|

|

|

|

David Carter: Historian of The Stonewall Riots |

|

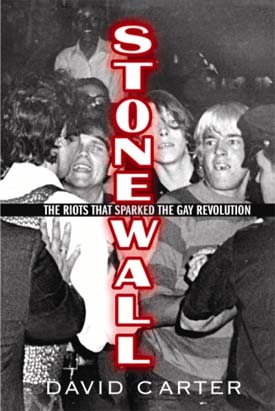

David Carter is a fellow gay historian, as well as a good friend. St. Martin's Press has just released his great new book Stonewall: The Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution, and after reading it, I wanted to ask him some questions about the process. His perceptive, thoughtful answers appear below:

Paul D. Cain: Where's Sylvia Rivera? Duberman's Stonewall placed her at the bar on the first night of the riots, yet your book makes absolutely no mention of her (although you do mention her buddy, Marsha P. Johnson). Do you think that, like so many others, she fabricated her remarks about being there? David Carter: Yes, I am afraid that I could only conclude that Sylvia's account of her being there on the first night was a fabrication. Randy Wicker told me that Marsha P. Johnson, his roommate, told him that Sylvia was not at the Stonewall Inn at the outbreak of the riots as she had fallen asleep in Bryant Park after taking heroin. (Marsha had gone up to Bryant Park, found her asleep, and woke her up to tell her about the riots.) Playwright and early gay activist Doric Wilson also independently told me that Marsha Johnson had told him that Sylvia was not at the Stonewall Riots. Sylvia also showed a real inconsistency in her accounts of the Stonewall Riots. In one account she claimed that the night the riots broke out was the first time that she had ever been at the Stonewall Inn; in another account she said that she had been there many times. In one account she said that she was there in drag; in another account she says that she was not in drag. She told Martin Duberman that she went to the Stonewall Inn the night the riots began to celebrate Marsha Johnson's birthday, but Marsha was born in August, not June. I also did not find one credible witness who saw her there on the first night. Paul D. Cain: How important a role do you think Craig Rodwell played in our remembrance of the Stonewall Riots today? I've heard it said that without Craig, it would have been just another bar riot. Craig certainly politicized the event by shouting "Gay Power" during it, and then by moving the Annual Reminder from Philadelphia on the 4th of July to New York as Christopher Street Liberation Day.

Paul D. Cain: Thank you for adding the section about Alfredo Diego Vinales, as I've always found his ordeal particularly horrifying. Vinales, a 23-year-old Argentinean national with an expired visa, jumped from an upper floor of the New York City's Sixth Precinct police headquarters following a raid on a gay bar called the Snake Pit in March 1970, impaling himself on six ice pick-sharp iron spikes. Fortunately, he survived. Do you know whatever happened to Vinales afterwards? I thought I read somewhere that he returned to Argentina. David Carter: No, and I wish I did. I think I also heard or read that he returned to Argentina. It'd be a real coup for a historian to find him and interview him, assuming that he's still alive. I knew for a while a waiter at a restaurant I go to who is from Argentina, and he made some inquiries on my behalf but was never able to track him down. I also ran into a woman at an event who told me that he was the son of an ambassador, something I had never heard before, and I don't know if that is true or not. I worked hard to make the Diego account as complete as I could, and I think it may now be the fullest telling of the Snake Pit raid and its aftermath. Paul D. Cain: With whom else do you wish you could have spoken in conducting your research? Whose absence makes the book less insightful than it would have been with his/her presence? What material sources were you unable to find that you wish you could have? David Carter: Well, while I used a number of interviews with Craig Rodwell (and I did know him slightly), I really wish I could have done extensive interviews with him. You see, when I interviewed someone, I interviewed him/her at great length. For example, I have 15 tapes of Tommy Lanigan-Schmidt and almost all my tapes were 90-minute tapes. A number of the people I interviewed told me that they had been interviewed many times but that no one had ever interviewed them properly before, i.e., in depth. And so I wish very much that I could have interviewed Craig: if he had had the patience, I imagine I'd have done around 20-25 tapes with him. But the one I wish I had the most that I did not have was Marty Robinson, for I feel that he is one of the most important figures in all of gay history. I say that because, again, Stonewall would mean nothing if it had not led directly to the gay liberation movement, for it was that movement that broke the dam and set us free, and in my view it was GAA more than any other organization that made the gay liberation movement spread, and Marty Robinson was the primary genius behind that organization. I'm told that at the end of his life Marty felt embittered over how history had largely ignored him and therefore did not preserve his own papers, so that few of them have survived. Similarly, I wish very much I could have interviewed Jim Owles, who was so important in GAA. I also very much wish I'd been able to interview other prime movers in starting GLF: Bill Katzenberg, Michael Brown, Charles Pitts, Bill Weaver, and Lois Hart.

