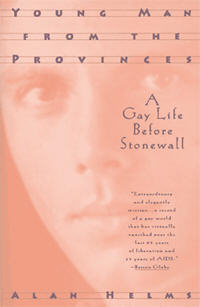

Young Man from the Provinces by Alan Helms, Avon, 1997, paperback Available through Amazon.com, $12  Beyond relating a not uncommon tale of a provincial (in this instance, midwestern America) ugly duckling ("four-eyed, brown-nosed, teacher's pet liar sissy coward" is his characterization of his childhood reputation on p. 32) who had no idea that there was anyone else like him metamorphosing into a beautiful muscular swan in a metropolis, and providing some celebrity gossip (about relationships with Noel Coward, Anthony Perkins, Luchino Visconti, among other), Helms plumbs the confusions of embodying other men's fantasies.

Beyond relating a not uncommon tale of a provincial (in this instance, midwestern America) ugly duckling ("four-eyed, brown-nosed, teacher's pet liar sissy coward" is his characterization of his childhood reputation on p. 32) who had no idea that there was anyone else like him metamorphosing into a beautiful muscular swan in a metropolis, and providing some celebrity gossip (about relationships with Noel Coward, Anthony Perkins, Luchino Visconti, among other), Helms plumbs the confusions of embodying other men's fantasies.

In the beginning of his "career" as one of the most desired young males in New York City of the late 1950s, Helms recalls that he "studied my face in the mirror to see if I couldn't find what those men saw in me. I saw how flustered they got when we met & I saw the intensity in their eyes. I saw their eagerness & desire, but I couldn't see what inspired them" (p. 71). Being slobbered over did not increase his confidence about having any worth other than sexual exchange value, however. In one of the most acute and painful passages in a book that eschews self-pity, but is far from cheerful about the spectacle of his past, the older author understands the injury-inflicting falsity of one common line: "It's such a small thing for you, & it means so much to me." I don't know how often I heard that hustle, yet it never occurred to me to say that, all things considered, dropping my pants for a blow job was in fact a small thing for them, while being pressed into the service of their fantasies was such a large, disorienting, wholly unpleasant thing for me. Though I wasn't easy to get, especially when I didn't desire the other man, anyone who persisted & wasn't downright rude could usually have his way with me if he bided his time, led me into a sense of obligation, persuaded me he cared about the "real whole me," plied me with liquor, then made his pitch. God forbid I should offend anyone, especially a "friend." (p. 102)

Eventually, he took up a position as an English professor at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. Discussion of his adjustments as an older gay man is brief. The major focus is on his earlier life as an unhappy child and then as a perplexed young object of worship and resentment. Alan Helms did survive and has provided a harrowing account of coming out in the pre-liberation era that is certain to be a classic in that genre. In that there is no shortage of coming-out stories, what I find most arresting about his memoir is its presenting the view of the objectified "hot" man. As should be obvious from my quotations from the text, the writing is highly polished (though I find the ampersands grating). His tale of a belated bildung is absorbing, and his analyses of his past eager-to-please self and the gay worlds in which he was a pleasing object are painfully acute. His memoir also contributes to the historical understanding of what semi- closeted gay society in New York of the late-1950s and early-1960s. Stephen O. Murray is the author of American Gay (University of Chicago Press, 1996), African Homosexualities (New York University Press, 1997) and ten other books |

© 1997-2000 BEI

© 1997-2000 BEI