|

Trebor Healey: Well, I don't know if it's my courage. I just got pushed into it. Sink or swim. I've always been honest to a fault. Maybe even obsessively honest. But I think life is a school and you have to inquire to learn. I'm not here to accumulate wealth and be comfortable. I'm curious about how strange life is. Demons are interesting, and they're teachers. That seems obvious to me. What scares you has a lot to teach you. The only way past is through, Jungian integration of the shadow, all that. That's how you grow. Raj Ayyar: I liked the fact that Through It Came Bright Colors is a gritty novel that avoids two gay novel traps: the old 'homosexual sad ending' cliche (what I call the Death in Venice syndrome) and the fairy tale happy ending. Are there bits and pieces of you, shards of autobiography in the novel? Trebor Healey: Yes. I have a brother who went through a very difficult cancer experience, and I had a lover who was a lot like the character Vince in the novel. I don't believe in happy endings or sad endings. That's not how things go. I think it's a limited and somewhat dishonest view. Everything begins and ends with possibility. Everything is always in between; life is a process. Raj Ayyar: You seem to be a gay Buddhist or at any rate a simpatico fellow traveler. How has Buddhism impacted your life and work?

Raj Ayyar: The character of Vince in Through It Came.. is a heady mix of junkie, kleptomaniac, Buddhist philosopher and abused child. Yet, he never seems to emerge from his own Shadow zone to reach the 'bright colors.' Any comments? Trebor Healey: We can't judge anyone else's path. I'm not sure Vince is even interested in redemption. He's a kind of messenger. In other words, Vince doesn't conform to Neill's dreams for him, but Vince actually teaches Neill more by not doing so. We have no way of knowing what is right for someone else and if their goals are anything like our own. And why should they be? The bright colors still come through. Vince is a window for Neill, a window of brilliant things. We don't know where he goes in the end, so the verdict remains out on him. He's most interesting as a question, and he is bright because he lives as a question. Raj Ayyar: Neill Culane's coming out is a complex, not so happy process. But at the end of the novel, I was left with a definite sense that Neill has grown spiritually and emotionally from his stormy relationship with Vince, not to mention the caretaking of his cancer-ridden brother Peter. Is the novel cautiously optimistic about Neill's future? Trebor Healey: Yes, you could say that. Neill has been honest and listened with his whole heart. I think he is respectful of what is happening and this is a good thing for anyone; a promising thing. Neill has become wiser and better able to love. Raj Ayyar: Readers used to the steamy eroticism of some of your earlier work might find 'Through It Came..' an almost asexual novel framed painfully against the backdrop of cancer. Is there a reason for the shift in style and content? Trebor Healey: Yes, and a lot of people have asked me about that. I write a lot of ecstatic erotic and sexual poetry, but in this story I wanted to focus on a fuller kind of eroticism, and perhaps a more difficult and intimate one. I mean the eroticism of physical reality itself-not just of bodies and lovers, but through the body of the ill beloved, through the trees, the sidewalks, the weather, and through the erotic physicality among family members. I think eroticism is everywhere-it's how mammals relate and perceive-and sex is just one way it manifests. So I wouldn't say the story is 'asexual'. A lot of the sexual scenes between Vince and Neill are messy and problematic because they are about very real vulnerability and very real intimacy. I think that's actually sexier. Raj Ayyar: Cancer, rather than AIDS, dominates the landscape of Through It Came.. Neill's brother, the beautiful, athletic Peter has a tragically disfiguring cancer, while Vince has testicular cancer. Did you want to move away from the past two decades of the gay AIDS novel?