Paul D. Cain: Was the structure of Stonewall your idea entirely, or did your editors guide you? As a historian, I found the first section of your book ("Setting the Stage") immensely helpful to understanding the riots in context, and the second section ("The Stonewall Riots") will probably be the best historical record of what happened at Stonewall that we will ever have. David Carter: The structure of the book was my own idea, for it seemed to me a story with a pretty clear beginning, middle and end, although I did put the beginning in mainly to provide context. Also, two friends of mine, a heterosexual couple, suggested that I start the book with the material on Greenwich Village, for they found it very compelling and felt it would therefore be a good way to draw the reader into the story. One of my main models for the book was Sebastian Junger's The Perfect Storm. In that book Junger went back and forth from small essay-like sections that were very objectively reported on such subjects as marine ecology or the physics of boats to the real-world stories of men fishing and living on boats. I also tried to go back and forth between presenting more objective legal and political information and real-life examples of the effects of laws and policies. But I should add that Michael Denneny and Keith Kahla are both very good editors and made a number of suggestions that did much to improve the book. Paul D. Cain: It must have been a great help for you to live in Greenwich Village while writing Stonewall. What insights do you think you gained by living there that helped you understand what a non-local writer wouldn't have? David Carter: I agree. I think the chief insights I got by living here were about the role of the physical geography. I only noticed it after I lived here at length. I suppose a visitor could have picked up on that, but I think it unlikely. I also think I absorbed a lot of information by osmosis almost, some of which I'm probably still not even conscious of, it's just part of me. And sometimes one has to look at something a thousand times before one sees before the truly telling detail. Paul D. Cain: You conducted an extraordinary amount of research, and you discovered some quite obscure sources along the way. How ever did you find all of this material? Was this, again, another advantage of being in New York City, and having its public library system at your disposal? How, then, did you organize and whittle down all of this research into a book? What did you have to omit that you wish you could have included? David Carter: I became so consumed with wanting to unravel the mysteries about this event that I was determined to leave no stone unturned. It was as if I was possessed by a drive to learn the truth, and so I pursued every lead I could as far as I could. A lot of it was simple: I opened every gay history book I saw and looked at the index under Stonewall. I talked to every person that I thought might know anything. When I interviewed someone I asked them every single thing I could think to ask them and tape-recorded it all. Once I was walking by the former Stonewall Inn and I saw a young man, college-age, walk out of the doorway going up to the second floor when it was still an apartment. I thought, well, maybe he's heard something about the history of the place. He said that a professor at Columbia University had told him that a prostitution ring used to be run out of the second floor: a rare corroboration of that very important fact. At the same time, I tried to be as objective as I could and as careful as I could in collecting all the information, while not telling anyone my conclusions for ten years so as not to take a chance on someone hearing it repeated and feeding it back to me as proof that that person was a reliable witness. So it was a very lonely process, not having anyone to talk to about my conclusions.

At the June, 2004 Convention of the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists' Association in New York City, David Carter's Stonewall was discussed on a panel celebrating the 35th anniversary of the riots.

