|

Vern L. Bullough, RN, PhD

His latest contribution to the history of sexuality has been the editing of an indispensable new volume titled Before Stonewall: Activists for Gay and Lesbian Rights in Historical Context available from local gay bookstores, through such venues as Barnes and Noble or on-line from its publisher, Harrington Park Press (an imprint of Haworth Press): http://www.haworthpressinc.com/store/product.asp?sku=4646&AuthType The respect accorded to Vern Bullough by his academic peers and colleagues shines brightly in their appreciations for Before Stonewall. George Chauncey, PhD, author of Gay New York and Professor of History at the University of Chicago says of this new book that it "should become a standard reference work." Dr. Bullough is a Distinguished Professor Emeritus from SUNY. Currently, he is serving as Adjunct Professor of Nursing at the University of Southern California. For ten years, he served as Dean of Natural and Social Sciences at SUNY Buffalo, and prior to that he was a professor at California State University.

The reason her mother had left I found out was that she had moved in with a woman, Berry Berryman, who became her lifetime partner. Such scandalous conduct could not be condoned and in the subsequent breakup of the family, Bonnie was adopted by a bachelor uncle who was in the army and went to live with her grandmother. Her step brother and sister went with her step father. When I was introduced to her mother and her partner, I of course was more or less goggle-eyed and asked all kinds of questions about homosexuality. They put up with me, gave me books to read, and introduced me to their lesbian and gay friends, who like them, were not publicly identified as such. As a somewhat radical student, concerned with discrimination against racial minorities and women, I soon came to feel that homosexuals probably suffered even worse discrimination. Berry, herself, who is included in Before Stonewall, had for many years been gathering data for a study of lesbian women but she would never let me or Bonnie read it. When she died, however, the material came to us and we wrote it up. Raj Ayyar: In Before Stonewall, Dr. John P. De Cecco, editor of the Harrington Park series on gay and lesbian studies rightly insisted you should be included in this magnificent history book, taking your rightful place among those brave pioneers who were first in America to contribute to the cause of gay and lesbian rights. Dr. De Cecco himself wrote the chapter about your many contributions. You were also present in Beverly Hills at the 1998 memorial celebration of archivist/journalist Jim Kepner's life and though you're undeniably straight, you were included with pre-1969 pioneers of the GLBT movement in that occasion's historic group photo. You must have literally no compunctions when people mistakenly assume you to be gay. Is that so? Vern Bullough: Early on, as both of us began to research the topic and to occasionally write on it, we were fearful we would be labeled as gay or lesbian. Ultimately we concluded that since we had been labeled as communists for our other political activity, and somehow survived, that it didn't really matter what others called us as long as we felt we were doing and acting on what we believed.

