|

|

|

|

The Book Nook |

|

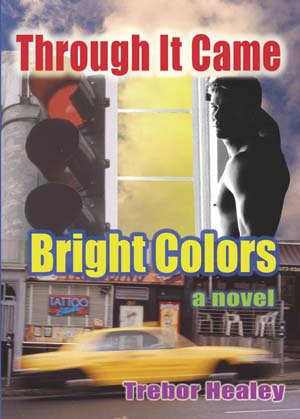

Through It Came Bright Colors by Trebor Healey; Harrington-Park Press; 2003; soft-cover $19.95, hardcover, $34.95

We two boys together clinging,

one the other never leaving,

up and down the roads going...

eating, drinking, sleeping, loving.

Part of the novel's avoidance of the cliches of coming out lies in the fact that, though Neill wrestles with the demons of his internalized homophobia, there isn't the bad faith attempt to distance himself cognitively and emotionally from his sexuality by denying it. Driving through San Francisco on "one of those few and far between beach weather days", (one of those dutiful family values picnics), his dad puts on his 'joker's face' and says to his young sons in the back seat, "Look, boys--look at the fag over there with the poodle", pointing to a "man in a blue pantsuit with a bouffant hairdo, leading a little groomed white poodle on a leash." This is the 11-year old Neill's first exposure to Polk Street, San Francisco and to the searing knowledge that he and the man in the blue pantsuit "were one and the same in fate." His mother tries to soothe him by telling him that it was okay, that the man couldn't hurt him. Neill's inner comment is poignantly self-aware: "He is inside me, Mother; he can hurt me." A central axis of the novel is the tortured relationship between Neill and his shadow-driven lover Vince Malone. Vince is a junkie, a cancer patient, a street philosopher, a hustler, thief and part-time Buddhist, living in a decaying Tenderloin hotel. Vince is a dark retro-parody of a character out of a '50's Beat novel, the brave new on-the-road idealism and whoopee enthusiasm of the Beat poets replaced by bitter rage. It is a measure of Neill's great strength that he not only survives the stormy, up and down relationship with Vince, he emerges from it wiser and more centered in his gay identity. Pioneering Jungian gay psychologist Mitch Walker has argued that same-sex relationships are characterized by the archetype of the Double, "a soul figure with all the erotic and spiritual significance attached to the anima/animus (the inner female and male in the psyche), yet not the Shadow (the dark side of the psyche). The Double embodies the spirit of love between those of the same sex and fuses the fate of two into one." (Quoted in Mark Thompson: Gay Body: A Journey Through Shadow to Self. NY: St. Martin's Press, 1997). Thus, while heterosexual relationships involve the exploration of the Other who is different from me, same-sex relationships can be rich explorations of the archetype of the Same, of the mirrored 'I' in the same-sex partner.The Double is exemplified in many mythic and fictive same-sex couples: David and Jonathan, Ruth and Naomi, Gilgamesh and Enkidu, Sherlock Holmes and Watson, to name a few.

"But I did turn before leaving, remembering how in (Kerouac's) Dharma Bums, Gary Snyder always thanked and blessed his campsites before he left them. How should I do so now? I wondered...remembering Vince's lama. I tried that, but I was a Catholic boy, so I genuflected and crossed myself and wishing Vince all the best, leaving him there in that time and place, enshrined forever. Our Lady of thievery and junk--and fine cooking, and bitter irony and cruel, snippy comments....patron saint of all the fucked in the world." The other major axis of the novel is the narrator's tender relationship with his straight brother Peter. A former high school jock, now dying of cancer, he totally accepts Neill's sexual orientation. In many ways, he is Neill's real 'Double.' Their relationship has none of the shadowy sturm und drang, none of the roller coaster ride dynamics of Neill's affair with Vince. The novel is haunted by the sadness of Peter's slow dying process, Yet, the somberness of the cancer frame--Vince and Peter both have it---puts the coming-out process in perspective. Certainly, there's awkwardness and pathos in Neill's fumbling attempts to come out to his parents. But the enormity of the cancer landscape takes the melodrama out of the coming-out process, such that both his parents come to terms with his gayness rather quickly. Twisting Whitman's lines just a little, Neill and Peter are 'two brothers together clinging', and even after Peter dies, "ancient and earth now", Neill has this intense visualization of backpacking with Peter in Yosemite. There are no happy endings for Neill, just a maturation colored by sadness and compassion. Maybe that is what life is about: surviving one's own valley of the shadow and emerging, not unscarred, but with a deeper, fuller sense of who one is. |

|

Trebor Healey's first novel Through It Came Bright Colors escapes the cliched boxes of the coming-out novel. It successfully avoids kitsch, while presenting a gay rite of passage with a fine fusion of tenderness and toughness. The central protagonist, Neill Culane, is a closeted 21 year old who "felt like a blank sheet of paper in need of a story." Neill has known that he's gay since he was about 11 years old.

Trebor Healey's first novel Through It Came Bright Colors escapes the cliched boxes of the coming-out novel. It successfully avoids kitsch, while presenting a gay rite of passage with a fine fusion of tenderness and toughness. The central protagonist, Neill Culane, is a closeted 21 year old who "felt like a blank sheet of paper in need of a story." Neill has known that he's gay since he was about 11 years old.

Author Trebor Healey

Author Trebor Healey