Left to right: (1) Dick Leitsch, former Executive Director, President and Vice-President (1964-1972) of the New York Mattachine Society (2) Jack Nichols, pre-Stonewall activist and author, Editor of GayToday.com (3) Charles Kaiser, panel moderator and author of The Gay Metropolis and (4) David Carter, author of Stonewall: The Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution

At the June, 2004 Convention of the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists' Association in New York City, David Carter's Stonewall was discussed on a panel celebrating the 35th anniversary of the riots.

Left to right: (1) Dick Leitsch, former Executive Director, President and Vice-President (1964-1972) of the New York Mattachine Society (2) Jack Nichols, pre-Stonewall activist and author, Editor of GayToday.com (3) Charles Kaiser, panel moderator and author of The Gay Metropolis and (4) David Carter, author of Stonewall: The Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution Photo By: Randolfe H. Wicker Whittling the material down was partly a matter of a process of selection. In other words, after a certain amount of research, it becomes clear that some documents are more important than other documents and some persons are more valuable sources than others. And if I had many tapes of interviews with key persons I interviewed, it became clear that portions of those tapes are more important than others, and so, since I didn't have enough money to pay to get all of the tapes transcribed, I told the transcriptionists to transcribe certain tapes or portions of tapes. For some key chapters, I proceeded by collating material. For example, I collated everything I had collected on the Stonewall Inn into one document and organized it both by subject matter (e.g., "who went there" "who owned the Stonewall Inn") and by physical layout ("the lobby" "the coat check" "the front room"), and that began to give me a lot of clarity--I could see what was corroborated by multiple sources. It finally suggested a structure to the chapter on the Stonewall Inn, for I thought it made sense to take the reader through each part of the Stonewall Inn, as if on a tour. Eventually I added other material, but that part of the structure remained until the final draft. Likewise, I felt the most important material for a detailed recounting of the riots was the material written in 1969 [when the Stonewall Riots occurred - pdc]. I determined both that there was a lot more material written in 1969 than anyone realized, that it contained much more material than it was given credit for having, and that it was much more accurate than was widely believed. I also discovered some accounts published in 1969 that were previously unknown. So one of the first things I did was to enter those texts into a computer and then I collated them all into one long document according to subject matter: how much liquor was seized? What time did the raid begin? How many people were arrested? I found that there was an amazing degree of agreement among these accounts, and that by combining what was in the various accounts, one could build up a very detailed description of what had actually happened. After I had the basic outline from what was written in 1969, I then added on to that the most illuminating and compelling material from credible accounts written after 1969 and from interviews, whether that was from interviews I had conducted or from interviews other historians had conducted. Sometimes when I could not figure material out, I had to study various accounts over and over to try to determine what had happened. Sometimes I drew columns on several sheets of paper and entered the parallel accounts to note the differences and similarities, even color coding it, and then laid the sheets of paper side by side to study them. If I felt I did not really know where something fit, I put the material where it made the most sense dramatically or contextually and informed the reader that there were several possible interpretations as to the timing or meaning of an event. I always think of writing about the riots themselves as being like building a ship inside a bottle: difficult, tedious, painstaking, but very satisfying and ultimately very exciting. Yes, I discarded so much material: the original draft was twice the length of the finished book, and I kept on making important new discoveries, which meant adding more material, which meant cutting more from chapters that had already been cut and cut again. Finally, though, it is a much stronger and better-written book from being so much shorter. One thing that gave me the courage and clarity to cut was a maxim my editor Keith Kahla originated: the writer confuses what he needs to know to write the book with what the reader needs to know to read the book. The original chapter of the book was discarded. It was about how a young gay man who'd been shot at on the streets of downtown Atlanta heard of the Stonewall Inn in Atlanta, Georgia and moved to New York in part to go to the Stonewall. Material on lesbians was discarded (because it was not directly relevant to the story), the final chapter, an epilogue, was discarded, as well as a fun chapter titled "Reverberations" on how word of the riots quickly spread across the nation and the world. It wasn't fun cutting the material, but having deadlines and a limited number of pages the publisher would accept helped!