In my interview for the deanship, my writing on sexuality came up, and I thought that this meant the job might go down the tubes. One person also asked me how my research affected my attitudes towards gays and lesbians. Much to my surprise, I got the job. I found out later that a number of the committee were gays or lesbians (only one of them publicly) and they were pleased and encouraging about my research. In recent years I have increasingly called myself a sexologist. I have written or co-written (mainly with my late wife) or edited, over 50 books, contributed chapters to another 100 or so, written roughly 150 referenced articles, and hundreds of others and made presentations or read papers in most states of the U.S. and in two dozen or so foreign countries. A couple of years after Bonnie died, I married an old friend from Cal State Northridge who had retired from the English Department. We both sold our houses and moved to a neutral site. Most of my early articles were on the history of medicine and science in the medieval-renaissance period, and my first book was on The Development of Medicine as a Profession. I have also written books on war, on poverty, on discrimination, on the development of science, a western civics text book, on women, on nursing, and on a variety of sexual topics. Shortly after my study of medicine I published a history of nursing and a history of prostitution. The prostitution book came about because of an essay, a review I'd written on the Wolfenden Report in England which urged decriminalization of both prostitution and homosexuality. A publisher requested that I follow through with a book and I was in somewhat of a quandary. Still unsure of how my colleagues would deal with homosexuality (the university had recently dismissed a young professor who had been arrested by police for soliciting), I chose prostitution. This proved in a sense to be a good first choice since after I told my colleagues it became a subject of much joking in informal meetings at lunch and elsewhere with my colleagues. I even got their help in finding the various words used to describe prostitutes. Thus, though I got labeled as a sex researcher, I did not arouse too much controversy. I regarded my most significant book on sex, Sexual Variance in Society and History, which studied non- conforming sexuality from the caveman to the twentieth century and included chapters on China, India and the Islamic world. I had two chapters on medieval Europe in which I pointed out that the changes taking place in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries were not so much in church policy towards homosexuals, but in the ability of the church to enforce laws and doctrines that it had previously ignored. Later the historian John Boswell gave a somewhat different interpretation with which I disagree. Out of the research for this book, I also published a book on attitudes toward women, entitled The Subordinate Sex which became a Penguin Paperback, and two popular paperbacks published by New American Library, one entitled Sin, Sickness, and Sanity about societal attitudes towards a variety of sexual behaviors, and the other, a short history of homosexuality (Homosexuality: A History). I was also interested in source materials for the history of sex and I was editor along with Dorr Legg, Barrett Elcano, and James Kepner, of two volumes: An Annotated Bibliography of Homosexuality, Transvestism, and Transsexualism. I also edited a Bibliography of Prostitution with Bonnie and Margaret Deacon. This was followed by an Illustrated History of Prostitution, a rewrite of the earlier book on the topic. This was later further revised by myself and Bonnie as Women and Prostitution.. The publisher Neale Watson then gathered together some of my articles on sex into a collection entitled, Sex Society and History. Bonnie and I examined new developments in sex research in the 1970's in Frontiers of Sex Research. With Jim Brundage, I edited two collections of articles (including our own) entitled Sexual Practices in the Medieval Church and a Handbook of Medieval Sexuality. Bonnie and I wrote a guide to contraceptives entitled Contraception Today: Modern Methods of Birth Control. which was revised and republished a few years later. I edited with Lilli Sentz, an update on the prostitution bibliography: Prostitution: A Guide to Sources, 1960-1992. Perhaps equal in importance to my study on sexual variance was the book Bonnie and I did on Cross Dressing, Sex, and Gender. I also did a Guide to Fertility, and in 1994, another path breaking book Science in the Bedroom: A History of Sex Research. The 90's were a prolific period for sex books including besides the two previous ones, Sexual Attitudes: Myths and Realities, How I Got Into Sex (with Bonnie and others), Gender Blending: Transgender Issues in Today's World, Prostitutes, Pimps and Whores, and Pornography 101. The last three came out of conferences sponsored by the Center for Sex Research at California state university, Northridge. I also edited with Bonnie: American Sexuality: An Encyclopedia and, by myself, a Historical Encyclopedia of Birth Control. I have not included the non-sex books. In addition I was editor of a sex series for Prometheus Books which published a number of books but also three classics translated from the German by Michael Lombardi-Nash and for which I wrote the introduction: the two volume collection of Ulrichs, and the books on homosexuality and transvestism by Magnus Hirschfeld. I could go on but this seems enough.

I first became active in working for civil rights of African Americans and Mexican Americans. While I continued to do so, for a time especially in the Black civil rights movements, there was a reluctance to accept Caucasians in any conspicuous way, and while I continued to be active, I devoted more energies to women's rights movements, and then when there came a period of some hostility to males, I was more visibly active in the gay and transgender movement. For a while within the gay community there also was a reluctance to deal with "those outside of the community" and I became less noticeable here also. While I continued to research, my move to Buffalo removed me from some of the more vicious infighting in gay circles. I did keep in contact with many of the leaders, and was an active supporter of the gay and lesbian community in Buffalo. I also continued to speak on the topic and appear as expert witness including three federal trials, one of which was totally concerned with gay and lesbian pornography. By the time I returned to Los Angeles, I was welcomed back by all factions and managed to remain friends with all of the groups. I was looked upon as a pioneer and accepted without difficulty. The most reluctant of the groups to become politically active was the transvestites, and they were more or less pushed and shoved by the transsexuals. At the same time, the gays and lesbians in the 70's began to realize the importance of pulling together and have done so. In a sense the unions of gay, lesbians and transgendered is a marriage of convenience, and it works better in some communities than others. There are still a lot of alienated and powerless people in all of the minority sexual communities and the problem is to get them involved. Raj Ayyar: Some of the early American gay and lesbian pioneers didn't see eye to eye with each other and could sometimes become engaged in some rather public disputes. You, on the other hand, are renowned for having managed through the years to stay in touch with nearly all of them. What were some of their more important squabbles about and how did you manage to keep above the fray?