Trebor Healey: Well, the Buddha calls this world samsara. And samsara is a realm of suffering; an imperfect world, under the sway of desire and aversion. I love the world, but if I'm completely honest with myself, I can't romanticize it. Nor would I romanticize or idealize a character. I think romanticization really betrays people. It's a promise that no one can keep. Life is tough; it ain't gonna work out. And that's OK. Learning to be OK with how fucked-up the world is, while at the same time staying engaged to try to better it in whatever way you can is all we really have. The Tenderloin is a terrible place, and it does no one a service to sugarcoat it. But if you're looking for wise people, they do exist in the underworld because they are living in a raw way which teaches you a lot of things. Raj Ayyar: I loved the Ojibwa saying that prefaces the book: "Sometimes I go about pitying myself when all the time I'm carried on great wings across the sky." Can you explain the context of the saying? Trebor Healey: Well, it's all about Neill's tragic attitude that gets dismantled by what happens in the book. If you just stick with things, pay attention, try to keep your heart open, there are rewards. They may not be what you wanted, but they're real and true and what is and they challenge you to a greater consciousness. Those are the wings we are all trying to grow. Tom Spanbauer, in The Man Who Fell in Love with the Moon, illustrates this so beautifully when he says something like: the story you are telling yourself is not really the story at all. We all get caught up in our own ego stories. Raj Ayyar: You have been quoted as saying that Los Angeles has been very good to you. Are you planning to write a novel set in LA? Trebor Healey: Interesting you should ask. My next novel will end up there. I like LA because of its nothingness. It's the great Buddhist city in a sense: you can project anything on to it, but nothing really sticks. Some people hate LA's lack of personality or blankness; its lack of a center. I find it really interesting and liberating. Raj Ayyar: Through It Came.. gets away from the coming out novel's tendency to demonize the straight family. Neill's parents are pretty cool and Peter is more than an understanding sibling buddy in his total acceptance of Neill's sexuality. True, there's the shadowy (but mercifully absent) brute Paul but, on the whole, Neill has a relatively easy coming out passage. Do you think there's a new, more accepting pattern emerging in many metropolitan families now? That gayness may be accepted by many with a shrug if not a hug? Trebor Healey: Well, let's hope so. But let's get back to 'cautious optimism'. We have a long way to go. I think it's important not to become complacent. The Religious Right in this country is virulent. I think there is social progress, but I grew up during Vietnam and I thought we had learned not to ever do that kind of thing again. And now look. Neill was very lucky, and part of why I wanted him to be lucky in this regard was that he was so sure he was unlucky. Neill, of course, benefited from his family being completely torn down emotionally, facing the loss of a young son. Through it, they got their priorities straight-as people who go through hell do. They reached an understanding about love as acceptance. People who haven't been through a lot, who are afraid and ignorant, can be very stingy and controlling about love. Which really isn't love at all, is it? Coming out is about love, and I think family members who don't handle it well, or miss that, need to look very hard at themselves and their values. Raj Ayyar: Did the Beat poets and writers influence you at all? There's a scene in the novel where Neill launches into a "glowing discourse" about Kerouac's Dharma Bums. Vince shoots down Kerouac, describing Dharma Bums as "sloppy tortured Catholic bullshit." Is that your view of Kerouac as well? Trebor Healey: Oh, that! You know I used to have dreams about Jack Kerouac as my father. He meant a great deal to me at one time and I still think his work is very important. I read all his books. I admired his ability to write from his heart, and express the clumsiness of human life. His heroes are all so human and flawed. And he's a great poet of prose, and he taught me how to do that. But he never overcame his demons of alcoholism and being queer, and they made him a tragic character. I'd never judge him for that though. I feel fortunate that I was born many decades later because before I came out, when I was reading his books, I really was full of sloppy tortured catholic bullshit. I'm kind of needling myself with that line more than him. But we had much in common in terms of how he grew up, etc. He also was the person who first turned me on to exploring Buddhism. Like I say, he's a daddy for me. Raj Ayyar: Are you working on a new creative project---a novel, a short story or whatever? Can you tell our readers a little about it? Trebor Healey: I'm working on a novel. It's a road novel about a sort of screwed-up San Francisco queer Huck Finn who finds his Jim in a Native American medicine man while he's riding his bike cross-country with his lover's ashes tied to the handlebars. You see, the ghost of Kerouac haunts me still. Raj Ayyar: Is there anything else that you would like to share with readers of Gay Today? Trebor Healey: "Tis a gift to be gay" in the immortal words of Harry Hay. I'm grateful for it every day. It can grow your wings. I hope my book helps people to do just that. Raj Ayyar: Thank you, Trebor. I've enjoyed interviewing you. Trebor Healey: Thank you, Raj! |

|

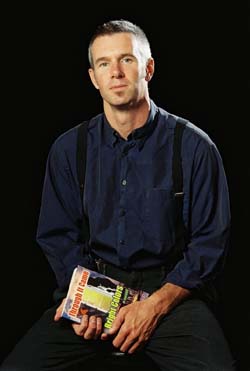

Trebor Healey is the author of Through It Came Bright Colors

Trebor Healey is the author of Through It Came Bright Colors Trebor Healey: Profoundly. I was sick as a young adult, and I was suicidal with despair about my physical and emotional problems. I was a nihilist, which is where you end up if you honestly inquire into western culture, in my opinion. But there is possibility even in nihilism and existentialism. And I think that is what Buddhism is, and what it offered me, at least in its higher forms. I came to it through Yoga actually, after I'd given up on western medicine. I had lost hope, and Buddhism offered ideas like: if you've lost hope, you can finally start to see what's really there. You don't have to fight everything or believe anything -- just pay attention, accept what is in front of you as a teaching, try to understand and bring your heart into your hell. It was interesting. And it kind of broke my heart. On some level, I felt the Buddha was this androgynous sort of dude who was laughing at how serious and personal I was taking things. The Buddha is kind of a big drag queen. The key teaching, I think, is not to take anything personally and to have no expectations. That's like a huge flower that bloomed for me. It was like coming out. Liberation.

Trebor Healey: Profoundly. I was sick as a young adult, and I was suicidal with despair about my physical and emotional problems. I was a nihilist, which is where you end up if you honestly inquire into western culture, in my opinion. But there is possibility even in nihilism and existentialism. And I think that is what Buddhism is, and what it offered me, at least in its higher forms. I came to it through Yoga actually, after I'd given up on western medicine. I had lost hope, and Buddhism offered ideas like: if you've lost hope, you can finally start to see what's really there. You don't have to fight everything or believe anything -- just pay attention, accept what is in front of you as a teaching, try to understand and bring your heart into your hell. It was interesting. And it kind of broke my heart. On some level, I felt the Buddha was this androgynous sort of dude who was laughing at how serious and personal I was taking things. The Buddha is kind of a big drag queen. The key teaching, I think, is not to take anything personally and to have no expectations. That's like a huge flower that bloomed for me. It was like coming out. Liberation.

Trebor Healey on Through It Came Bright Colors: I feel like I almost wrote an AIDS novel without AIDS.

Trebor Healey on Through It Came Bright Colors: I feel like I almost wrote an AIDS novel without AIDS.