David Carter: I did not begin with any assumptions for I had no basis to make any. I was not part of the pre-Stonewall era and had not lived here before 1985, and so I felt objective. My attitude was to let the cards fall where they may. I did not set out with any theories that I wanted to prove or disprove, nor was I intending to make anyone a hero or a villain. The three founders of GAA were heroes of mine, but my focus was on writing a history of the Stonewall Riots, and their being heroes of mine was based on what they did after the riots. The assumption I did set out with was that there were enough sources that had either been unused or not fully used that it would be possible to write a full account of the Stonewall Riots. I did discover some extremely surprising things along the way, but I did not set out with any assumptions. One exception, however, was that I felt somewhat doubtful about the extent to which homeless youths and other marginal persons had been involved, but it was not a deeply held feeling, and as anyone can see-I ended up dedicating the book to the homeless gay youth and put them on the book's cover-I certainly was very open-minded in my research on that subject. Paul D. Cain: You spent ten years assembling this work. Were there times you just wanted to throw up your hands and abandon it? What were your high and low points along the way? David Carter: Although there were very frustrating moments along the way, I don't think I ever thought of abandoning the project. The whole thing would have been much more easy as well as a more pleasant experience if I had not had to worry about the frauds, people who have based their résumé on their alleged participation in the Stonewall Riots. I guess that finally the hardest part was writing the book and then it was very hard to cut it down, leaving out a lot of material that was compelling but didn't contribute to the narrative flow. An actor friend of mine consoled me by saying it was the nature of creative work: we have to murder our own children, and that's more or less what it felt like. Luckily, I feel happy with the surviving offspring! I also had a tremendous conflict, for I had written a long history of the homophile movement in New York before the Stonewall Riots, and my first editor, Michael Denneny, felt it should almost all be cut, for it did not lead to the riots: the riots were a break from the Mattachine/homophile approach and most of the rioters probably were not even aware of the existence of the Mattachine Society. Yet somehow I felt that it was relevant, but it seemed counterintuitive: how could I answer Denneny's objections? Finally, I was discussing this with a very intelligent friend of mine and he said, well, revolutions always happen after periods of liberalization. He said it was De Tocqueville who had made that observation. And I saw how this would make sense: one's expectations are raised but not met, so one rebels. And this resolved that crisis for me. I also then found a quotation by Craig Rodwell that I had forgotten, where Rodwell-who had quit the homophile movement because he felt it was not militant enough-credited the Mattachine Society with making Stonewall possible. So then I felt that my intuition was validated, that the Mattachine Society's ending the most egregious practices of the New York Police Department had given hope to New York's homosexuals, laying the groundwork for the revolution. I also later read about the French and Russian revolutions and saw that they --as well as the American Revolution, whose history I already knew-- had come after periods of liberalization. Paul D. Cain: Thank you for pointing out to me the importance of physical geography upon history. I'd never made that connection until I read Stonewall, and it does explain a lot about why the Riots had the impact they did. Do you think that nexus might be an eye-opener for others as well? David Carter: Yes. Many commentators had observed that the irregular layout of the Village's streets was in the rioters' favor, but no one had ever made any observations about the role of the local geography beyond that one fact. In fact, Lucian Truscott, one of the two Village Voice reporters who covered the riots, saw some of the implications at the time. He was on furlough from the Army and a few months later, back in the service, heard a lecture on riot control. He volunteered his observations from the Stonewall Riots, getting up to the chalkboard and diagramming how the streets had worked against the police. His talk was such a hit that he was asked to repeat it over and over to other classes. So the Stonewall Riots were actually used to teach the U.S. military about riot control. Paul D. Cain: Since, as you point out, there were other gay rebellions before Stonewall like the California Hall and Compton's incidents in San Francisco that Stonewall mentions, as well as a notable bar riot in Los Angeles around 1967 that you don't mention, I've always thought that the Stonewall Riots were arguably somewhat self-referential: Since New York is the media capital of the world, New Yorkers think nothing important happens unless and until it happens in New York City. Then and only then, when it plays in the media with a New York slant, does it become important to the rest of the world. Setting any possible New York bias you may have aside, do you think there's any truth to that? David Carter: Not really. I feel that I address this issue in the book's Conclusions, how the fact that the Stonewall Riots happened had a lot to do with specific factors unique to New York. These cannot be laid to hubris because they are factually true: e.g., the layout of the streets combined with the vast homosexual population, the severe repression of that population, the fact that NYC is a media capital. Of course some of the contributing factors were true everywhere in America. Everyone had witnessed the black civil rights movement, for example, but many of the factors were also unique to New York City (there can only be one largest gay population center and there can only be one largest gay bar in the country, and they both were in New York City, not surprising since it's the country's largest city and it had America's most famous bohemian district, so a lot of this is simply logical). And don't forget that people such as Dick Leitsch, Craig Rodwell, and Arthur Evans came here to be in New York City because it was a refuge at the time (or in Dick's case, a cultural mecca, but all the same, once here he met Craig and got involved in one of the largest and most active Mattachine chapters in the U.S.). Yes, New York is a media capital, but that has a political effect that is real. You see, it's the combination of all these factors that made the riots possible, and New York's size and specific history produced not only those factors but produced them in combination with each other.