I participated in the first gay parade organized by Don and others which was a car caravan traveling through Hollywood with horns blaring. My wife and I were put in the front seat of the convertible leading the parade. Included in the parade was Harry Hay who somehow got lost and went off on his own. After the ACLU adopted the policy on the rights of gays, I spoke to a large number of service clubs in greater L.A. as well as churches and ACLU chapters on gay rights. I became vice president of the Institute for the Study of Human Resources, the foundation Reed Erickson had set up for ONE, Inc. Since Reed rarely showed up at meetings, I ran the meetings. I did book reviews for Tangents and also for ONE. I also became involved with SIR in San Francisco as a Los Angeles contact, and with the split-away Kepner group in Los Angeles. I think the fact that I was not identified by the gay community as being gay helped me straddle the various divisions. I could be a spokesman for them when they needed one and I genuinely liked most of those I knew. I think there were often suspicions about me but eventually they accepted me for what I was: a researcher interested in them as people and willing to fight for them. For a time I even ran a gay hot line out of my house. I guess the major squabble in Los Angeles which to some extent still continues was between Dorr Legg and Don Slater. It was in part a matter of personality and in part a struggle to determine which direction the movement was going. Both Dorr and Don, in a sense were integrationists, wanting a broad movement of all types. Don felt that magazines and media were more important than Dorr. Dorr wanted to educate the gay community and the community at large. In part also the struggle was over money. The transsexual Reed Erickson began supporting ONE in the early 1960's and the question was how the money would be spent. Since Dorr was the contact with Eric, he had the major say and put the scarce resources into his projects, cutting out Don. The split caught me in the middle and it was in the middle where I remained. For a time Kepner split with Dorr and went off on his own but I insisted when we did the bibliography that Jim be included since he had such a valuable library. Dorr and Kepner worked together on the bibliography with me, but Dorr wanted to prevent Jim from being listed as one of the editors. Sometimes things got petty. Jim Kepner also tried to keep a middle position. Later other leaders emerged in the Los Angeles community including Morris Kight, and the struggles were as much over power and publicity as over issues. Probably the most intransigent was Dorr and he fought to maintain the ONE he wanted. His access to Eric enabled him to do so. He was also, however, intransigent with Eric. After Erickson had bought ONE the property for their new headquarters, Eric wanted it to include a center for Transsexuals and Transvestites. Dorr refused and the result was a court fight which more or less left ONE bankrupt but with a house and headquarters and it further split the movement. It was not until a new generation came in, more or less free of the battles, that the animosities died down. Raj Ayyar: What might you recall as some of your most memorable meetings with the gay and lesbian movement's earliest pioneers?

As you perhaps know, I received a grant from the Erickson Foundation to write my Sexual Variance book which is dedicated to him. How I got the grant is a long story. I was in Egypt when Evelyn Hooker wrote me asking me to write a brief history for her report on homosexuality which was to come out in 1968. I felt I could not meet her deadline and turned her down. At about the same time the NIMH task force on homosexuality which she chaired invited me to submit a grant proposal for a history of homosexuality. I also told them I could not do so for a year in order to meet other commitments. They told me to submit then. I did, but by the time I did, they had lost all their money, and regretfully turned me down. The withdrawal of federal funding meant that government publication of the Hooker report was also dropped. It was eventually published by ONE. After my grant proposal had been turned down by the NIMH, Reed Erickson came forward and gave me a four year grant, a much more modest one than I would have gotten from the NIMH, but enough to get some help to finish my Sexual Variance book.

Vern Bullough: I would never have predicted that the gay and lesbian movement would so rapidly achieve what they have today. In part, I think it happened because it took incremental steps rather than attempting a revolution. The effect was revolutionary but it is only looking back that it seems so. I remember early on debating the issue of gay marriage with Don and Billy Glover. I thought it was unimportant and I still think it is in terms of legal standing since domestic partnerships (which I have with my second wife) furnish the necessary legal protection and who knows or cares. But then I have second thoughts when I realize the symbolism of gay marriage is all-important, and it was this that converted me. Winning the right to marriage would force some of the most reluctant members of society to come to terms with gays and lesbians. On another issue, children of gays, I have often appeared in court as an expert witness in support of gay parents or in support of gays involved in custody decisions. I must admit in the first two cases, I was not very successful, but gradually I became very successful. I don't think it was so much me as the changing attitudes of the judges and others. I think that even if the sodomy laws are not declared unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court, the future will still bring this about. I think the key to success has been organization and organization became stronger when more people were willing to stand up and be counted for gay rights. In the early movement I was a public spokesman because few gays and lesbians would come out openly. Now there is no need for people like me to be a spokesperson and it would be insulting to the gay community if I attempted to do so. Raj Ayyar: You've been a lifelong board member of the American Civil Liberties Union. In fact, you were responsible for having been first in the USA to persuade an ACLU chapter to defend gay and lesbian civil rights. Could you say a few words about this extraordinary accomplishment? And, of course, about the free speech and freedom of assembly values you feel so strongly about and for which the ACLU stands? Vern Bullough: I mentioned the ACLU briefly. I have been on the state boards in Illinois, Ohio, Southern California, and western New York. The problem in getting a policy was that most of the affiliates looked to the national for policy and the national board was opposed. I remember talking to the national director of the ACLU about gay rights when he was visiting in Ohio in the middle 1950's. He indicated that he was violently opposed and saw this as a perversion of civil liberties and any chapter leader such as myself who tried to somehow include gay rights in our agenda would be in trouble with the national. He was very homophobic, almost apoplectic about it. When I moved to southern California, then the largest affiliate in the nation, it was also the oldest. It had been established in the 1920's and was accustomed to setting policies and taking actions which did not necessarily agree with the national. I agreed to come on the board if I could work for gay rights, and the then executive director, Eason Monroe, seized on my willingness to do so. We called together a committee including Dorr and Don and some ACLU board members and quickly drew up a policy. Before finalizing it, however, I presented it to the board and told them what we were doing and that it would be a major breakthrough both for the ACLU and the gay community. There was some opposition but I tried to answer the questions. I went on speaking engagements to the local chapter and the next time the policy was brought up it was passed without a dissenting vote although there were some abstentions. We immediately went into action and began considering cases. In the meantime, I established a hot line to deal with legal problems of gays who somehow were unwilling to contact the local office. I got a lot of people who said they were innocent of soliciting, some of which I persuaded the ACLU to accept. The problem was that many were not willing to go public with their cases and this took encouragement from me and others to do so. Fortunately a gay man from Orange County came on the ACLU Board who was openly and avowed in his homosexuality, and he took over much of this work. A couple of the members of the board itself who previously had remained silent also came out of the closet and became active. The ultimate result was the establishment of a separate legal defense team in the ACLU office of Southern California to bring cases and supported by the national ACLU. We also soon established a transgender complaints center as well. In a sense it was like the gay movement itself, the first tentative efforts gave courage to others who gave courage to still more and the snowball grew. In these days when Lambda and other groups are active, the ACLU is perhaps not so important, but back then it stood alone. I was active in other causes in ACLU including rights to medical treatment, abortion rights, sexual harassment, drugs, et al. New issues keep coming up which still demand attention and it remains the one indispensable organization in my mind. Raj Ayyar: Could you name three of your accomplishments during a long and satisfying life about which you feel most proud? Vern Bullough: I guess the most significant event in my life was my marriage to Bonnie. We married when I was 19 and she was 20, and I was disowned by my mother for it. She eventually came around but it was the ability for each of us to turn to the other for support which got us through some of our crises. I am particularly proud of my children. Bonnie and I had two of our own biological children, one of whom was killed (murdered is a better term) as a young teenager, and three of whom are adopted: one of Korean background, and two of mixed race or black. My one daughter is a lesbian and my youngest son is gay. As one of the initial sponsors of Parents and Friends of Gays I had always admired those parents who became active, and then when many years later my two children came out, I realized how even with sympathetic parents such as we were, just how difficult being a gay child might be. As I age, I guess one of the great joys is now getting recognition by many of the groups I worked for. It makes me feel that my life was worthwhile. Receiving an award for my distinguished contributions to the field of sexuality by the Society for the Scientific Study of Sex was very important. Raj Ayyar: What are some of the most significant ingredients in your latest book, Before Stonewall? Vern Bullough: The only way the book could be accomplished was by cooperation of the contributors and subjects. Wayne Dynes who had originated the idea turned over four biographies to me (including one I had written) and urged me to go ahead because he said he could not get cooperation in the gay community because he said it was too factionalized. I avoided some of this by not trying to censor what anyone said. I must also admit that I found all of my contacts to be uniformly helpful, and gays and lesbians of all walks of life helped me. Surprisingly it turned out that I knew most of them through some contact or other. The problem was limiting the size of the book and some of my choices were rather idiosyncratic. Still, I think they do convey just how different gays and lesbians are from each other and how it takes all kinds of people to make a movement.