Paul D. Cain: How was your event on June 2 at the New York Historical Society? Good turnout? Good questions? Good response? Good sales? Will you be touring to promote the book? If so, where and when? David Carter: The launch sold out and the audience seemed to enjoy hearing from all of us, but particularly the panelists who were at the Stonewall Riots, and especially [former Deputy Inspector] Seymour Pine, who gave a lot of new testimony publicly for the first time. The response was tremendous and I signed many books. A lot of young people bought the book and so many of them thanked me for writing the history, so that was nice. I will be going to Washington, D.C. on June 26 for a reading at Lambda Rising, and, as you know, something is possibly in the works for San Francisco for July or August. |

David Carter, author of Stonewall: The Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution

David Carter, author of Stonewall: The Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution  David Carter: I think it's unfortunate that every member of our community does not know Craig's name, as well as the names of many others such as Marty Robinson, Arthur Evans, and Jim Owles, to mention just a few of the most important ones. Here I'm naming people whose role has been at least partly acknowledged for years in published histories and documentaries, so there is no excuse at this point in time for their not being better known. But to focus on Craig, while he may not have been the most important person there in terms of causing the riots to break out, he was certainly the Stonewall Riots' primary propagandist-and I use that word in its most positive meaning. As Michael Denneny said to me, Craig had a kind of cultural genius, so that his idea to celebrate the Stonewall Riots annually nailed it to the hide of history.

David Carter: I think it's unfortunate that every member of our community does not know Craig's name, as well as the names of many others such as Marty Robinson, Arthur Evans, and Jim Owles, to mention just a few of the most important ones. Here I'm naming people whose role has been at least partly acknowledged for years in published histories and documentaries, so there is no excuse at this point in time for their not being better known. But to focus on Craig, while he may not have been the most important person there in terms of causing the riots to break out, he was certainly the Stonewall Riots' primary propagandist-and I use that word in its most positive meaning. As Michael Denneny said to me, Craig had a kind of cultural genius, so that his idea to celebrate the Stonewall Riots annually nailed it to the hide of history.

Marty Robinson

Marty Robinson  Gay activists march for equal rights in the Stonewall era

Gay activists march for equal rights in the Stonewall era  Interviewer Paul D. Cain

Interviewer Paul D. Cain