Vern Bullough: I think the person most responsible for the change in attitudes was Alfred Kinsey. The Kinsey reports challenged Americans to face up to the reality of sexuality. Some of the other researchers were also important, including Martin Weinberg, Colin Williams, Paul Gebard, Wardell Pomeroy, Marilyn Fithian. and William Hartman. While William Masters and Virginia Johnson should belong because of their overall contributions to sex, they were not very good on homosexuality. Neither, for that matter, was Albert Ellis but he later changed his mind. Politically, Ted McIlvena in San Francisco was important since he established a bridge with religious groups through his work with the Glide Foundation and later through the establishment of his Institute. In retrospect, I believe he should have been included in Before Stonewall. Raj Ayyar: Are homosexuality and heterosexuality part of a naturally integrated continuum in human behavior? Or do you see both same-sex and opposite sex attractions as two totally distinct entities?

Raj Ayyar: Are there different standards of gayness and coming-out appropriate to each culture or is there a universal yardstick? Vern Bullough: I do not think there is a universal yardstick. I do think that as far as there is a biological factor, there are some similarities across cultures. A significant number of gays seem to do better at some occupations than do their heterosexual rivals. I think this is true in all the cultures I have examined. On the other hand, the gay need or willingness to conform to heterosexual norms, has made it difficult to note any; "gay" or "lesbian" characteristics in large numbers of people. I am still occasionally surprised when an acquaintance tells me in confidence she or he is homosexual. It might well be, however, that I am not that observant since it has never mattered to me who was or was not homosexual or heterosexual. Raj Ayyar: What are some new paths in multicultural gay studies? Has enough been done to research different ethnic and national gay histories? Vern Bullough: One of the difficulties I have with gay studies is that potentially it is restrictive and narrowing. I would much prefer studies of sexuality which can examine all the varieties of sexual expression. There are, for example, both heterosexual and homosexual sado-masochists. What, if there is one, is the difference? It is still important, however, to hunt down and identify gays and lesbians in the past in order to emphasize just how such individuals have contributed to society and civilization. In this sense gay studies and lesbian studies are important just as women's studies is. They give a different perspective to our tradition and force us to look at the tremendous variety in people. Hopefully as the barriers to being homosexual decrease, we can incorporate this information into the overall picture of society we have and find differences and similarities between us all. Raj Ayyar: What basic attitudinal changes regarding human sexuality would you most like to see taking place in humanity's developing consciousness? Vern Bullough: The problem with human sexuality is that it is still a more or less forbidden subject. While the U.S. government gives grants for sex education, most of the students learn little about sex. They have some anatomy and learn how babies come about but they do not look at the clitoris in women or talk about the importance of sexual satisfaction. They mention homosexuality in passing but in a negative way. In the past, when farm animals were around, everyone knew something about sex. I took my mare to a stallion when she was in estrus. How many growing children today have any idea about what importance sex is to the world and how we need to not only emphasize the evils and dangers but the joys and pleasures Raj Ayyar: I, for one, am grateful, Dr. Bullough, for all you've done on behalf of gays and lesbians throughout the world. You've remained among our most capable defenders and thus mere gratitude seems nearly too weak a term with which to thank you. If you have any closing comments, we'd welcome whatever it is that you'd like to say. Vern Bullough: I worried as I read your brief introduction that you made me sound as if I walked on water. I don't. It does make me proud, however, that I played some role in societal changes of attitudes toward homosexuality. |

Vern L. Bullough, RN, PhD is the editor of the highly acclaimed Before Stonewall

Vern L. Bullough, RN, PhD is the editor of the highly acclaimed Before Stonewall  Before Stonewall relates the history of several of the gay movement's pioneers

Before Stonewall relates the history of several of the gay movement's pioneers  Interviewer Raj Ayyar

Interviewer Raj Ayyar  Dr. Virginia Prince was the publisher and editor

of Transvestia, America's first transvestite

publication

Dr. Virginia Prince was the publisher and editor

of Transvestia, America's first transvestite

publication  Activist Jim Kepner

Activist Jim Kepner  Del Martin (left) and Phyllis Lyon (right), founders of The Daughters of Bilitis, America's first lesbian organization,

with GayToday's Jack Nichols

Del Martin (left) and Phyllis Lyon (right), founders of The Daughters of Bilitis, America's first lesbian organization,

with GayToday's Jack Nichols  Dr. Evelyn Hooker

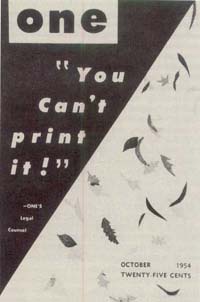

Dr. Evelyn Hooker  Radical gay 1960s publication One

Radical gay 1960s publication One  Don Slater: Taught Bullough homosexuality was just an aspect of one's being

Don Slater: Taught Bullough homosexuality was just an aspect of one's being